LONDON • Few topics remain off limits in United States presidential elections. But the fate of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato), the US-led military alliance which has provided security in Europe since the end of World War II, was one such rare taboo: No presidential candidate from either mainstream party has either questioned the reason for the alliance's continued existence or America's enduring commitment to Nato in any of the 16 presidential elections which have taken place in the US since 1952.

No longer, however, since Republican candidate Donald Trump has now broken the taboo, by dismissing Nato as largely irrelevant for US security concerns and by threatening that, should he be elected, he may be tempted not to honour America's security guarantee to European allies.

Mr Trump's apparent rejection of one of the cornerstone institutions of global security has stunned US partners in Europe. For although the Republican candidate's attitude to Nato may be boorishly ill-informed, the doubts he voiced about America's system of overseas alliances are shared by the US voting public and, if not addressed squarely, may end up affecting America's security posture not only towards Europe, but also in the world at large.

Since Nato was founded in 1949, the Europeans never paid their full share of the organisation's expenses. Initially, all American planners accepted that Washington would have to provide the bulk of the cash and military assets to the alliance, partly because Europe was destroyed by war and therefore incapable of looking after its own security, and partly because Europe faced an existential threat of millions of Soviet soldiers, and the very purpose of the alliance was to harness American might against them.

As European economies completed their post-war recovery during the 1960s and Europe even began to rival the United States in terms of overall wealth, successive generations of American politicians tried to persuade the Europeans to contribute more to their own defence, but to no avail. By the early 1990s when the Cold War ended, the US alone paid for half of Nato's military capabilities, a situation which American leaders resented yet failed to change.

Since then, matters only got worse: The Americans are now responsible for no less than 80 per cent of Nato assets, despite the fact that in terms of population and combined size of their economies, the Europeans are actually bigger than the US. And efforts to shame the Europeans into spending more, such as that by then US Defence Secretary Robert Gates, who at the beginning of this decade publicly warned that Nato faces a "dismal future" of "collective military irrelevance" unless its European members increased their financial contributions, led nowhere.

So did the pledge which European governments made to devote at least 2 per cent of their gross domestic product to defence each year: Out of the alliance's 28 member states, only five - the US, Britain, France, Estonia and Turkey - are honouring this promise while Germany, Europe's biggest and wealthiest European nation, spends precisely 1.2 per cent of its GDP on the military at the moment. Seen from this perspective, Mr Trump appears to have a point when he suggests that the US should defend European Nato members only if Washington is "reasonably reimbursed" for the "tremendous cost" of protecting Europe.

WHAT NATO MEANS FOR AMERICA

But seeing the alliance with Europe as a purely commercial transaction is a big mistake. For although considerable, the US contribution to Nato is not that massive, while the strategic benefits which America derives from Nato are much bigger than commonly understood.

Most ordinary Americans live under the misperception that the troops they have deployed in Europe are permanently allocated to defending that continent, and therefore represent a loss to US military commanders elsewhere in the world; Mr Trump himself resorted to this explanation during the current electoral campaign, when he complained that Nato detracts from America's ability to deal with its own, "real security concerns".

This is false, since the American troops deployed in Europe - whose numbers have been falling precipitously during the past two decades - are also available to US presidents for operations else- where; all the wars and deploy- ments which the US conducted in the Middle East since 1990 involved substantial numbers of US troops from Europe and, incidentally, also a substantial use of European bases for logistical support, as well as the treatment of wounded US soldiers from these conflicts.

So, far from detracting from US military power, Europe acts as a massive launch pad which enhances US power projection across the world's Northern Hemisphere, extending from the North Pole through the entire Atlantic Ocean region and most of Africa and the Middle East.

Nor do the Americans squander their military cash in Europe. According to calculations compiled by Rand, one of the biggest US think-tanks, Washington spends around US$10 billion (S$13.6 billion) each year to keep American troops in Europe. But at least half of that is paid back by European host nations, so the total bill to the US taxpayer amounts to about 1 per cent of America's defence budget, hardly the "tremendous cost" of Mr Trump's imagination.

But what the US gets from Nato in return is genuinely tremendous. It runs the biggest military alliance the world has ever seen, one which dwarfs all of America's potential opponents combined. As every American president discovers upon stepping into the White House, Nato gives Washington an automatic leadership over a part of the world which accounts for over half of the world's wealth and two-thirds of scientific innovation.

Nato allies also contribute in different other ways to US security objectives. They spend far more on foreign aid and refugee resettlement than the US does. They contribute far more to United Nations peacekeeping operations. European militaries stuck for 15 years in Afghanistan and suffered more than 1,000 casualties, not because they necessarily believed in that war or were consulted in its pursuit, but because, as Mrs Dalia Grybauskaite, the feisty president of tiny Lithuania once put it, "we believe that America's security concerns are our own". Trying to explain to an American mother why her son died in Afghanistan is hard, but trying to explain the same loss to the bereaved parents of a Romanian or a Polish soldier is even harder. Yet this was done without as much as a single protest by most of Nato's European nations.

The only time Nato's mutual security guarantee contained in the famed Article 5 of the alliance's founding treaty was invoked was on Sept 10, 2001, a day after America suffered its 9/11 massive terrorist attack. And when that happened, there was not a single murmur of dissent from a European capital. None of these contributions are included in the cold figures of defence budgets. But all are the priceless assets of an alliance which America's rivals such as China or Russia have no chance of replicating.

Besides, one needs to think of the alternative, should the US decide that Nato no longer serves its purpose. The outcome will be a collapse of all European security arrangements, and more rather than less tension with Russia, for the Russians will be encouraged to test European defences to the limit. China may be equally tempted to test US resolve in Asia, for it is fanciful to believe that the US could wash its hands of Europe but still retain its credibility in Asia.

It could be argued that current efforts by France and Germany to establish separate military headquarters for European armies outside Nato amount to an attempt to address US concerns about European contributions to their own security. But in reality, they are nothing of the kind, for the Franco-German initiative is merely a classic example of a solution in search of a problem: Europe has no need for new military headquarters, and nobody knows what to do with them. In fact, the entire Franco-German effort is only being undertaken in order to show the world that despite Britain's decision to leave the European Union, the Europeans are determined to continue with their integration; the initiative is, therefore, not a military but a political project with no military applications.

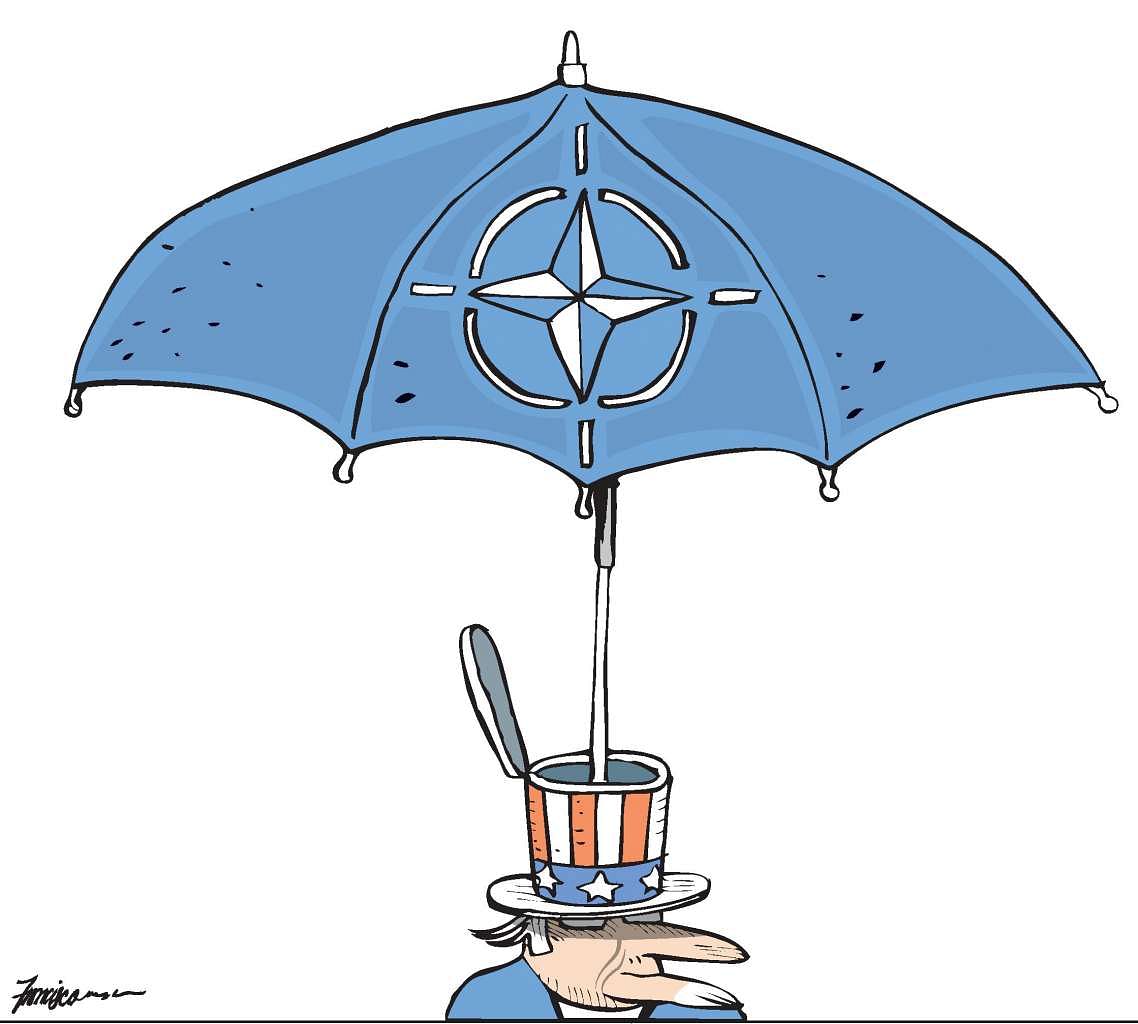

The truth remains that, for the foreseeable future, Europe cannot do without America's protective military umbrella, and the US is well-advised to continue enjoying Nato's backing. The relationship is neither equitable nor ideal, yet it is one which worked for decades, costs little in practice and can continue working into the future.

This is a simple argument which Mr Trump has failed to grasp but which, luckily, is still shared by most other decision-makers in Washington.