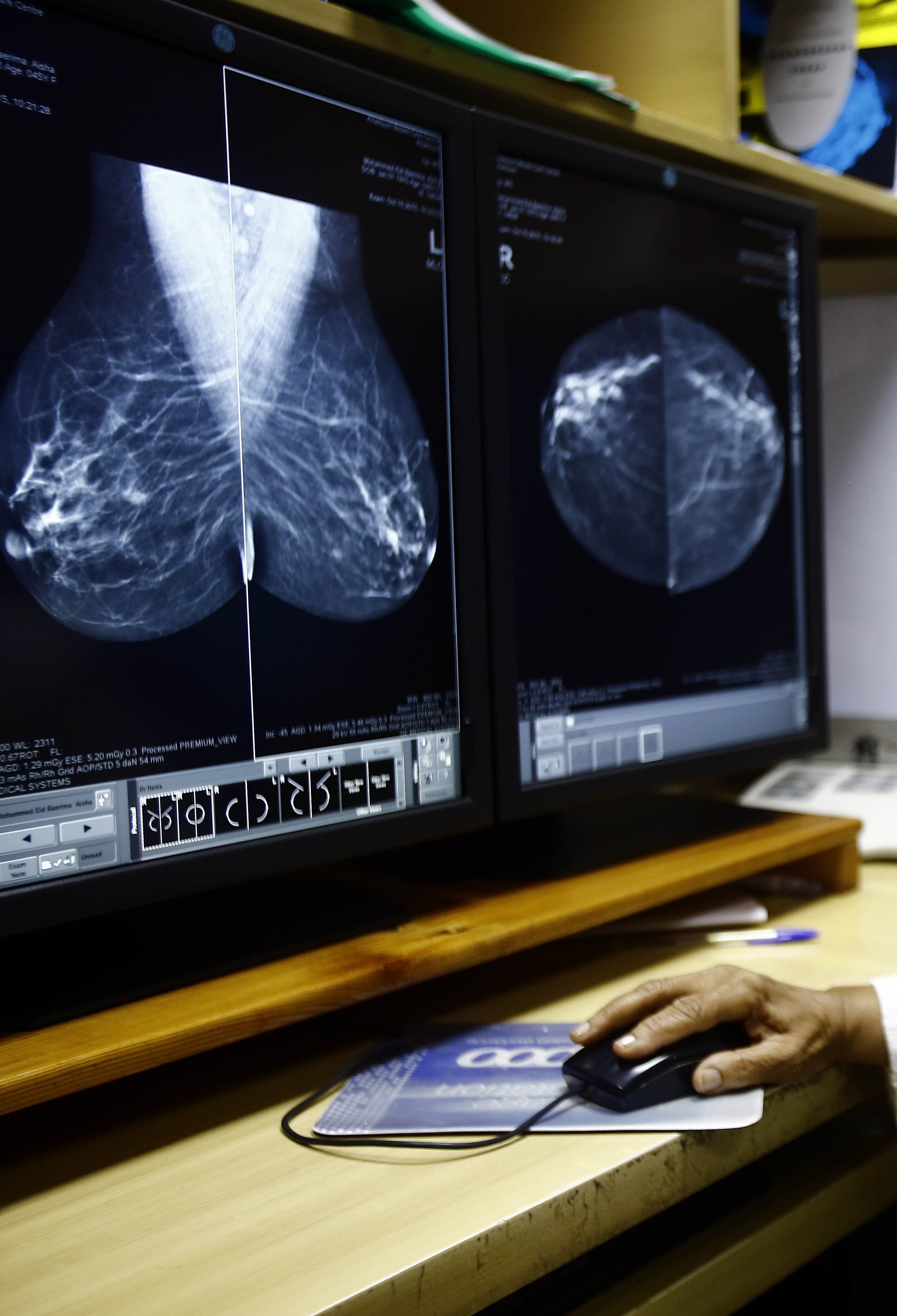

Last week, the American Cancer Society announced changes to its influential guidelines for breast cancer screening. The society no longer recommends that women at average risk between the ages of 40 and 44 have mammograms and advises reducing the frequency of mammograms from every year to every other year for women 55 and older. The group is also recommending ending physical breast examinations by doctors entirely.

We profoundly disagree with these changes. All three of us, two breast radiologists and one breast surgeon, have been named "Mothers of the Year" by the American Cancer Society in recognition of our roles as mothers and physicians who have devoted our professional lives to the fight against breast cancer. One of us, Drossman, received her award the day before the new guidelines were issued.

Because of our shared goals - early detection of breast cancer, improved treatments and saving lives - we were happy to support the cancer society. Now, we no longer wish to be involved.

Despite the changes, the society's website still states: "The American Cancer Society breast cancer screening guidelines are developed to save lives by finding breast cancer early, when treatment is more likely to be successful." Mammography in all age groups, starting at 40 years old, is the only test that has been proven to do exactly this: reduce the risk of dying from breast cancer, by up to 30 per cent.

Today, the overall survival rate for breast cancer in the United States is very close to 90 per cent, the highest it has ever been, giving most newly diagnosed patients every reason to be optimistic. Early detection with mammography and better treatment options are both directly responsible for that.

It's not just a matter of saving lives. There are other almost equally important benefits of early detection by mammography. For example, women with cancers detected at smaller sizes are much more likely to be able to have a lumpectomy and less aggressive, less disfiguring surgery. In addition, the smaller the cancer, the lower the likelihood that the disease may have spread to lymph nodes and elsewhere. In turn, this means there is less likelihood of needing aggressive treatment after surgery like chemotherapy and radiation.

A further problem with the new guidelines is that increasing the interval between screenings for women over the age of 55 will result in delayed diagnosis and larger tumour sizes. This will lead to more extensive and potentially expensive treatment.

We all agree that mammograms are not perfect; there is no ideal test for detecting any kind of cancer. False positives are a reality for screening tests of all kinds. Let's stop overemphasising the "harms" related to mammogram callbacks and biopsies.

In breast cancer screening, most false positives - when a mammogram suggests something that requires further investigation - are easily resolved with additional images that put the concern to rest. Only 2 per cent of screening cases cannot be resolved by further imaging and require a biopsy.

In our collective experience of 60 years, none of us has ever seen a potentially life-threatening complication related to a breast biopsy. The same cannot be said for other tests, such as colonoscopy, where there is a risk of perforation, which can lead to emergency surgery, and even death. Even computerised tomography, or a CT scan, can be associated with allergic reactions to the injected contrast dye. In the most severe cases, these can lead to life-threatening anaphylaxis.

To be sure, breast biopsies can be temporarily painful, but when performed by experienced breast radiologists, the procedure is almost always minimally invasive, requiring only local anaesthesia. Research has shown that even women who experience false positive results remain enthusiastic about continuing their screening and accept this as a reasonable price for early detection.

In the week since the cancer society issued the new guidelines, we have all encountered patients who said they were grateful that they'd benefited from early detection of breast cancer by mammography. Many expressed concern that their diagnoses would have been delayed under the new guidelines.

In our experience, the anxiety caused by being called back for further imaging or a biopsy is modest compared with the stress of treatment for a late-stage breast cancer that might have been detected earlier.

A 2014 study that followed more than 7,000 Massachusetts breast cancer patients demonstrated that, sadly, of all the women who died of breast cancer, 65 per cent had never had a mammogram and 6 per cent hadn't had one in the preceding two years.

Finally, we think it's noteworthy that while there were medical specialists involved in an advisory group, the panel actually charged with developing the new guidelines did not include a single surgeon, radiologist or medical oncologist who specialises in the care and treatment of breast cancer.

Not one.

We understand that the rationale for this may have been to prevent bias in interpreting the data. At the same time, we observe that in a panel that included an economist and public health experts, there was potential for bias the other way - in favour of cutting costs over saving lives.

We know there are pressures to reduce healthcare costs in the United States, and that health spending cannot be a bottomless pit. But those who will suffer most from these cancer society recommendations will be women from underserved communities who do not have the means to pay for their own breast cancer screening if insurers follow the new guidelines and stop providing yearly coverage to women over 40. The fair thing would have been to include in the conversation some of us who are in the front line of diagnosing and treating this disease.

The new guidelines were presumably intended to balance the known benefits of mammograms with the potential harms, and to spread the costs and benefits intelligently by age group. In reality, these new recommendations have created more confusion than clarity.

Our goals remain clear: to detect breast cancer as early as possible and reduce the risk of dying from this disease. We and our many colleagues who are intimately involved in patient care will continue to recommend to women annual screening mammograms starting at age 40.

NEW YORK TIMES

- Susan Drossman is a breast radiologist in private practice in New York City. Elisa Port is chief of breast surgery and Emily Sonnenblick is a breast radiologist at the Dubin Breast Centre at Mount Sinai Hospital.