First came the 2008 financial crisis. Then, many years of tepid economic growth.

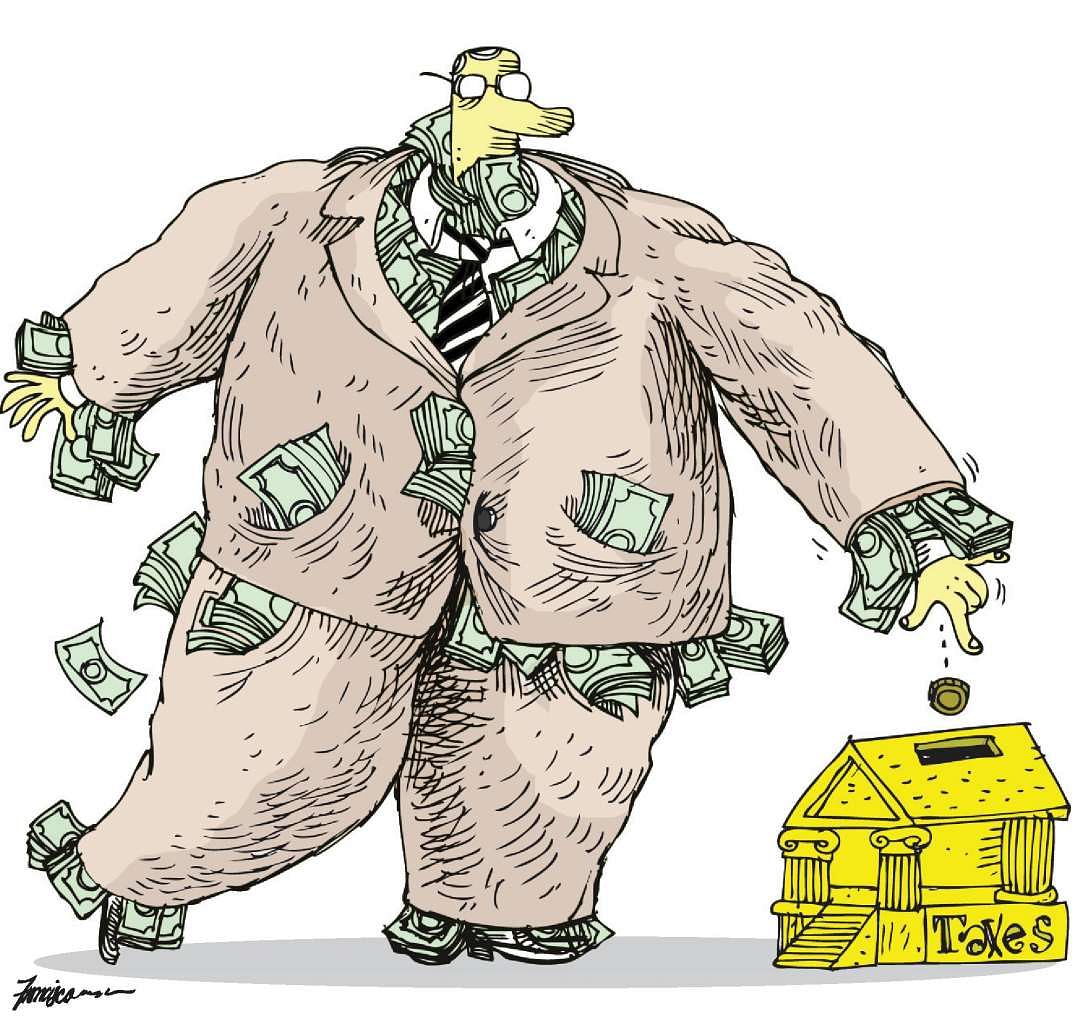

Around the world, government coffers are running dry.

No wonder, then, that taxmen from Europe to Indonesia are on the hunt for money that they believe is owed to them, especially by big corporations.

Authorities around the world are battling it out with corporate giants to claw back whatever tax revenues they can, making dramatic headlines - Apple vs the European Union, Google vs Indonesia, Starbucks vs Britain.

Singapore, with its 17 per cent corporate income tax rate - among the lowest in the world - has on occasion been placed under a less-than-flattering spotlight as a result, with some foreign regulators accusing companies of shady accounting practices so that they can book profits and pay taxes here, avoiding higher tax rates elsewhere.

But in fact Singapore has joined up with the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to implement and promote measures to combat corporate tax avoidance.

Furthermore, the competitive tax rate here is but one of many factors that have led to Singapore repeatedly being named one of the best places in the world to do business, consultants told The Straits Times.

Still, in this new climate, scrutiny of corporate tax is set to intensify. How is Singapore gearing up, and what will it mean for the economy and local corporations?

BASE EROSION AND PROFIT SHIFTING

Many of the battles being waged between tax authorities and multinationals centre on a practice known in accounting jargon as "base erosion and profit shifting" (BEPS).

To illustrate it simply: Say Corporation X, a multinational with businesses all over the world, has mega factories in the United States where it hires hundreds of workers to produce its goods, which it then sells for healthy profits.

Rightfully, Corporation X should pay a certain amount of income tax to the US government each year.

However, it could make use of creative accounting techniques to "shift" its profits elsewhere.

So instead of booking those profits in the US, it may claim that its profits were actually made elsewhere - say, in Ireland, where the corporate income tax rate is 12.5 per cent, much lower than the 35 per cent federal corporate tax rate levied in the US.

And so in recent years, the OECD and the Group of 20 developed economies (G-20) have embarked on a BEPS Project which aims to get tax authorities around the world to set standards that will help clamp down on BEPS.

Singapore has signed on to this project as a "BEPS Associate" and has been providing input to the project since 2013.

The Ministry of Finance (MOF) has made clear that Singapore supports the BEPS Project principle that profits should be taxed where activities giving rise to the profits are performed and where value is created, and it does not condone the artificial shifting of profits.

"Businesses locate their substantive functions in Singapore to pursue regional and global strategic interests, including establishing Centres of Excellence in Singapore for training and development, research and innovation, mid-office functions such as compliance, risk management and technology," the MOF said in a statement.

"They conduct these substantive functions here due to a variety of factors, including our location at the heart of Asia, our good infrastructure, a transparent and robust legal and regulatory regime, and a skilled labour force."

Notwithstanding the Government's vocal support of the BEPS Project and its active participation in it, Singapore has been cited in some cases of disputes over tax avoidance.

In one ongoing case, the Indonesian government has accused Google of not paying proper taxes for the past five years, and it has even gone as far as raiding Google's office in Jakarta to collect data on its advertising revenue in the country.

Google, in response, has said that it has paid all applicable taxes in Indonesia, where the corporate tax rate is 25 per cent, and that its local entity does not handle advertising revenues. It claims ad incomes are booked in Singapore, where Google has its Asia-Pacific headquarters.

Australian tax authorities have also been probing companies operating Down Under which it accuses of shifting billions of dollars of profits to Singapore.

In the meantime, outside of the BEPS Project, countries around the world are clamping down on tax avoidance in their own ways.

The European Commission(EC), for example, has recently made headlines for ordering Apple to pay a record €13 billion (S$19.9 billion)in back taxes to Ireland.

The EC, the executive arm of the European Union(EU), said a tax deal between Irish regulators and Apple amounted to state aid that was illegal under EU laws, which prohibit member states from giving tax benefits to selected companies.

THE IMPLICATIONS FOR SINGAPORE

These developments point to an overall climate of greater scrutiny on tax issues all around the world.

Singapore cannot escape the spotlight, and indeed, by signing up to the BEPS Project, Singapore's tax incentives scheme will come under review to determine whether any are "harmful", noted Mr Steve Towers, the Asia-Pacific leader of international tax for Deloitte & Touche.

"A tax incentive will be considered to be 'harmful' to the extent that it provides a lower effective tax rate for income derived by a taxpayer, even though the taxpayer did not itself perform the substantive activities which gave rise to the income," he explained.

That is, the incentive is rewarding the company for shifting its profits to a lower-tax jurisdiction.

According to Mr Towers, one example of a "harmful" tax incentive by OECD standards relates to the exploitation of patents.

"If the relevant research and development (R&D) is performed by a related party, or if the patent is licensed to the taxpayer, or if the taxpayer has purchased the patent, a tax incentive given to the patent income will be considered to be 'harmful'," he said.

"In contrast, the tax incentive will not be harmful if the patent was the result of R&D performed by the taxpayer only."

So a company can only be given a tax break on a patent if it had conducted the R&D resulting in the patent itself, and not if the R&D were done by a partner company or a different subsidiary within a larger group of companies.

While some of Singapore's existing tax incentives are likely to be deemed fully compliant with the BEPS principles, there is a real chance that some will need to be amended, he said.

What is unlikely, he added, is that Singapore will lose its edge as a great place to do business - an opinion shared by other experts.

"If you ask a company, 'Do you invest in Singapore because of tax?', almost 100 per cent would say no. I say this from experience," said PwC Singapore tax leader Chris Woo.

"I was with a client yesterday who is coming here for business reasons - Singapore is a great gateway to the Asian market - and for lifestyle reasons, Singapore being a great place to live, that is safe for his kids and has the rule of law."

Meanwhile, Singapore should also make it clear to the world that it does not tolerate tax avoidance or profit shifting, noted Mr Henry Syrett, a partner focusing on transfer pricing services at Ernst & Young Solutions.

Indeed, he said, the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (Iras) seems to have ramped up its resources and is scrutinising tax returns more closely, and his team has been receiving more questions from Iras related to transfer pricing.

Transfer pricing is an accounting term referring to the practice of one unit within a larger group of companies selling a good or service to another unit within the same group.

By law, these units should complete that transaction based on market prices. However, some multinationals have been caught abusing this, for example by inflating the price of these transactions as a way to shift profits from a unit in one country to a unit in another country with lower taxes.

"Iras may look at a company's accounts or tax returns and see an item on related party transactions and it will ask what's the basis for that price, so they know the company hasn't under- or overstated that price to transfer funds where it shouldn't be," Mr Syrett said.

THE IMPLICATION FOR CORPORATIONS

Another big change coming up as part of the BEPS Project is the implementation of Country-by-Country Reporting (CbCR).

When CbCR takes effect, multinational companies will have to prepare a report setting out key data for all countries in which they operate, such as revenue, pretax profits, taxes paid and employee numbers.

That report will be distributed to the tax authorities in all the countries in which the group operates.

Each tax regulator can then see whether they have been paid the proper amount of tax. Did the company make more revenue in India and hire more employees there, yet pay most of its taxes in Hong Kong?

This is the sort of scrutiny companies can expect when CbCR comes into effect, said Mr Woo, and it will have major implications for Singapore firms that are being encouraged to venture abroad.

"We need to help our local firms - are they equipped to deal with issues like that? Singapore is a big service economy. As our digital industry expands, that will also attract more attention from tax regulators around the world."

Much of the work in ironing out such issues will involve regulators communicating with each other and agreeing on treaties that will prevent companies from being doubly taxed on the same pot of income.

But companies will have to do more tax planning too, Mr Woo said.

"They must have a better understanding of tax issues and be aware of these minefields. Everyone is busy trying to find their dollar of revenue and some companies say they don't have time to think about tax, but you need to find the right balance."