The ongoing rivalry between the United States and China in Asia took a surprising turn when Britain decided last week to join the China-backed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as a founding member. This was by no means a trivial matter. What could be at stake is no less than America's decades-long leadership in Asia, as China woos not only its immediate neighbours, but also leading Western powers.

In an interview with the Financial Times, an American official bluntly expressed his country's dismay with Britain's decision, stating how Washington was "wary about a trend towards constant accommodation of China, which is not the best way to engage a rising power".

For months, the US reportedly lobbied its allies against joining the AIIB, placing a de facto embargo on the new institution.

Officially, the US maintained that the China-backed financial institution did not meet globally accepted standards embodied by existing Bretton Woods institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

The US National Security Council, in a statement to The Guardian newspaper, expressed Washington's "concerns about whether the AIIB will meet these high standards, particularly related to governance, and environmental and social safeguards".

Joining the AIIB, Washington argued, would undermine the existing architecture of global governance. Therefore, the importance to see the "AIIB complement the existing architecture, and work effectively alongside the World Bank and Asian Development Bank".

The emerging consensus among experts, however, pointed at Washington's growing worry over the prospect of China's emergence as the pre-eminent power in the Asia-Pacific theatre - at the expense of the US.

Britain tried to justify its decision by underlining the importance of maintaining a strong presence in the emerging institutions of governance in Asia, which had become an increasingly important trade and investment partner to London. As a founding member, London argued, Britain would be in a better position to ensure maximum transparency, efficiency and accountability in the design and operation of the AIIB.

Britain was most likely more concerned with maintaining London's edge (over competitors like Frankfurt) as the preferred destination for Chinese businesses and investments in Europe.

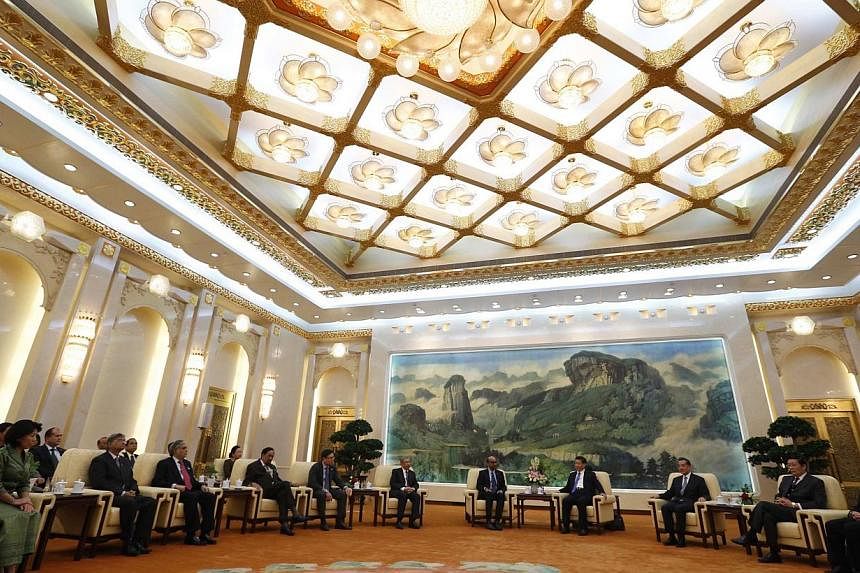

Traditionally, Germany and France had been at the forefront of Europe-China economic relations. But since British Prime Minister David Cameron's late-2013 visit to China, London had doubled down on its efforts to expand trade and investment ties with the Asian powerhouse.

American treaty allies such as the Philippines and New Zealand, as well as strategic partners such as India, Indonesia and Singapore, are already among the AIIB's founding members.

There are growing signs that the US-led boycott of the AIIB is falling apart. France, Germany and Italy are following in Britain's footsteps, as European powers scramble for access to Asian markets - and China's favour.

With some 30 countries signing up, the AIIB has become significantly diverse, multilateral and representative in its composition.

No wonder, America's top strategic partners in Asia, specifically Australia, South Korea and Japan, are also reconsidering their initial boycott.

China presented the AIIB as a much-needed institutional remedy to the US$8 trillion (S$11 trillion) financing gap for Asia's rapidly expanding infrastructure needs. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China has emphasised the deepening of influence in its peripheries by maintaining economically robust ties with neighbouring countries.

In his late-2013 speech on the importance of peripheral diplomacy, Mr Xi signalled China's intent to "comprehensively develop relationships" and "solidify economic bond" with neighbouring countries.

The Asian powerhouse is no longer confined to Deng Xiaoping's age-old dictum that China should maintain a low profile in international affairs, focusing on economic development through robust ties with Western countries. With China emerging as a global economic force, Mr Xi is determined to assert Beijing's leadership in the region.

"The policy now is to allow... smaller countries to benefit economically from their relationships with China. For China, we need good relationships more urgently than we need economic development," Mr Yan Xuetong, a prominent Chinese scholar at the prestigious Tsinghua University, said in a recent interview. "We let them benefit economically and, in return, we get good political relationships. We should 'purchase' the relationships."

But as more influential countries join the AIIB, there is less reason to worry about purported Chinese domination of the new regional financial institution.

Though China will continue to be the host and leading donor country within the AIIB, its voting power will be progressively diluted by the participation of other major economies and regional powers.

It will be extremely difficult for China to unilaterally dictate the design and policies of the AIIB as advanced economies such as Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Singapore and, possibly, even Australia, Japan and South Korea, chip in - transforming the new financial institution into a more commercial and multilateral body, rather than a politically motivated mechanism for advancing China's interests.

So, the ultimate victory for China will be primarily symbolic. The failure of the US to dissuade major allies from joining the group heralds the decline of American soft power. In addition, it goes without saying that America's fiscal woes and highly polarised domestic politics continue to undermine its image as a reliable superpower which is willing and capable of checking China's seemingly revisionist - if not outrightly aggressive - designs in the region.

Dissuading allies from joining the Chinese economic bandwagon is increasingly a futile strategy. But Washington can enhance its regional diplomatic capital by decisively tackling its domestic challenges and augmenting its strategic footprint in the region, particularly in terms of trade and investment.

That is why the conclusion of US-led pan-regional trade agreements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership free-trade agreement, is critical to re-asserting US leadership in the Asia-Pacific region.

Still, many Asian countries continue to see the US as a source of stability and leadership in the region. Among treaty allies such as Japan, Australia and the Philippines, as well as strategic partners such as India, Indonesia, Vietnam and Singapore, the US continues to be seen as a crucial counterbalance to China's rising territorial assertiveness across the Western Pacific.

The battle for regional leadership is far from over, but the US will have to adopt a decisive counter-strategy in the coming years if it wishes to remain relevant in the region for the coming decades, especially as China emerges as a global economic pivot.

The writer is a political science professor at De La Salle University in the Philippines.