Healthcare costs rise at a much faster rate than general inflation: 30.6 per cent against 21.7 per cent between 2005 and 2015.

Government healthcare expenditure has also risen sharply. Its operating expenditure went up from $5 billion to $7.5 billion, or an increase of 50 per cent, between 2013 and 2015, according to the latest figures available.

What these figures show is what most people already know - healthcare is expensive, and getting more so. What many people also worry about: Will there come a day when the good healthcare system we take for granted is no longer affordable?

There are many drivers to rising healthcare costs, such as newer and better drugs and procedures, salaries, rentals and higher patient expectations.

But the biggest driver of all is the rising cost of private hospital and specialist care. Curb this, and we can curb rising costs.

Healthcare inflation can be broken down into inflation in the private and public sectors. Inflation in the private healthcare sector rose by 8.7 per cent a year between 2012 and 2014. In public healthcare, the rise was just 0.6 per cent a year.

What drives up costs in the private sector? In the Singapore system, there are two drivers that concern policymakers.

The first is rising fees charged by private-sector doctors.

The second is insurance, especially the role of "riders".

PRIVATE DOCTORS' FEES

First, private doctors' fees.

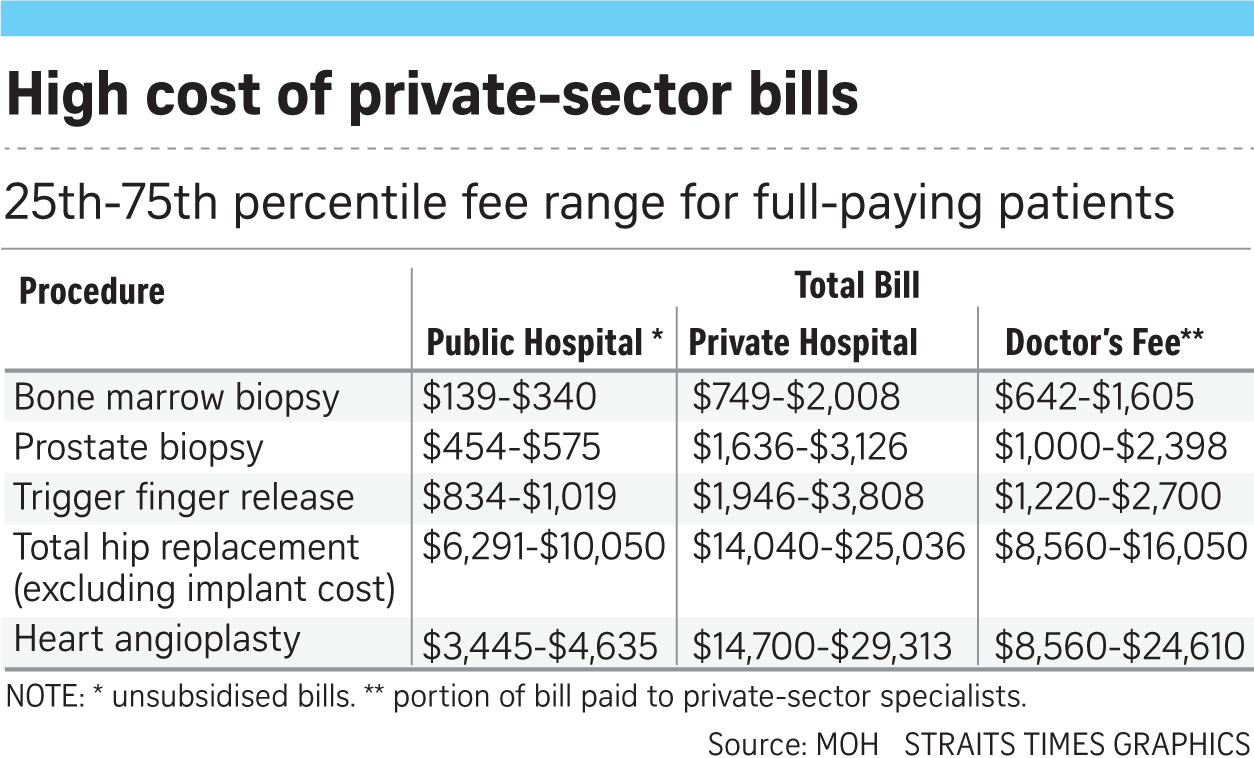

A report by the Health Insurance Task Force (HITF) six months ago had found that private hospitals' bills were about twice that of public hospitals for inpatient treatments. It was 21/2 to three times more for outpatient treatments, and four times more for day surgery.

The task force included representatives from the Ministry of Health (MOH), the Monetary Authority of Singapore and the Singapore Medical Association. It found that private-sector specialists' fees account for half of private hospital inpatient bills. In contrast, doctors' fees for private A-class (non-subsidised) patients at public hospitals make up less than a third of the total bill.

The higher charges by private-sector doctors raise the question of whether they are justified in charging the high fees.

It is undoubtedly true that some doctors are better than others. As in all professions, some are more skilled or more experienced, and deservedly charge higher fees.

The problem comes from the huge difference in charges between one doctor and another for the same procedure. Even for simple procedures, some doctors can charge three to four times more than others.

Take bone marrow biopsy. The procedure, where a thick needle is inserted into the bone to remove some of the marrow, costs full-paying patients $139-$340 (25-75 percentile range) at a public hospital. The bill can exceed $2,000 in the private sector.

Just taking the doctor's charges alone, at the 25th and 75th percentile of fees, private-sector doctors charge $642-$1,605. This means that one in four doctors charges more than $1,605 for the 30-minute job.

Why should that be a problem?

The short answer is that, unlike paying for a high-priced handbag or meal at a restaurant, higher medical bills are often paid by insurance, not by the person who uses the service directly.

Much of healthcare in the private sector is paid for by insurance. Insurance payouts come from premiums paid by everyone on the scheme. When medical bills go up, insurers have to pay out more. This pushes up premiums for everyone, not just the patients alone.

In other words, society as a whole ends up worse off when healthcare costs are not controlled.

THE INSURANCE FACTOR

In Singapore, there is some risk of health insurance costs spiralling out of control.

Singapore has MediShield Life, a national health insurance plan that covers everybody. In addition, two in three people buy additional insurance, called Integrated Shield Plans (IPs), that provides top-up payment to MediShield Life.

These IPs cover the bulk of private care bills. Policyholders need to pay only the deductible - the initial amount before insurance kicks in - and the co-insurance of 10 per cent of the rest of the bill. In addition, half the people who have IPs have also bought "riders" that pay for their portion of bills incurred.

How these deductibles, co-payment and riders work: Say your bill is $10,000. If insured under an as-charged private hospital IP plan, you would pay a $3,500 deductible and a co-insurance of $650. If you are covered by a rider; you don't even need to pay this $4,150.

A third of the population having riders means that many people do not have to pay when they are hospitalised, no matter the size of their bills.

The MOH fears that riders would push up healthcare costs and does not allow Medisave money to be used to pay its premiums, unlike premiums for IPs. In spite of that, the number of people with riders has gone up from one in five residents in 2011 to one in three today.

The MOH's fears are not unfounded. A study by the Life Insurance Association of Singapore found that patients with IPs and riders had bills that were 20-25 per cent higher than those of patients who had only IPs.

The task force noted: "As these policyholders are insulated from the cost of their medical charges, they may lack the incentive to manage their health and medical costs, translating to higher insurance claims."

This implies that the higher bills are not justified and are the result of overcharging or overservicing. Since the patient does not have to bear the cost, he is not concerned about the size of the bill.

If this trend of more people buying riders continues, insurers can expect to be paying out larger claims for more people. This will affect not just the premiums for riders, but also the IP premiums of people who do not have riders.

This means that the one in three people here with IPs but no riders is subsidising the higher bills of those with riders. Not only is this unfair to these policyholders, but it would also push up overall costs much more quickly.

Already, insurers have raised their IP premiums this year, from single-digit to 37 per cent.

Healthcare is one area where the size of bills can sometimes depend on the ability to pay rather than on the treatment itself. When that happens, everyone but the healthcare provider loses. As the HITF said: "IP policyholders will eventually bear the brunt of higher medical claims and higher insurance premiums."

Today, all six IP insurers offer riders. Five now offer "partial" riders that do not pay the entire patient's portion of the bill. For example, patients might have to pay the 10 per cent co-payment up to a certain cap. These "partial" riders have cheaper premiums.

This is a step in the right direction. But they may not be enough to stem spiralling costs, since the comprehensive "pay nothing" riders are still options.

This is where the MOH can step in, to disallow such comprehensive riders, and make partial payment of healthcare bills mandatory.

After all, co-payment has long been embedded in our healthcare philosophy. Riders make nonsense of the principle of co-payment.

People who have to pay even just a small part of the bill will be more inclined to check their bills and negotiate acceptable rates with their healthcare providers.

Another good way to keep a lid on runaway healthcare cost is to have a pricing guide for the private sector - as is the practice in countries like the United States, Canada and Japan. This gives both patients and insurers a norm against which to pay doctors.

As this is just a guide, doctors are free to charge higher amounts if they can justify doing so.

Such a guide can be used by insurers to work out how much to reimburse patients, with patients topping up the difference if they want a more expensive doctor. This checks costs and is more prudent than an insurance plan that pays "as charged" whatever the doctor or hospital asks for.

Singapore used to have such price guidelines issued by the Singapore Medical Association, but they were deemed anti-competition and scrapped a decade ago. However, if guidelines are set at the request of a government body like the MOH, it would not contravene the Competition Act. Doctors and MOH can draw up such a fee guideline.

Indeed, the HITF had recommended setting such fee benchmarks "to mitigate cases of over-charging by providers" and to give patients and insurers a reference.

A reasonable guide on fees would make exorbitant chargers stand out like sore thumbs - and hopefully lead them to reduce their fees.

In the complex landscape of rising healthcare costs, many cost drivers, such as rapid advancements in technology, may be beyond policymakers' control.

They can however concentrate their firepower on these two measures that can yield maximum benefit: Ban the offer of "pay nothing" riders by insurers, and publish a guideline on private doctors' charges.