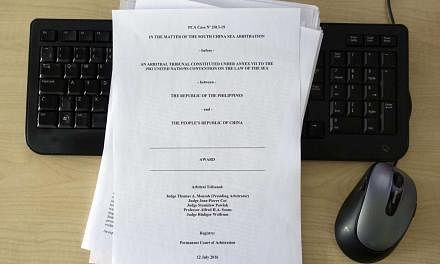

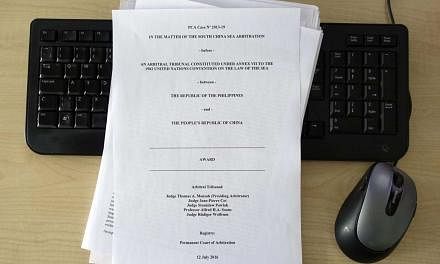

Following Tuesday's historic ruling on the South China Sea by the UN-backed Arbitral Tribunal at The Hague, two questions should be uppermost in our minds.

First, how will the ruling be assessed? And second, how might we expect the parties, and other claimants and stakeholders, to respond?

Where you stand on the ruling depends, of course, on where you sit. For the Philippines, which unilaterally initiated legal proceedings at the United Nations against China's sweeping maritime claims in the South China Sea in January 2013, the ruling represents a stunning legal victory.

Contrary to expectations, the five judges unanimously ruled in favour of almost all of the 15 disputes submitted by Manila, leaving observers flabbergasted by the sheer magnitude of the Philippines' victory.

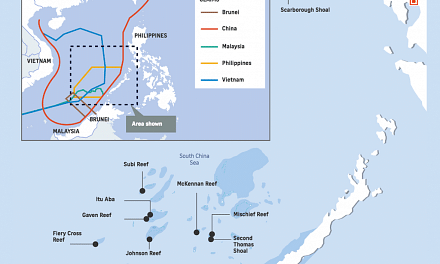

But for China, the ruling constitutes an overwhelming legal defeat and a reputational body blow. While it was generally assumed that the verdict would be unfavourable to China, it could not have been more unfavourable. The tribunal dismissed China's "historic rights" claim to oil, gas and fish within the so-called "nine-dash line" as incompatible with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), and ruled that even before Unclos came into effect, there was no evidence that China had "historically exercised exclusive control over the waters of the South China Sea". In short order, the judges blew China's nine-dash line out of the water.

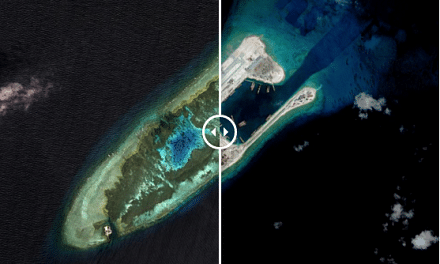

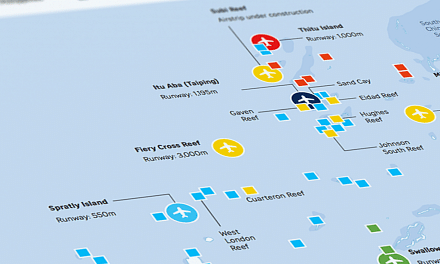

The tribunal also concluded that China had illegally violated the Philippines' sovereign rights in its 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) by harassing Philippine survey vessels and fishing trawlers, and undertaking massive reclamation projects during 2013-2015.

China's artificial-island building had, moreover, caused irreparable damage to the fragile coral ecosystem - thereby violating its obligations under Unclos to protect the marine environment - and aggravated the dispute between the two parties during the arbitral proceedings.

The ruling was also a punch in the stomach for Taiwan. It had argued that Itu Aba, which it has occupied since 1946 and which is the largest of the Spratlys features, is an island capable of sustaining human habitation and entitled to an EEZ.

But the tribunal ruled that none of the Spratly features are islands but mere rocks entitled to a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea or low-tide elevations with no maritime entitlements. The administration of President Tsai Ing-wen rejected the ruling, but made no mention of the nine-dash line. Beijing will likely see this omission as a dilution of "China's" claims, and cross-strait relations could suffer accordingly.

As for countries in South-east Asia that are either directly or indirectly involved in the dispute, the ruling can be assessed as their victory too, as the nine-dash line cuts into the EEZs of Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. In rejecting the nine-dash line, the judges upheld the sovereign rights of coastal states in their EEZs. It also vindicates Indonesia's position that no dispute exists between it and China in waters near the Natuna Islands.

How will regional governments respond to the award?

The ruling will be a cause for celebration for former Philippine president Benigno Aquino and his officials who lodged the submission in 2013. But it now falls to Mr Aquino's successor, President Rodrigo Duterte, to deal with the fallout. Mr Duterte was never enthusiastic about the case on the grounds that China was unlikely to abide by the outcome. Since taking office on July 1, Mr Duterte and Foreign Minister Perfecto Yasay have made conciliatory gestures towards China. Mr Duterte promised he would not "flaunt or taunt" a favourable ruling, and is apparently keen to hold bilateral talks with China to resolve their disputes. But even though Beijing has itself advocated such an approach, bilateral discussions might be interpreted by nationalist forces in China as an admission of defeat.

China's response has been predictable: Its foreign ministry immediately rejected the award as "null and void", and announced it would not comply with it.

What might China do next? Prior to the ruling, some experts suggested that the judges might include some face-saving provisions for China - in fact there were none.

As such, we can expect a visceral reaction from China. Beijing will characterise the verdict as a political conspiracy instigated by the United States, and will try to rally support from other countries to discredit the decision. Hardliners may call for decisive actions to underscore the country's territorial and jurisdictional claims, including declaring an air defence identification zone over the Spratlys, bolstering military forces on its artificial islands, and stepping up paramilitary protection for Chinese fishing vessels operating within the nine-dash line.

In the worst-case scenario, China might blockade Filipino Marines on Second Thomas Shoal, or start reclamation work at Scarborough Shoal. Such actions would greatly exacerbate tensions with the US in the South China Sea.

In the medium to long term, China may grudgingly acknowledge the ruling by bringing its claims into line with Unclos. But to do so would require a policy U-turn that will be difficult to sell to the Chinese people, especially given President Xi Jinping's strident assertions of sovereignty since taking office in 2012.

In the hours after the ruling, several South-east Asian countries issued anodyne statements noting the verdict. So far, none has explicitly supported the ruling beyond calling for respect for legal and diplomatic processes. In two weeks' time, Asean foreign ministers will gather in Vientiane where the award will dominate their discussions. Given the divisions within Asean - which China has deftly exploited in pursuit of its own interests, most recently in Kunming last month - calls by some members for a joint statement in support of the ruling could lead to renewed rancour and disunity.

As regional governments digest the full implications of the 500-page ruling, an interesting few weeks and months is in prospect.

Expect turbulent waters.

•The writer is Senior Fellow at the Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute. He is the co-editor of The South China Sea Disputes: Navigating Diplomatic And Strategic Tensions published by Iseas in May this year.