After five years, American-led negotiations over the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade liberalisation agreement with 11 other countries that collectively account for 40 per cent of the world's economy, are nearly complete.

The next step is for the United States Congress to allow for the same legislative process - an up-or-down vote on the deal - that it applied to recent trade pacts, including the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1993 and the US-South Korea free trade agreement of 2011.

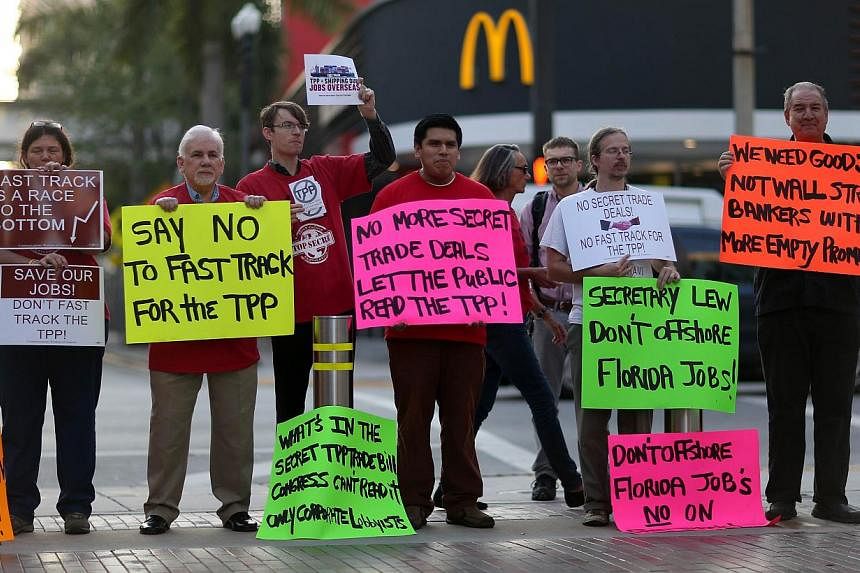

But the congressional outlook for this approach - called Trade Promotion Authority, or fast-track negotiating authority, because it does not allow amendments or filibustering - has dimmed. Without it, the agreement would collapse, the victim of endless amendments.

The coming vote, therefore, is the equivalent to a vote on the TPP itself. Should it die, the adverse impact on American national security would be great.

The trade debate coincides with growing challenges to America's allies.

In the Western Hemisphere, the governments of Canada and Chile, which are parties to the trade negotiations, believe the accord (despite domestic critics) will stimulate growth.

In Asia and the Pacific, parties to the deal - not only US allies Japan and Australia, but also Vietnam, Singapore and Malaysia - see the trade accord as a way of counterbalancing China's economic might.

This is why trade is central to our foreign policy; without this deal, the so-called pivot to Asia will be hollow.

Three myths are undermining support for the TPP in the US.

The first is that recent trade agreements have hurt jobs and wages, and widened income inequality. This argument fails to differentiate between the impacts of increased global trade and those of trade agreements.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist David Autor and colleagues concluded that from 1990 to 2007, Chinese imports accounted for 21 per cent of the decline in American manufacturing employment.

But the US does not have a bilateral trade deal with China. These jobs were lost to expanding trade - not to a trade agreement.

Yes, income inequality has widened to economically and socially harmful levels. But it is globalisation, technology and flawed educational and tax systems that are driving this, not trade pacts.

There is no doubt that increased trade has weakened the American manufacturing base, just as it has strengthened the service sector. This agreement, however, should not significantly increase imports of manufactured goods to the US. Six of the 11 other nations in the TPP already have free trade agreements with the US. And the other five face only minimal tariffs.

A second myth is that the TPP will degrade labour and environmental standards and raise drug costs. But the accord includes protections directly drawn from the International Labour Organisation, with strong enforcement mechanisms.

As for the environment, there is nothing new in the TPP that will affect existing dispute-resolution mechanisms. And it is far from certain that new protections for drug companies will lead to higher drug costs.

A third myth is that the TPP is flawed because it will not prevent countries from competing unfairly by devaluing their currencies to stimulate exports.

This criticism is short-sighted. When the Federal Reserve, having lowered its key interest rate to nearly zero, began extensive bond-buying in 2009, the trading value of the dollar fell against most other currencies.

There was severe criticism from Europe and Asia that the US was unfairly depreciating the dollar to improve its trade position.

Now, both the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan have initiated their own versions of extreme monetary easing.

And, in response, the trading value of the dollar has risen against the euro and the yen.

But the euro zone and Japan are not trying to start a trade war any more than the US was. The US should hope their policies succeed in spurring growth, because then their demand for American exports will rise. What is more, China, widely seen as the main culprit in currency manipulation, is not part of the TPP.

The International Monetary Fund should remain the venue for challenging what are judged to be illegitimate government interventions to drive down currencies.

The benefits of the TPP are many. It will further open the 12-nation region to trade in services and agriculture, two sectors in which the US historically runs large trade surpluses.

Better protection of American intellectual property will help industries, from high-tech manufacturing to Hollywood, in which Asian piracy has been rampant.

Free trade leads to greater overall prosperity. The gains from free trade need to be widely shared, but defeating the TPP will not solve America's problems with inequality. Instead, it will further rattle its allies.

"Further" is the key word here, as there already are rising doubts about American reliability - the result of the debt-ceiling crises, government shutdowns, the failure to follow through on threats in Syria and, most recently, the letter addressed to Iran from 47 senators.

If the TPP fails, countries that, rightly or wrongly, see Washington as ineffective will pay America less heed.

It is reasonable to debate the merits of this major trade agreement. But the critics have exaggerated and distorted the economic costs of the accord, while all but ignoring its benefits - and the strategic costs of a rejection.

The real choice is between supporting a trade accord that will help most Americans and serve the country's strategic aims, and defeating it, which will leave the country poorer and the world less stable.

Roger C. Altman, a former deputy Treasury secretary, is an investment banker. Richard N. Haass, a former director of policy planning at the State Department, is president of the Council on Foreign Relations.

NEW YORK TIMES