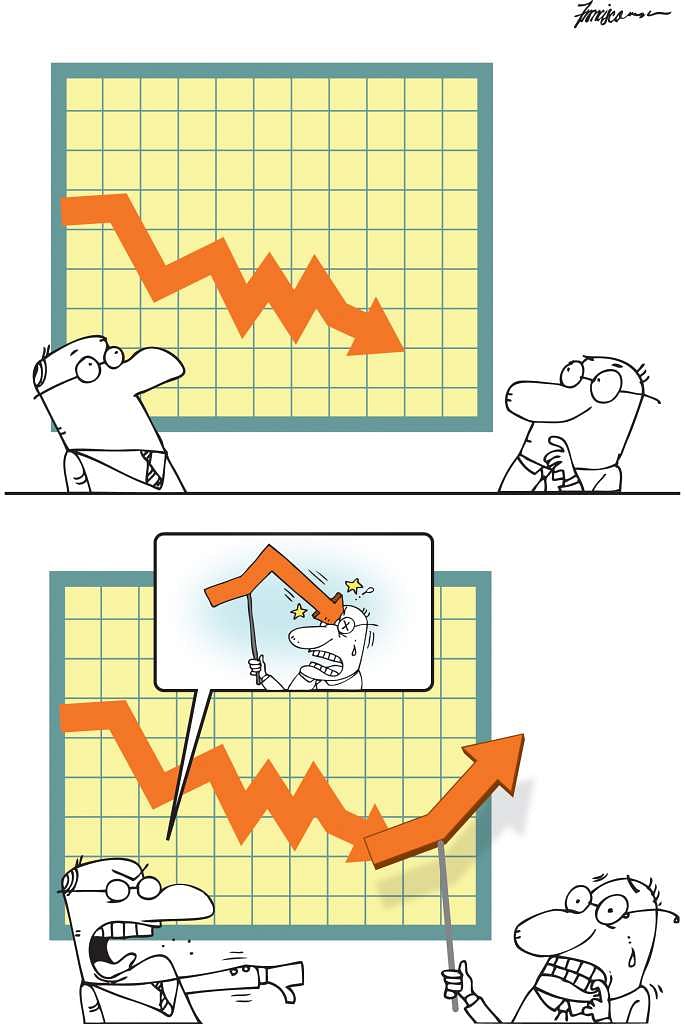

It is the emotional crowd that moves markets. Far-sighted government planners typically stay above the fray when it comes to short-lived rallies and outbreaks of panic on their stock exchanges.

So when organs of state start throwing their very considerable weight around to directly prop up falling share prices, they most certainly get noticed.

After a mid-June crash on the Shanghai bourse, Beijing officials made large-scale share purchases through state-backed funds, after repeated interest-rate cuts and other more creative efforts such as clamping down on short-sellers failed to reverse the bear market.

Earlier this month, Malaysia also said that it would directly intervene to help its ailing bourse by pumping RM20 billion (S$6.5 billion) into revived state investment fund ValueCap. The benchmark KLCI jumped the most in two years on the announcement, though the reassurance was likely verbal rather than fiscal, as government-linked funds have regularly given support to Bursa Malaysia.

But perhaps the most large-scale case of intervention in the world dates back to the Asian financial crisis in 1998, when the Hong Kong Monetary Authority spent an estimated HK$100 billion buying up blue-chip shares to stamp out hedge funds that had taken short positions against the Hang Seng index.

It worked at the time, though overall evidence is thin that such policies are effective. It's easy to attribute a trend reversal to other driving forces such as the local stock market mirroring the upward trend in other markets, or the simple eventuality of bargain-hunters scooping up undervalued shares.

In fact, the Hong Kong example is sometimes seen as an exception that proves the rule since it was one of the more well-directed initiatives - a safe bet on blue chips amid an irrational sell-off.

Beijing on the other hand made a less convincing debut, its panicked policies in support of a market-driven and state-guided bourse confusing rather than calming investors.

For now, the authorities seem to have stoked more market anxiety, to the extent that fund managers such as BlackRock have rewritten the disclaimers on the funds they manage to reduce their legal liability in the event of future state intervention, since an opaque Beijing machinery can surprise markets by pushing prices down the same way they surprised by pushing prices up.

The trillion-yuan lesson: "You can never fight the market no matter how big a war chest you may be able to accumulate," said CIMB Private Bank economist Song Seng Wun. "If the trend is against you, the best you can do is moderate volatility."

For these reasons, stock market crusades are hardly a policy maker's choicest tool, unleashed only in the most tumultuous of times to restore confidence to the market.

That these policies have made a comeback today suggests one thing - volatility has spiked to crisis levels and that makes the Chinese and Malaysian authorities very nervous. Nervous because excessive financial volatility creates uncertainty.

"If prolonged, that hurts business confidence, makes consumer and producer decisions more difficult - so activity slows down," said Barclays economist Leong Wai Ho. For example, people postpone large discretionary purchases when financial conditions are more volatile.

SLOW GROWTH, HIGH DEBT

Slow growth can dovetail with an environment of high debt to seriously crimp the real economy.

Asia - including Singapore - has borrowed cheaply and heavily in the post-financial crisis era of monetary stimulus.

But whereas Singaporean households tend to have strong household balance sheets, in countries such as Malaysia, household debt is close to 90 per cent of national income.

"In that sense, the stability of asset prices is crucial as any sharp downward movement is likely to trigger a vicious circle of margin calls and forced selling, which in turn leads to lower asset prices and yet more margin calls and forced selling," said Mr Kelvin Tay, chief investment officer for South Asia Pacific at UBS Wealth Management.

Leverage becomes a crucial pressure point in a recession, and can even drag out the recession when households must grapple with layoffs and debt servicing becomes a problem.

But with data showing slower credit growth and deleveraging risks in Asia, the decision by some governments to underwrite asset prices can seem counterproductive, as they stoke a false sense of security.

Still, most economists said it is not likely that the recent stock market interventions sought to prop up asset prices as a policy target.

"Rather, it's stability that they are looking for," said Mr Tay.

"I think most governments and central banks would be comfortable with asset prices that deflate gradually. It's the boom-and-bust cycle that they are trying to avoid or mitigate if it has already set in."

RISK AVERSION

Besides, the key risk in markets now is that investors tend to be "risk-averse" to a fault, rather than exuberant, said Mizuho economist Vishnu Varathan.

Asia is now more leveraged than it was at the end of the 2008 crisis, but nowhere as leveraged as it was in the run-up to the Asian financial crisis, a period marked by euphoria and hearty risk-taking.

This time round, markets have also endured a "rolling series of crises", said Mr Varathan. "From the euro zone crisis to the US debt ceiling crisis, to the 2013 taper tantrum - along the way there have been sell-offs, there have been corrections. These mini crises have helped to mitigate the risk of the so-called big one."

In fact, this risk aversion has been significant enough for some experts to suggest that the start of the US Federal Reserve interest rate hike cycle might even fuel demand by prodding those holding out on their investments to act now, since borrowing costs will only go higher.

For more evidence on how much volatility has spiked, just look at the lack of consensus on whether or not the world has, or has not, recovered from the last global recession. Even among the optimists, the US-led recovery is described as "nascent and fragile", prone to being derailed by uncertainty in China.

Which makes central banks' role as shock absorbers and guardians of market confidence all the more important in sustaining growth in a post-crisis world. Apart from taming equity markets, central banks today are also lenders of last resort for interbank liquidity, macro- prudential watchdogs for property markets, and the list goes on.

Sound policy, said DBS economist Irvin Seah, requires a combination of monetary and reform policies. "While monetary policy provides the buffer, domestic reform is the one that gets to the roots of the problem."