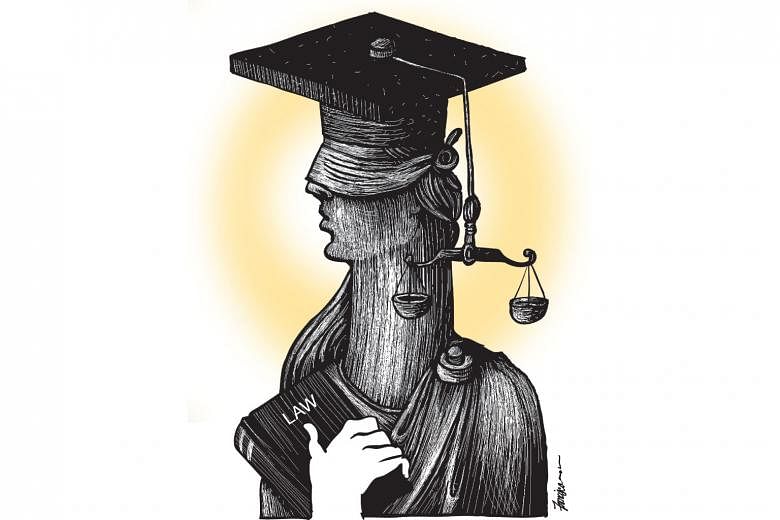

The 60th anniversary of legal education in Singapore offers a chance to look back on the history of the rule of law in Singapore - and forward to how the practice of law is changing.

Six decades ago, the first law students enrolled as colonial subjects in the new Department of Law of the University of Malaya. Four years later, the class of 1961 graduated from a faculty of what would shortly be renamed the University of Singapore, the country itself on the cusp of independence.

Given the importance of the rule of law to Singapore today, it may be surprising to learn that the study of law had earlier been actively discouraged by colonial authorities, here and across much of the British Empire. This was sometimes justified as a question of priorities - engineers, doctors and agriculturalists were said to be more useful in a developing economy. But it is also clear that lawyers were viewed with suspicion as potential troublemakers.

Speaking in 1959, Singapore's founding Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, who had studied law at Cambridge, opined that the British learnt from the mistake of allowing legal education in India: "They knew that large numbers of lawyers meant large numbers of self-employed intellectuals who were well-versed in the mechanics of the colonial system and who then set out to lead the mass of the local people in breaking down the colonial system."

People like him, in other words.

Such wariness of the dangers of a legal training continued into independence, with various efforts to match the number of law graduates to the number of lawyers required by the economy. Indeed, those efforts continue today in tweaking the domestic and international supply of lawyers.

A decade ago, what is now the National University of Singapore Faculty of Law lost our monopoly status, welcoming some healthy competition from the Singapore Management University and, more recently, the Singapore University of Social Sciences - both law schools headed, I am proud to note, by members of our alumni (classes of 2006 and 1978 respectively).

Indeed, from a dearth, it has been suggested that we now have a "glut", as Minister for Law K. Shanmugam (class of 1984) put it, though this is primarily due to the fact that there are now more Singaporeans studying law in England than in all three local universities combined. Unfortunately, a large proportion of those graduates who spend thousands of pounds on their degrees later fail the bar exam necessary to practise law in Singapore.

The importance of educating lawyers in Singapore is no longer questioned. Indeed, it is recognised as vital to our aspirations to be a dispute resolution hub and underpinning other sectors of the economy, most obviously financial services. Legal academics today are not only expected to produce highly-qualified graduates, but also to help position Singapore as a thought leader in legal research.

Yet if the supply side of legal education in Singapore has changed, this is nothing compared with the transformation in demand.

Speaking at NUS Law's 60th anniversary dinner in October, Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon (class of 1986) challenged us to prepare students for a globalised profession, to instil a commitment to public service, to embrace the opportunities of the digital revolution and to examine whether our current admissions process is best suited to identifying those who will thrive in the profession.

In the first two of these areas, we are making progress. On globalisation, fully half of our students spend a semester or more on exchange, some earning a master's degree in their fourth year through partnerships with New York University, King's College London and other leading schools.

The rest benefit from the diverse students from around the world who join our upper years. We are nonetheless exploring more ways for students to travel for shorter periods, in particular, exposing them to jurisdictions in Asia. The hope is to enable them to take advantage of the growing market for legal services exported from Singapore. As Senior Minister of State Indranee Rajah (class of 1986) reported earlier this year, the value of that market more than doubled between 2008 and last year.

On public service, we launched a new Centre for Pro Bono and Clinical Legal Education in October this year, with the aim of broadening and deepening the opportunities for students to see the law in action with real clients, real problems and real consequences. This echoed a sentiment expressed last month by President Halimah Yacob (class of 1978) in her first speech as NUS chancellor, in which she stressed the importance of the university developing its strong tradition of service.

Law and technology is a faster moving target, but with tremendous opportunities in both education and research. We now offer courses on everything, from data protection to the law of artificial intelligence, but are considering more radical ideas, from specialist degrees to including coding as part of the first year at law school.

On the research front, questions raised by the digital revolution range from governance of smart contracts and blockchain to liability for damage caused by autonomous vehicles. In some cases, our students are racing ahead of their professors, with student groups such as Alt+Law and legal analytics start-up Lex Quanta.

Admissions is another area that we continue to study. One modest step is an increase in our discretionary shortlisting from 10 to 15 per cent, meaning that candidates are selected for an interview and written test not solely on academic marks. At the same time, we are committed to ensuring that no deserving student is unable to take full advantage of a place in law school for financial reasons.

More radical possibilities exist here too, such as making law a graduate degree, as it is in the United States, a model embraced by my own alma mater, Melbourne Law School, a decade ago.

Legal education, then, has long been tied to the expansion of the legal sector in Singapore, while the rule of law remains vital to the fate of the country as a whole.

The cohort of students that commenced studies 60 years ago was a remarkable group of men and women. Professor Tommy Koh later served as Singapore's first ambassador to the United Nations, Mr Chan Sek Keong as attorney-general and later chief justice, Dr Thio Su Mien as dean of the Faculty of Law, Mr Koh Eng Tian as solicitor-general, Mr Goh Yong Hong as police commissioner, Mr T.P.B. Menon as president of the Law Society, and so on.

They were the first of 10,000 graduates who now occupy leading positions in the profession, such as Attorney-General Lucien Wong (class of 1978), public office, such as former deputy prime minister S. Jayakumar (class of 1963), as well as in diverse fields such as the arts (Mr Ivan Heng, class of 1988), fashion (Ms Priscilla Shunmugam, class of 2006), and technology (Mr Tan Min-Liang, class of 2002).

On behalf of them, and indeed on behalf of all lawyers, let me take this opportunity, in my last piece in these pages for the year, to wish you (but in no way to guarantee or assume liability for) a reasonably merry Christmas and/or festive period.

Terms and conditions apply.

- The writer is dean and professor of the National University of Singapore Faculty of Law.