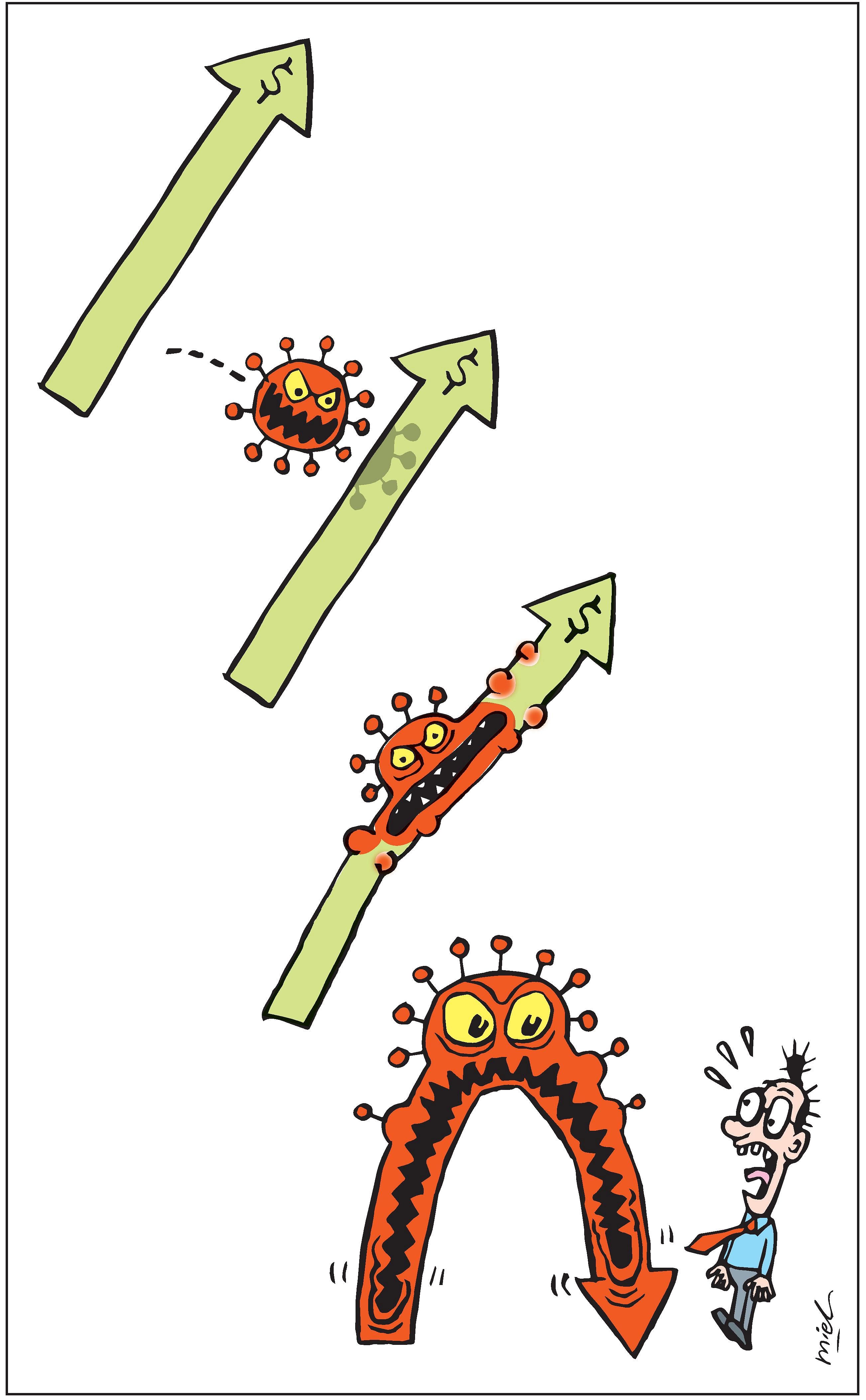

Economic crises have a tendency to morph. After a crisis gets under way, its epicentre can shift and it can turn contagious in unpredictable ways, impacting areas previously presumed relatively safe.

For example, what starts as a domestic crisis can take on regional dimensions, affecting even healthy economies, as we saw in Asia in 1997, or go global, as happened after the United States subprime mortgage crisis of 2007-2008. Crises can also spread quickly from one sector to another and then engulf entire economies. Europe's real estate crises in 2008 morphed into banking crises a year later and then into a euro zone-wide sovereign debt crisis by 2012.

Covid-19 started out as a health crisis, which it still is. But it quickly became an economic crisis in the face of lockdowns, supply chain disruptions and the near-total closure of industries such as international travel and tourism, parts of retail and hospitality, live entertainment and nightlife.

With vaccines being rolled out, economic recovery is now within sight. Yet, there is reason to believe that we may still be only at the end of the beginning of what could become yet another rolling crisis.

In an interview with The Straits Times, Mr Alfonso Garcia Mora, vice-president for the Asia-Pacific at the International Finance Corporation (IFC) - the World Bank's private-sector lending arm - provided some clues as to what might lie ahead, and what needs to be done.

The immediate impact of Covid-19 on companies, he pointed out, was a shortage of liquidity because of the collapse of demand and the disruption of supply chains, which led to severe cash flow problems. This was largely resolved, mostly by central banks, which pumped huge amounts of liquidity into economies.

The coming solvency crisis

But central banks can't deal with solvency issues, which are the next threat. The demand shock has led to solvency problems because many companies can't pay their essential expenses. "This is what is unfolding now," said Mr Garcia Mora, especially in the sectors worst impacted by the crisis, such as tourism, which in some countries accounts for as much as 10 per cent of gross domestic product.

Across economies, about half of firms won't be able to service their loans. Bankruptcies could increase by 30 per cent in the Asia-Pacific over the coming year, he said.

So far, bankruptcies resulting from the Covid-19 downturn have remained largely bottled up, mainly because of government assistance, relaxed bankruptcy laws and forbearance by banks. In Singapore, for example, besides providing financial support, the Government has mandated moratoriums on legal action over rents and contracts, and raised the thresholds for bankruptcy and insolvency proceedings. Banks have been allowing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to defer repayments since April. They might extend the deferrals beyond this year on a case-by-case basis. Many other countries have adopted similar measures.

But when the economic recovery gets under way, the forbearance by banks will end and laws will revert to normal. The lagged effects of negative growth will also start to be felt. That is when bankruptcies could start to take off.

A shock for banks

Rising bankruptcies could deliver a rude shock to many banks, which may not have been monitoring the solvency of their borrowers during the forbearance period. So while, right now, banks' non-performing loans (NPLs) may seem low and manageable, the picture could change dramatically once forbearance ends, and the later it ends, the more dramatic will be the change.

"When forbearance was announced, we thought it would last three months to six months," said Mr Garcia Mora. "But we have already passed nine months, and there may be three to four months more to go before forbearance ends." When that happens, banks could discover that their NPLs are not 2 per cent to 3 per cent as they were six months earlier, but in double digits.

"The banking sectors of some countries could become stressed, especially those that entered the crisis with already weak financial sectors," said Mr Garcia Mora. "As of today we don't have enough information to say whether banks will need to be bailed out, but we expect there will be cases which will need support."

Covid-19 has already morphed from a health crisis into a crisis of negative growth and rising unemployment. It could morph further into a corporate debt and banking crisis. So what needs to be done?

Dealing with insolvencies

The first order of business should be for countries to create strong frameworks to deal with insolvencies. Many countries in the Asia-Pacific don't have one, Mr Garcia Mora pointed out.

The goal should be to ensure, first, that firms which are still solvent, but facing cash flow problems, restructure so they can continue operations; and second, that firms which have become unviable go into bankruptcy and get liquidated.

Mr Garcia Mora proposed that ideally, these issues should be tackled through out-of-court processes. "There shouldn't be a need to go through the judicial system, which can be slow and cumbersome," he said. "Formal bankruptcy proceedings might be appropriate for large corporates with complex structures. But the structure of most SMEs is relatively simple. So what is needed are fast processes that can be implemented immediately."

He is hesitant to recommend that governments take equity stakes in troubled companies. One problem is that having already run up huge fiscal deficits during the Covid-19 crisis so far, most governments lack the fiscal space to bail out companies on a large scale. Another is that mechanisms for the government to unwind its investments can be problematic. "There are many cases where governments have bailed out private firms and there was no way for those governments to exit for a long time," Mr Garcia Mora said.

A preferable solution, he suggested, would be for governments to "crowd-in" the private sector to take over viable but troubled companies, by providing seed financing or guarantees. Only in cases where private capital is not forthcoming, there are clear pathways to exit, and bailouts are in the public interest, should governments take equity stakes.

Reallocating capital

Once insolvencies are dealt with, the next priority should be to accelerate the economic recovery by channelling liquidity selectively to deserving sectors. What will be needed, Mr Garcia Mora said, is "a massive reallocation of capital".

This will be a tricky exercise. The general manager of the Bank for International Settlements, Mr Agustin Carstens, has pointed out that while economic growth will eventually return, "the engines will not be the same... the economic landscape may have fundamentally changed".

There will be more digital adoption in several sectors, and consumer attitudes will have changed and may never return to what they were, pre-pandemic. There will, for example, be more remote work, less travel, less offline shopping and less eating out. While such trends will strengthen some sectors, "they will also turn once-thriving sectors into deadwood". If policymakers try to prop up businesses in these sectors, they could add pressure to the banking system and exacerbate the economic contraction as well as job losses.

Deciding which sectors merit support won't be easy, Mr Carstens added. "Pre-crisis performance alone will not provide an accurate guide." Banks can help identify the appropriate targets. But they too would need to revise the types of clients they lend to. Thus, as the Covid-19 crisis morphs, the responses to it - from governments, banks and companies - will also need to change.

IFC's response to Covid-19 and Singapore's role

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) is responding to the Covid-19 crisis with what Mr Alfonso Garcia Mora, its vice-president for the Asia-Pacific, calls "the three Rs" - relief, restructuring and recovery.

By way of relief, it has provided US$8 billion (S$10.7 billion) for working capital liquidity to firms in countries whose central banks were not able to come up with enough liquidity support. It also extended US$4 billion in financing for health, including support for countries to develop and distribute vaccines, pharmaceuticals and personal protective equipment.

It is also helping many of its client companies to restructure their businesses for a changed world and is working with banks to resolve non-performing loans and take them off their books, to unlock fresh lending.

The IFC wants to promote "a resilient recovery". This will involve several elements, according to Mr Garcia Mora.

A crucial step will be to expand digital connectivity. "There are about 3.5 billion people in the world who are still offline," he pointed out, which means they cannot benefit from rising digitalisation.

In many poor countries, only one out of 25 jobs can be done from home. "This pandemic is a crisis of inequality, which has increased significantly across countries, social classes and genders. Women have suffered 1.8 times as many job losses as men," said Mr Garcia Mora.

The World Bank group has launched a Digital Development Partnership to work with the private sector to promote digital transformation in the developing world. Google and Microsoft are among the companies that have signed up as partners.

A resilient recovery will also involve helping firms to access green finance and blue bonds (which raise funds for ocean-friendly projects), and build green infrastructure. These are areas where the IFC will be redoubling its efforts.

Last Wednesday, its parent, the World Bank group, raised its commitment to climate-related lending to 35 per cent of lending operations, from 28 per cent.

Singapore is critical to the IFC's Asian operations. It has the largest presence among all international financial institutions here, with more than 150 staff, who work on countries ranging from Afghanistan to the Pacific Islands.

"For us, Singapore is a vital knowledge hub for digitalisation, fintech and climate-related issues," said Mr Garcia Mora. "It is also a hub for infrastructure financing. We are mobilising private capital from Singapore. We want to help Singapore companies go overseas, where we can identify good opportunities and co-invest with them."

The Covid-19 crisis has opened up many new opportunities for companies in Asia, he added.