From a peninsula that is too often a source of strange, horrifying stories, this is one of the weirdest. Some details are still hazy: history is usually that way in the Koreas. But there are enough for a compelling tale. It's the story of two Korean dictators - the North's Great Leader Kim Il Sung and the South's President Park Chung Hee (both now dead but by no means forgotten) - and their plans to assassinate one another.

The Great Leader of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) once denied that he had anything to do with the imbroglio, but you may safely bet Pyongyang to a penny that the "Ever-Victorious, Iron-Willed, Brilliant Commander" (as his friends liked to call him) was, at the very least, indulging in Trumpian truthiness.

Events began unrolling in January 1968, when a band of 31 highly trained fighters, sworn to suicide if necessary, set out from their camp high in the North Korean mountains and began a 60km march to the centre of downtown Seoul and the Blue House, as South Koreans of the Republic of Korea (ROK) call their presidential palace. The men, all in their 20s, were from an assault team of the North Korean army's 124th Unit.

The unit's recruits were ordered to use South Korean accents and slang. Training was exceptionally rigorous. They were expected to be marathon runners, sprinting for miles over icy terrain while carrying about 30kg of gear. They had to climb a 1,000m mountain in a snowstorm. To toughen them for the ghastliness of combat, they were forced to sleep on corpses.

For their final, week-long pre-mission exercise, a provincial headquarters building had served as the "Blue House". Combat realism was not lacking: some 500 militiamen pretended to be ROK defenders in hand-to-hand fighting that became progressively more violent. About 30 of them were hospitalised.

Just ahead of the commandos' departure, the North Korean Public Security Ministry's chief intelligence officer, Lieutenant-General Kim Chung Tae, gathered them for a final meeting and issued a brief, blunt order: "Go to Seoul and cut off Park Chung Hee's head!"

They were also to kill any staff they found in the Blue House, and, indeed, anyone who got in the way of their mission. Mr Park's assassination by what appeared to be Southern soldiers, he told them, would spark an uprising that would leave South Korea vulnerable to an imminent invasion by the North.

MAKING GOOD SOLDIERS

For many decades, the dominant political-military philosophy in this part of the world had been Japan's Bushido (literally, the way of the warrior), a code stressing unquestioning loyalty and obedience and valuing honour above life. World War II and the Japanese colonisation of Korea were very much fresh memories, such as Japan's "Three Alls" policy (sanko sakusen - "kill all, burn all, loot all").

Koreans also have a quasi-martial philosophy, Hwarang ("Five commandments"). Noteworthy are Commandment 1: "Be loyal to one's lord"; and Commandment 4: "Never retreat in battle".

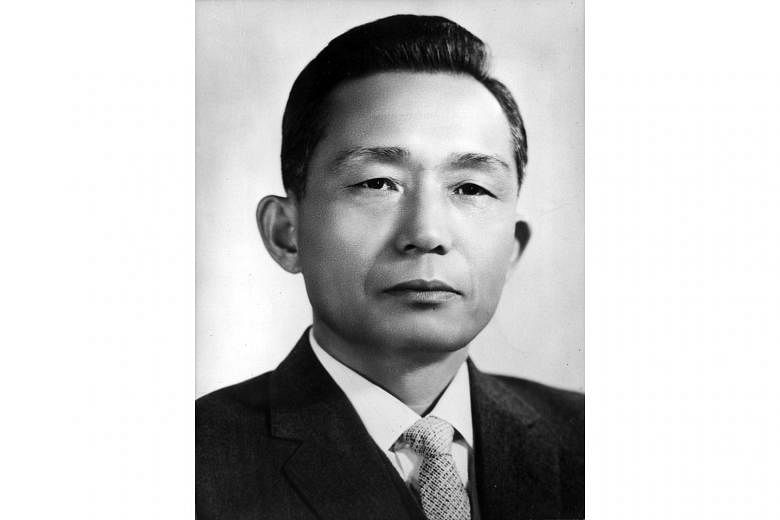

The men who would ultimately emerge as the Koreas' two leaders found that men formed by such teachings made very good soldiers indeed. In their youth, the North's Mr Kim and the South's Mr Park had had experiences steeped in these martial lifestyles. Mr Kim had led a small guerilla band fighting a much larger Japanese army. Mr Park had actually taken a series of Japanese names in order to serve in the Manchukuo Imperial Army. This puppet force, effectively a branch of the Japanese army, spent much of its time hunting (and dealing unpleasantly with) Koreans like Mr Kim who resisted Japan's colonialist rule.

The United States' use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki abruptly put an end to this warfare in 1945. The US and the Soviet Union agreed to divide the Korean peninsula's post-war occupation along the 38th Parallel. Over the next few years, two fiercely competitive governments emerged in the North and South: Mr Kim's DPRK allied with fellow communists in the neighbouring Soviet Union and China; and Mr Park's ROK linked its fortunes to the Americans, who maintained substantial military forces in nearby Japan.

The devastating Korean War (1950-53) ended in stalemate along the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ), a strip of land separating the warring armies. Although there was only an armistice and the war has never stopped for good, military clashes became limited to low-intensity conflict, especially clandestine activity by both sides' commandos.

Mr Kim and Mr Park took brutal care of their respective leadership arrangements. By the late 1960s, Mr Kim's purges of potential rivals put him well and truly in command of the ruling Korean Workers' Party and the DPRK. In the wake of a coup in Seoul in 1961, Mr Park had seized control of the ROK government.

THE LONG TREK SOUTH

Koreans have a wry saying about their country: "Beyond the mountains, more mountains." The region from which the North's Unit 124 commandos left - Kaesong - was enduring a particularly bleak winter in 1968 and the 60km trek south was no stroll in the garden.

First, they had to slip through a sector controlled by the US 2nd Infantry Division. Only a few kilometres from divisional headquarters they had their first serious setback: four local (that is, South Korean) woodcutters stumbled upon their forest encampment. The teenagers, all brothers, were immediately taken hostage.

If the commandos had followed their orders strictly, they would have slaughtered them on the spot. One faction in the group favoured this. But the warrior code is sometimes tempered by mercy. The commandos' mercy faction spent five hours explaining the superiority of the Great Leader's communism and lecturing them on the inevitability of Korean reunification before the year was out.

Then, after extracting promises that their prisoners would not tell anyone what they had seen and threatening savage reprisals against them and their family members if they did, they let them go. One of the brothers was given a cheap Japanese watch to compensate for the loss of a day's work.

Perhaps a possible, even likely, explanation for the risk taken in freeing the brothers was the profound faith young Korean commandos had in their Great Leader's teachings and in their conviction that South Korean woodcutters would soon be part of the same community. In any event, the crash course in Kim Il Sungism failed to stick. As soon as they were out of the forest, the woodcutters took their bizarre news straight to the local police, who contacted the ROK army. An all-points alert was sounded; counter-guerilla operations were quickly under way.

Sticking to mountainous terrain, the intruders kept moving south. About 5km north of Seoul they established their next camp. On Jan 21, they removed overalls that had been covering ROK uniforms and buried all their supplies. Sporting ROK sub-machine guns and hand grenades, the 31 split into smaller groups, moved into the city, then reunited 1.5km from the Blue House for their final assault.

They almost made it. The reunited group brazenly marched in column formation towards the presidential palace. At about 10pm, a policeman challenged the column's lead soldier for identification. The Northerner responded, "We're with counterintelligence from the 26th Infantry Division", and kept his men marching on.

But the policeman remained suspicious. He would later say that the group's leader seemed "too complacent" about the guerilla alert. As the column passed, the policeman tried to detain the last man, demanding further identification.

A firefight broke out. Two ROK soldiers and three policemen were immediately wounded. To distract defenders, one intruder threw grenades at two civilian buses; two civilians were killed.

Throughout the rest of the night and most of the following day, deadly skirmishes continued up to within 800m of the Blue House. Four intruders were killed, then two captured, one of these killing himself with a concealed grenade.

Three days later, ROK soldiers captured one surviving Northerner, Kim Shin Jo. Exhausted and starving, he revealed the route by which his colleagues planned to escape north. In the ensuing mop-up, a further 23 infiltrators died. Two reportedly made it back to the DPRK. One of these - a certain Pak Jae Gyong - will be heard from later. The manhunt was costly for the South: 27 soldiers died and 65 were wounded in the operation.

Needless to say, the Park administration gleefully reported the North's failure: A military textbook, North Korean Special Forces by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr (Naval Institute Special Warfare Series, 1998), and a long article in Reader's Digest (Mission: To Murder A President, July 1968) covered the events in detail. But eventually the Blue House Raid dropped from view.

AVENGING THAT WENT WRONG

Until a few months ago.

News reports from Seoul indicate that Pyongyang's nuclear and rocket testing may have revived that old knife-fight plan. Last September, South Korea's Defence Minister Song Young Moo told lawmakers in Seoul that the government was forming what special forces officials were calling a "decapitation unit" with North Korea's Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un in mind. "The unit has not been assigned to literally decapitate North Korean leaders," The New York Times hastened to explain, "but that is clearly the message South Korea is trying to send".

Overnight, the Internet came alive with memories of another incident. It's known as Silmido, after an islet made famous by the events and a 2003 movie that told the long-secret story for the first time. This was the tale of President Park Chung Hee's April 1968 plan to send a similar special force (named Unit 684 for that date) to Pyongyang to avenge the Blue House attack eye-for-eye, throat-for-throat.

As former drill sergeant Kim Shin Jo, who had helped train the South Korean commandos, has put it: "Their goal was to blast into Kim Il Sung's palace in Pyongyang and chop off his head."

Silmido was also a failure, but a rather longer, more complicated one. The ROK army did not detail its best and brightest for the venture. Instead, as the training team's surviving members tell it, they recruited ex-cons and ruffians off the streets, telling them they would receive money and the chance of an honourable relaunch of their lives if they accepted the onerous mission.

Silmido is a bleak, nondescript stretch of land about 60km west of Seoul. History buffs visit it in search of traces of what happened here. Some of the ROK army's most feared instructors put Unit 684 through unimaginably brutal training. Seven of the young conscripts died.

In October 1968, after exercises that killed three from the unit, P (for Pyongyang)-Day was declared. The order came from Seoul to set out in rubber boats for North Korea. But with their sortie still in its earliest stages, word came from the Blue House cancelling the operation.

The precise reason for the halt is lost to history - many Unit 684 records have gone missing - but the best guess is a brief warming at that time of relations between Washington and Moscow. Mr Park's regime, it's thought, did not want a flare-up in Korea to be the reason for upsetting fragile US-Soviet detente. Unit 684 returned to Silmido, and its commanders recommended that it be disbanded.

But no response to this proposal came from Mr Park. The harsh training regimen was renewed, continuing unrelentingly for another three years. No further orders came from the Blue House. Unit 684 appears to have been forgotten.

When it seemed that there would be no release from increasingly pointless torment, Unit 684's mood gradually turned ugly. On Aug 23, 1971, in the wake of a night of heavy drinking, mutiny broke out. Some in the unit broke into their commanding officer's room and smashed in his head with a hammer. Another 17 of their 24 trainers were then murdered, most of them as they slept.

After stealing ammunition, about 20 mutineers commandeered a boat and then a bus and set out for Seoul. Their destination was the Blue House, says trainer Kim Yi Tae, one of the only six to survive the massacre of the instructors. "They wanted to find President Park and complain they'd been overlooked."

Armed soldiers stopped the bus on Seoul's outskirts. Twenty Unit 684 members were shot or committed suicide with grenades. A court martial organised by persons who clearly wanted to bury the story of the debacle sentenced four survivors to death and they were promptly executed.

Then, 32 years later, the Silmido movie publicised the affair. Families of abandoned commandos were encouraged to seek compensation. In 2010, courts ordered the government to pay nearly US$300 million (S$396 million) in damages.

AND WHAT OF PROTAGONISTS?

Our tale of the two Koreas' knife-fights is rich in irony.

When Seoul first put the Silmido survivors before a court martial, they described those sad, mutinous, but nonetheless intrepid agents of the Seoul administration as "armed communist agents".

And Kim Shin Jo, that Northern remnant of the Blue House Raid?

Kim settled in Seoul and married a local who introduced him to an alternative tract to Bushido and Hwarang - the Bible. He eventually became a Presbyterian pastor. When he took ROK citizenship in 1970, his parents back in the North were reportedly executed. An interview of him currently appears on YouTube (https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=e8hAUW6-n14).

A photograph of his capture 50 years ago may be found today on his Facebook page labelled "Kim Shin Jo (spy)".

And Pak Jae Gyong, the DPRK commando who made it back to Pyongyang in 1968?

Pastor Kim believes that he recognises his former marathon-running comrade in photographs as "a man with a pot belly" in a North Korean major-general's uniform. Over the years, Pak had reportedly become DPRK armed forces vice-minister. In September 2000, he visited Seoul as part of a delegation invited by the ROK and presented the South's then President Kim Dae Jung with a gift from Pyongyang of three tonnes of pine mushrooms, a Korean delicacy.

If Pastor Kim is right and that is indeed Pak, the North Korean did perhaps - finally - reach the Blue House.

•The writer is a former editor-at-large (Asia-Pacific) for Fortune magazine of New York and a member of London's International Institute for Strategic Studies.