When he was alive, Pan Shou was honoured as a great poet and artist and celebrated as a national treasure. But since his death in 1999, he seems to be gradually fading from Singaporeans' memory.

His works are not as widely read or studied in schools as they should be. His old residence has been sold and most people no longer remember where he used to live. When news of his ashes being buried in Perth, with a tombstone bearing no inscription of his name in Chinese characters, came to light in 2015, it caused hardly a ripple. People walk past his calligraphy, which can be found all over Singapore, oblivious of the fact that it is his work.

The question of how to remember pioneer artists like Pan, who have made significant contributions to Singapore, rarely emerges in public discussions. It was, therefore, especially encouraging to see two events last month that honoured the legacy of artists whose contributions were truly outstanding, through meaningful art projects that sought to stir reflection on the importance of their lives and work.

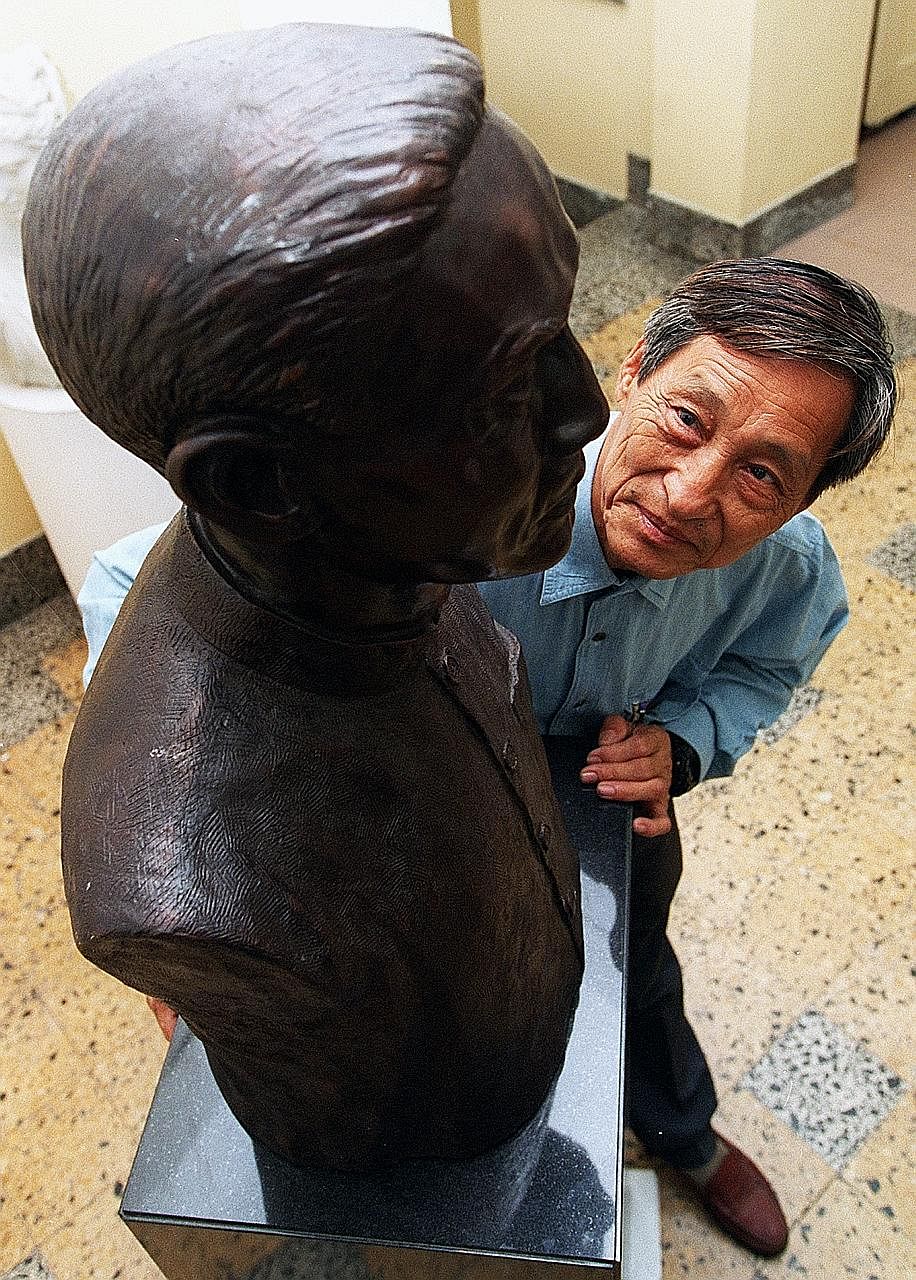

On Aug 12, gallerist and photographer Chua Soo Bin, with the help of artist Cheo Chai Hiang, launched a special sculpture dedicated to the memory of sculptor Ng Eng Teng.

The gallerist had intended to create a public art installation with timber salvaged from Ng's demolished residence in Joo Chiat, where the artist had lived and worked before he died in 2001. But his original plans fell through, resulting in a work on a much-reduced scale being installed in the garden of his residence in Upper East Coast Road.

While it is great for an enthusiastic and generous individual to create entirely at his own expense an artwork in his private garden to remember Singapore's leading sculptor, one cannot help but wish the commemoration could have been done on a grander scale in a public place so that more people could have participated in it.

Last month also marked the opening of artist Tang Da Wu's exhibition, "Hak Tai's Bow, Brother's Pool and Our Children", which took place at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (Nafa). It featured two large installations dedicated to the respective founders of Nafa and the LaSalle College of the Arts.

In these works, Tang paid homage to two founders whom he thinks Singapore is hugely indebted to for making possible the vibrancy of today's visual arts scene, through their pioneering work in art education. "I feel deeply grateful to them," the artist said emphatically.

Hak Tai's Bow consists mainly of six sets of larger-than-life steel skeletons of horses, representing the six guiding principles of Nafa's mission, and a huge bow, half of which is in the form of the Chinese character gong (bow) in steel. The work is on display at Nafa until Oct 8.

Brother's Pool consists of a circular enclosure, symbolising a pool filled with creative energy in the form of rocks from Brother Joseph McNally's studio.

Actively involved in education himself, Tang thinks Nafa founder Lim Hak Tai is much lesser known than Brother McNally despite his relative importance. He finds it shocking and even unthinkable that many people have never heard of Lim.

"His contributions were tremendous," Tang said, referring to Lim's last words to his son Yew Kuan in 1963. He had said: "The one thing I have done right in my life is to found the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts."

Lim saw Nafa through some of the most difficult years since its establishment in 1938 with only 14 students. To make ends meet, he even donated his own salary back to the academy.

Lim also inspired his Malaysian student Chung Cheng Sun to set up the Malaysian Institute of Art in Kuala Lumpur after graduation in the 1960s.

The same inspiration led Chung's daughter Chung Yu, a trained botanist, to publish a book on some aspects of Malaysian art tracing its origins back to Singapore.

Indeed, Lim's remarkable vision is at the core of Tang's installation, presented on a monumental scale of public art. The six horses in the form of steel skeletons, to stress the fact that this is what remains and endures when the body is long gone, are symbols from an earlier painting in ink of the same title depicting the Nafa founder as Shiva, a Hindu god, holding a bow with six galloping horses.

The horses forging ahead give form to Lim's six guiding principles laid down in 1955 as: integration of cultures and customs of the various races; bridging the art of the East and the West; development of the spirit of science and current social thinking of the 20th century; expression of the local flavour through art; reflections of popular demands of local people; and emphasis on the educational and social functions of fine art.

It was Lim who recruited Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Wen Hsi, Chen Chong Swee and Georgette Chen, who were regarded as among the best of the academy's teaching staff. It was also Lim who encouraged these artists to travel to Bali in 1952 in search of a new art form. That is why he is often described as "the father of Nanyang art", a style of painting that mixed techniques from Chinese tradition and the Paris school and sought to depict scenes from this region, known in Chinese as Nanyang or the Southern Seas.

Though all of Nafa's teachers, including Lim, had come from China, Tang chose Hindu iconography to project the heroic image of the school's founder by painting Shiva in a chariot wielding a bow. The bow is a symbol of protective power in Indian culture, as in many others, as a leader must, to show good judgment and balance, string it just right - neither too loose nor too tight.

Shiva, as a destroyer of evil forces, also embodies the purifying and creative energy of the universe, which is also symbolised by the lotus pedestal his right foot steps on.

True to Lim's multicultural vision for an arts academy that serves South-east Asia, a region which shares a common heritage with India, Tang's painting makes a powerful point about Lim's foresight and aspirations.

It would be a great pity for Tang's larger-than-life installation to be stored away, once the exhibition at Nafa has ended, and for it to languish in a warehouse and be gradually forgotten.

It deserves to be installed in a proper place for public display or exhibited in an art museum.

In addition, just as we already have a road named after Brother McNally and another named after Zubir Said, who composed the national anthem Majulah Singapura, is it not time that we considered commemorating the enduring legacy of Lim Hak Tai by naming a road after him?

• The writer is former director of Art Retreat, incorporating the Wu Guanzhong Gallery.