For 2016 and beyond, Thailand will continue to face a reckoning at the end of an era that harks back more than half a century. It has proved itself a successful kingdom that now has to function like a workable democracy.

Until this daunting and existential challenge of reconciling kingdom and democracy is addressed by capable leadership and a collective will to compromise among the elite, with a new understanding between the elite and the masses, Thailand is likely to remain mired in its navel-gazing malaise indefinitely.

Understandably, much of the international spotlight on the Thai scene will be fixated on the military junta's road map for a return to democratic rule.

After it seized power in May 2014, the military government, led by Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, has bowed to international and domestic pressure by obliging to a timeframe to draft a new Constitution and allow elections to take place. But the first round of charter composition came to naught as the Constitution Drafting Committee and the National Reform Council, both junta-appointed, disagreed on its provisions.

The second charter attempt now tracks a 6-4-6-4-months-long schedule of drafting, organising a referendum, promulgating enabling laws and staging polls by mid-2017. However, if the second charter draft is voted down in Thailand's second-ever plebiscite (the first was also on a previous military-inspired charter in August 2007), it is unclear what the military government would do. It would come under pressure to resign but it will be tempted to ride out the storm and continue in power because its self-imposed interim Constitution indicates that the drafting process would have to start over again.

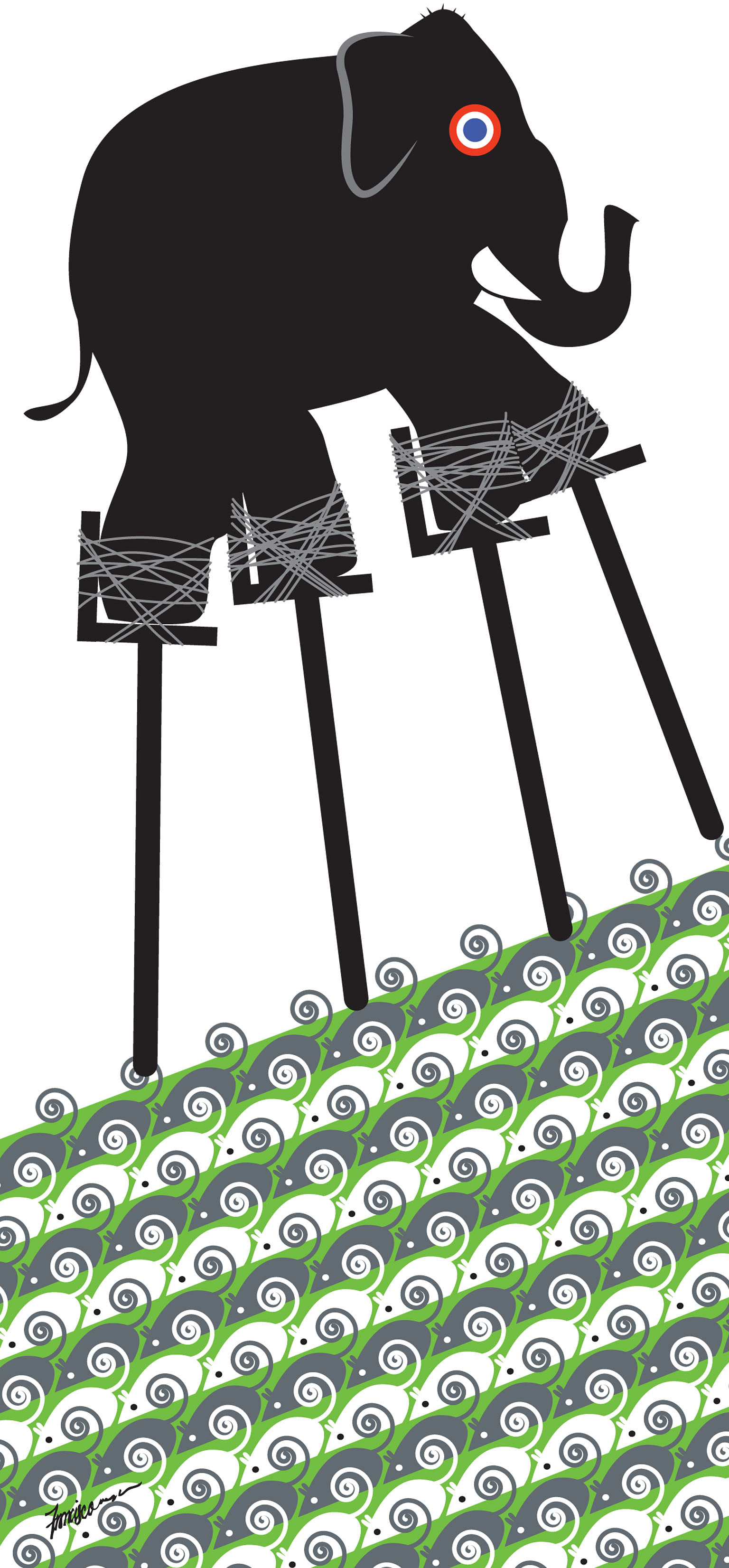

Like its precursor, the second charter draft prioritises the role of restraint over representation. Elected representatives are to face a wide array of checks from appointed committees and agencies. This will result in a lack of institutional balance between the executive and legislative branches on the one hand and other branches of authority - namely extra-parliamentary committees, the judiciary and the military-monarchy symbiosis - on the other.

Moreover, the Senate is set to be partially or wholly appointed by junta-influenced bodies, with considerable authority to hem in elected representatives of the Lower House. The draft charter also proposes that the post-election prime minister need not be an elected MP, which allows an outsider from the junta or its nominee of choice to rise to the top.

If these plans come to fruition, post-election Thailand would look like a "custodial" democracy under the longer-term influence of the junta and its coalition allies in the conservative establishment.

DISCREDITING DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS

What is more disconcerting from these controversial stipulations is the systematic, long-term discrediting of Thailand's democratic institutions.

The coup period and the charter-drafting process have resulted in the open demonisation of elected politicians as the primary source of Thailand's corruption and graft, while there are pledges to return Thailand to an electoral setting in due course. This approach is likely to lead to a dead end that will further complicate and exacerbate Thailand's political future.

If Thailand is to regain a democratic footing, then democratic institutions need to be restored and rebuilt, not deplored and downgraded.

True, Thai politicians are notorious for graft and abuse, but bureaucrats, business people and senior military and police officers are not far behind them. Reports of irregularities and kickbacks among these other groups of unscrupulous individuals regularly show up in segments of the Thai media that are still free, independent and outspoken.

For example, the recently retired commander-in-chief of the army has been embroiled in a corruption scandal involving the construction of Ratchapakdi Park, a public monument in the Hua Hin seaside resort that celebrates past great kings.

The park reeks of extortion, commissions and misallocated public funds now lining private pockets, but the several military-appointed committees invariably came up with exoneration, even though the justice minister (also a retired army general) conceded that graft took place.

While the scourge of corruption corrodes Thailand's political system, governance, bureaucratic machinery and social fabric like no other source, it should be tackled and rectified from a strengthened and accountable democratic polity, not used to undermine a democratic future.

CONSTITUTIONAL MACHINATIONS

Constitutional machinations will thus dominate the Thai scene for the coming year, marked by public controversy and acrimony. Despite its design flaws, the Thai electorate will both be pressured into passing the charter and incentivised to let it go through referendum in order to reach a polling stage next year.

Tension will thus rise as the constitutional clock ticks forward towards an election and a transfer of power from the military government. Yet the constitutional timetable is merely a sideshow in the broader Thai drama. What is at stake is Thailand's existential need to recalibrate and refit an established political order for the globalised and democratised era in the early 21st century. That order revolved around the military, monarchy and bureaucracy, the holy trinity that has ruled Thailand for nearly seven decades. It featured a strong, centralised authority that was enabled and nurtured by Cold War exigencies.

Many Thais are grateful for its efforts because Thailand never succumbed to communism like its neighbours. Not only that, the Thai economy also flourished from the stability and economic planning during the communist-fighting decades.

But these traditional institutions became an inevitable victim of their success as the Cold War ended and newer voices became empowered by expanding education, rising income, proliferating and affordable information and communications technology and changing international norms towards human rights and democracy.

Over the past decade, major external powers no longer countenanced Thai coups, unlike during the Cold War. The Thai electorate also became more conscious of their rights and stakes in the political system.

This profound juncture between the old order having to give way and a new democratic arrangement having to steer Thailand's way forward coincided with the rise of the ousted and exiled Thaksin Shinawatra and his cliquish rule.

While Thaksin was seen as abusive and prone to graft and collusion in recent years, the established centres of power have been unable and unwilling to come up with a democratic alternative to preserve some of their vested interests while making concessions to the newly empowered bottom rungs of society.

THE WAY FORWARD

Thailand's way forward has not changed over the past decade. It has to be a democratic way underpinned by a continuity that involves concessions and compromises between the established order and emergent institutions of popular rule in the run-up to and after the all-important royal succession, keeping the Thaksin political machinery at bay but incorporating the newly vested voices that he unwittingly unleashed.

As this wrenching process unfolds, the Thai economy will remain resilient but underperforming.

Thailand's economic cushion is immense but all shock absorbers eventually wear out. The biggest dilemma for the Thai people is thus how long it will take for their elites and leaders to get their act together and make the necessary adjustments so that their country will continue having both monarchy and democracy on a new horizon.

• The writer teaches international political economy and directs the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.