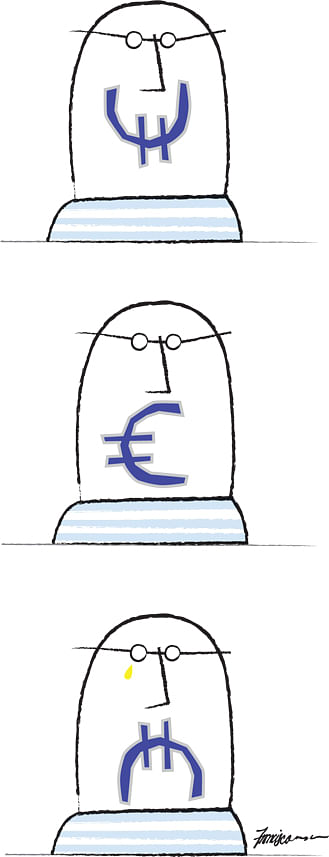

LONDON • Regardless of how the drama over Greece's bailout from financial bankruptcy concludes, there is no shortage of economists rushing to point out that Europe's currency arrangements were fundamentally flawed from the start and that what happened to Greece was entirely predictable.

As Professor Augustine Tan of the Singapore Management University argued on these pages only last week, the establishment of the euro as Europe's single currency "violated most of the requirements of an optimal currency area", and especially the requirement for a "fiscal union", a common system of collecting taxes and distributing revenues.

However, what such critics invariably fail to mention is that the flaws they allege to have discovered have been known since the euro was first conceived. European leaders still went ahead - not because they were economically illiterate but because they assumed that many of these flaws will be fixed as time went by. The real lesson from Europe's current trouble is not that currency unions must be perfectly designed but that governments must be vigilant in operating currency unions.

All of Europe's previous currency unions - and there were at least four attempts during the 19th century - were political projects masquerading as financial propositions. The euro was no different: it was mainly conceived to compensate for the largest strategic realignment in Europe's post-World War II history, namely the end of the continent's division and the re-emergence of Germany as Europe's single biggest power.

By depriving Germany of the use of its mighty deutschemark, the thought then was that Germany could be prevented from transforming economic influence into political supremacy.

The political fathers of the euro idea spared little thought to how the currency would work. But the Germans who embraced the concept saw it as a replica of their own historic experience, of the Zollverein, which started as a customs union between small German individual statelets during the 19th century, slowly to cement the united Germany we know today. The way European national banks operate the euro and the way member states are allowed to display their own national symbols on one side of their own minted euro coins were all concepts borrowed from Germany's historic currency-union experience.

Seen from this perspective, the absence of conditions which economists may consider as essential for the operation of a currency were not regarded by the fathers of the euro as insurmountable obstacles but more as inevitable opportunities for further European integration.

As then Chancellor Helmut Kohl said to the German Parliament in the early 1990s: "History teaches us that it is absurd to expect in the long run that you can maintain economic and monetary union without political union."

The expectation that a currency union will inevitably lead to a fiscal and political union may seem naïve now, but it was regarded once as imminent. The reason Britain insisted on negotiating its permanent opt-out from the whole euro project was precisely that it feared the spectre of one tax regime and one continent-wide budget. And precisely because European leaders were aware that they were putting the cart before the horse by creating a monetary union in anticipation of a political union, plenty of safeguards were wired into the system.

To ensure that a single monetary policy can work alongside budget policies decided by nation-states, the founders of the European monetary union drew up the fiscal rules enshrined in the so-called Maastricht Criteria and the Stability and Growth Pact, both of which impose clear limits on what individual European Union governments can do.

But the key point of these measures was not only to safeguard against excessive government debt; more important was the rule that EU member states remain fully responsible for the consequences of their own fiscal decisions. That's why the European treaties explicitly rule out the assumption of any member state's debt by the EU or by other member states, the so-called "no bailout" clause.

DEBT FORGIVENESS

Those who criticise the EU for failing to write off Greece's debts are, at best, ignorant of how the euro system operates. It is also depressing to see learned economists making facile comparisons between the way Germany itself obtained debt relief in 1953 after World War II and the demands for a similar debt write-down by Greece today. Not only were the circumstances completely different then, but the Germany of 1953 adopted an entirely new Constitution, overhauled its government and introduced a new currency before it obtained any debt forgiveness. Greece is offering none of these reforms.

Nor is it true that Europe is content to let countries rot in debt forever. As German politicians have repeatedly stated, once a fiscal union is established, debts could be shared by all the member states.

It's simply nonsense to blame the current crisis on Germany, although that may be comforting for fashionable left-wing economists, particularly those based in the United States.

Debt forgiveness without fiscal union is merely an invitation to more irresponsible behaviour. Refusing to contemplate it before a country such as Greece undertakes true reforms is the right way to defend the currency.

So, what actually did go wrong with the euro?

The first mistake committed was to ignore the stringent admission criteria and accept into the euro zone every country which wanted membership.

Greece may well have been the "cradle of European civilisation" but it was never that of good governance. The country is profoundly unmodernised, run by a deeply corrupt political elite which finances its rule by borrowing. Even a decade ago, Greece was spending more than 14 per cent of gross domestic product in excess of what it was producing, the largest such gap on the continent.

The problem is that Greece produces very little of what the world wants to consume. Greece's pretences to be a developed rich state are bogus, fuelled through borrowing. Refusing Greece admission to the euro was not only essential for the safety of the currency but also an act of charity to the Greeks themselves.

Yet having first failed to uphold their euro membership criteria, EU governments then went on to ignore their duty to police the currency rules. Ironically, the first countries to breach these rules were Germany and France, which, for a while, ran excessive deficits. In theory, that should have triggered a warning from the European Commission, followed by the imposition of fines. In practice, however, both Germany and France ignored the proceedings.

That was a catastrophic mistake, for it not only hurt Germany's ability to demand responsibility from others but also silenced the EU officials who were trying to ensure the application of the same rules to others. Far from becoming autocrats, those whose duty was to police the operation of the euro failed to even be good bureaucrats.

FAILURE OF IMAGINATION

And then, there was a lamentable failure to identify impending fiscal crises and nip them in the bud before they became unmanageable. It was obvious to all that fiscal policy was out of control in Greece: The country's overall debt stood at more than 120 per cent of GDP on Nov 15 , 2004, when a then Greek finance minister breezily admitted that his predecessors essentially falsified the national statistics.

Had EU leaders acted immediately, the readjustment Greece would have needed may have been less painful than today. But they didn't, and a subsequent admission a few years later by another Greek finance minister that his government continued to falsify statistics triggered the crisis Europe faces today.

Yet probably the biggest euro failure has been one of imagination - of not pushing through with the fiscal union everyone knew was a necessary complement to monetary union.

Too many politicians - Germans included - were content to hide behind slogans rather than action, a neglect for which Europe is now paying dearly.

None of this is to suggest that the euro is about to crack up or that the Europeans have lost their sense of solidarity. Investors should take heart from the fact that the battle remains one about the maintenance of a strong currency, and that the Europeans have been prepared to put up with a lot from Greece, a country which never returned as much European solidarity as it demanded from others.

Still, for regional organisations such as Asean or the Gulf Cooperation Organisation, both of which toyed in the past with the idea of introducing their own currency unions, the message from the euro crisis is pretty clear.

Currency unions should be viewed as evolving structures rather than beautifully formed projects from the start. Currency unions need not only solid foundations but also robust policing mechanisms. And currency unions cannot remain unscathed if the political impetus behind their creation is not maintained.

The fathers of the euro realised that their monetary union was a journey rather than a final destination. And so it remains today, despite Europe's Greece stumble.