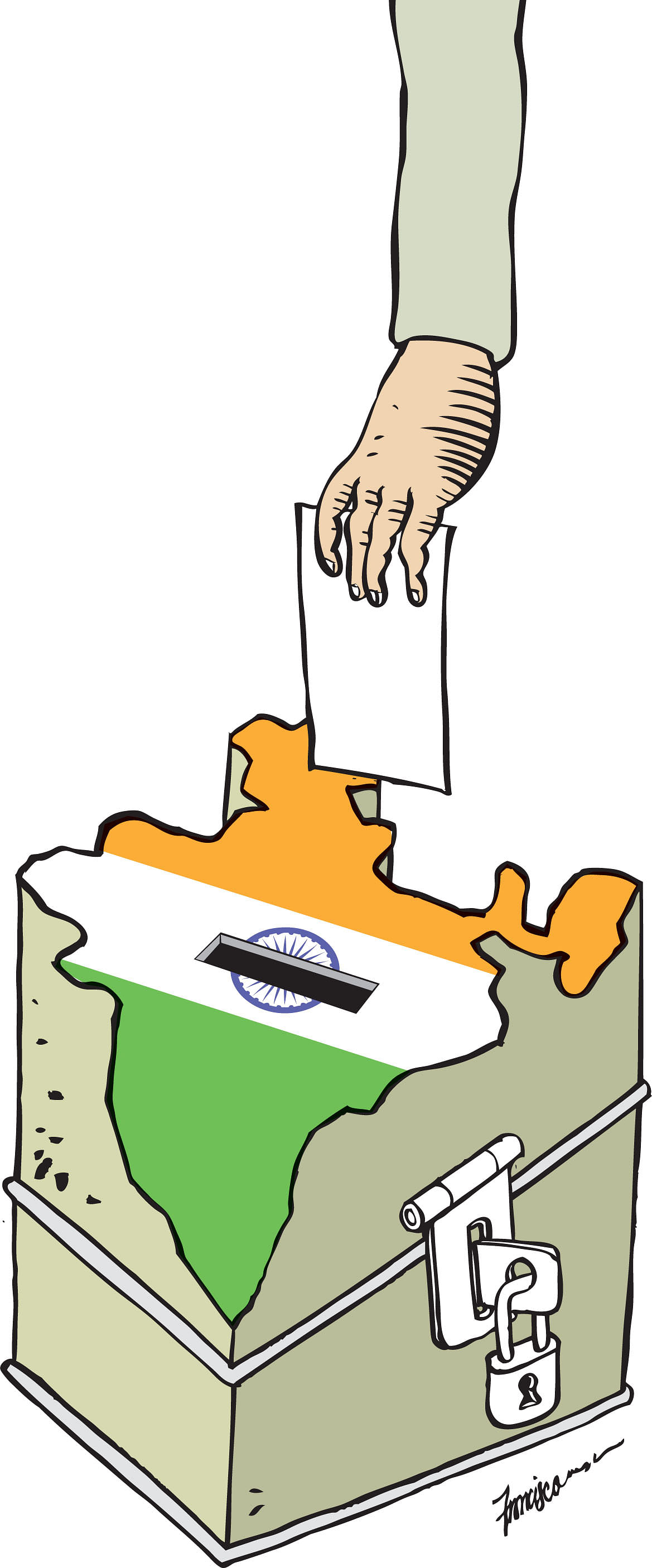

Amid all the excitement about new turns in Japanese politics ahead of this weekend's polls and speculation that Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak is poised to announce dates for his own re-election bid, it has largely gone unnoticed that the world's largest democracy has just slipped into election mode as well.

India's next general election is not due until the summer of 2019, but there is little question that the Narendra Modi government is already in campaign mode.

Immensely more decisive than his Malaysian counterpart, the speculation is that the hard-driving Mr Modi may surprise India by calling polls a year early.

The bad news for Asia is that it must now prepare to wait until the election cycle is completed before it can see any meaningful market-opening reform in Asia's No. 3 economy.

It had been patchy enough anyway. The India policy division at Washington's Centre for Strategic and International Studies recently calculated that of 30 key reforms planned when Mr Modi took charge, nine have been completed, 13 have been partly done and there has been no progress at all in eight.

Now, as he approaches key state polls and the national poll beyond, all sorts of demands are rising, including pressure on the government to go slow on signing on to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement, something of vital interest to South-east Asia.

Even in areas where he has progressed, Mr Modi has felt compelled to rein it in a bit.

Two weeks ago, speaking in his home state of Gujarat, Mr Modi swallowed his economic pride and announced cuts to the complicated goods and services tax (GST) imposed on several items, dramatically proclaiming it as "Deepavali come early" for Indians.

There are other straws in India's election winds. Last week, his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) flew down Yogi Adityanath - newly installed Chief Minister of populous Uttar Pradesh state and custodian of one of its most popular Hindu shrines - for rallies in southern India's Kerala state.

Ignoring the fact that Mr Adityanath's brand of Hindu nationalist politics is despised in Kerala - which got Christianity before Europe, and Islam along with its birth in the Middle East - party managers were clearly seeking to consolidate the Hindu vote there as they took on the ruling Marxists and their chief opponents, the Congress party. Meanwhile, India's opposition is losing its sense of despair, thanks to perceived vulnerabilities that have opened up in the persona and politics of Mr Modi, who had seemed all but certain to dominate the country for at least another decade.

TAXING TIMES

Two ministers in previous BJP governments have ignored the awe Mr Modi inspires within party ranks to take repeated potshots at him. While it is widely acknowledged that both men are smarting over being ignored for ministerial office by Mr Modi, they have delighted the scattered opposition and a national media that, uncharacteristically for its instincts, tends to treat the prime minister with kid gloves.

Some of Mr Modi's vulnerability is due to the battering India is taking on the economic front.

The International Monetary Fund has trimmed India's growth forecast for this year and the next as the US$2.3 trillion (S$3.1 trillion) economy slowed from a canter to a wheeze in the last six quarters.

Also weighing on his appeal is the pain from July's implementation of the nationwide GST, a long-planned tax reform that has successfully converted India into a common market. India's complexity-loving bureaucrats worked in multiple slabs for even parts of a single product-frames and lenses in eyeglasses are taxed at different rates, to cite but one instance.

This has been not only extremely vexing for businesses but also crimped the generous profits the trading classes were used to earning, because of the system's enhanced tax transparency.

As GST finds its intended target in a cleaner economy - something which all Indian politicians have publicly claimed they aspire to but few had the courage to go for until Mr Modi implemented it - disaffection is spreading in the BJP's traditional vote bank of urban business and trading classes.

GST was pushed through even as India is yet to recover from the ruinous consequences of last November's sudden cancellation of high-value currency notes to unearth hidden and unaccounted stashes, delivering what Americans would call a double whammy.

The "demonetisation" sucked the air out of the cash-fuelled Indian economy, particularly in the hinterland. And because it came alongside a parallel force in urban India - the rapid march of automation - the result has been hundreds of thousands of jobs lost, and not enough new ones created.

All this has robbed Mr Modi of a bit of his swagger and reputation as a competent economic manager who gained global fame for turning his home state, Gujarat, into a manufacturing hub and the "Guangdong of India".

BEST BET

Still, demonetisation, while it hurt, gave Mr Modi a political windfall when his party swept the state elections in Uttar Pradesh early this year because of the perception that the move was aimed at the robber barons.

Uttar Pradesh is the country's most vote-rich province and one that has produced more prime ministers than all other states combined. In the 2014 parliamentary poll, the BJP's "Modi wave" saw it sweeping all but nine of the 80 seats from the province.

But that electoral showing is now seen as a one-off gain. The easy money now is reckoned to be on betting against Mr Modi in the next polls. Indeed, this column itself has pointed to Mr Modi's personality quirks and their impact on India (Is "go-it-alone Modi" hurting India?; June 16), and has previously noted that it will be near impossible for him to repeat the stunning landslide he engineered in May 2014.

A key political windsock is the upcoming state polls in Gujarat, which he has visited no less than seven times this year. Once a Congress party bastion, the state has been taken in 1995 by the BJP, which has retained it since. Congress vice-president Rahul Gandhi, who is likely to lead an opposition coalition, has been gathering crowds in his public contacts.

Two other large states - Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh -are also due to elect fresh state assemblies before the end of next year. Unlike Gujarat, these two have fresh new Congress faces to project as potential chief ministers in Mr Sachin Pilot and Mr Jyotiraditya Scindia, both of whom served in the last Congress government led by Dr Manmohan Singh. Clean, competent, forward-looking and untouched by scandal, they could, should the Congress overcome its fixation on the Gandhi family, be projected as viable leaders with big futures ahead of them.

Besides, they could help neutralise the Modi effect, which is based on precisely those attributes, plus a perception that as one who lives the life of a bachelor and renunciate, Mr Modi is somehow cut from higher moral cloth.

The three states account for 80 parliamentary seats. In 2014, BJP won 78 of them, sweeping all the seats in Rajasthan and Gujarat, and all but two of the 29 parliamentary seats from Madhya Pradesh.

Likewise, in Uttar Pradesh, which alone sends 80 MPs to the Lower House of Parliament, BJP won 71 seats with 42 per cent of the vote. But the next three parties together polled some 47 per cent in Uttar Pradesh and should they manage to present a united front, as they are attempting to, BJP could be vulnerable.

Yet it is too early to make the call on a Modi sunset. Mr Modi's firm hand - no major corruption scandal has broken in his time - and his acknowledged developmental agenda are undoubtedly still a draw.

On the other hand, Mr Gandhi has drawn crowds before, only to see that curiosity about him not translating into votes.

The economy, too, is stirring to life, perhaps just at the right time. Exports grew 26 per cent last month, the fastest in six months.

Capital goods output is growing again after four months of contraction. Industrial production has returned to its pre-GST trend growth of about 4 per cent, and foreign direct investment flows crossed US$8 billion in August and are heading for the US$100 billion-a-year mark.

There are other aspects of the Modi government that have passed unnoticed. I did a recent count of women with full Cabinet rank and it ran to no fewer than six, including the ministers of defence, external affairs, and information and broadcasting. Compare that with the sparse pickings in, say, Japan.

Aside from his often troublesome politics that tends to often reach for the easy route of majoritarianism, Mr Modi is perhaps India's best bet yet.

A reduced parliamentary showing for him may not be such a bad thing after all for India, especially if it could compel him to reach for coalition partners who could temper some of the flintier edges of his personality.