LONDON • Easter has come early this year for Christian believers belonging to Western churches, yet it will be very late for those in the Eastern Church, who will celebrate the feast of the Resurrection of Christ only on May 1.

But this unusually long time lag between the two branches of Christianity is mirrored in another, and this time ominous, development: growing evidence that Russia, which sees itself as the bastion of the Eastern Orthodox Church and traditions, now also views itself as engaged in an implacable and broader confrontation with the West.

The driver for this looming clash is not religion as such, or specific disputes over Ukraine or Syria. Instead, what we are witnessing is a deepening gulf between Russia and Western nations, driven by a newly-emerging Russian ideology which views the world in a fundamentally different way. A confrontation between Russia and the West, recalling that which fuelled the Cold War is, therefore, very much on the cards. And it could be just as long-lasting as the one which scarred Europe during the second half of the past century.

It's worth recalling that, despite his legendary mistrust of the West, Russian President Vladimir Putin did not start his political career as either an ideologue or as a nostalgic for the old Soviet Union empire. Shortly before he came to power in December 1999, he declared that he was "against the restoration of official state ideology in any form in Russia".

And although Mr Putin frequently reiterated his belief that the old Soviet Union should be credited with "some unquestionable achievements", he rejected the idea that this could be interpreted as either nostalgia for the past or an attempt to resurrect the old empire.

For, as Mr Putin explained, "those who do not regret the downfall of the Soviet Union have no heart, and those who want to bring it back have no head". And there is little doubt Mr Putin meant what he said at that time. He had no desire to mortgage his future by futile attempts to recreate the past.

Instead, what Mr Putin offered Russians at home was an implicit new contract: less personal freedoms in return for more stability and a steadily rising standard of living. It was, in essence, the same sort of deal China's rulers offered their people, with the difference that Russians did not even pretend to pay lip service to ideology, as China's government still does.

And to foreign governments, President Putin also offered a similar value-free bargain: Russia would no longer be automatically friendly to the West but it won't be automatically anti-West either. It will be ready to cooperate if Russia's own interests required it.

A NEW RUSSIAN IDEOLOGY

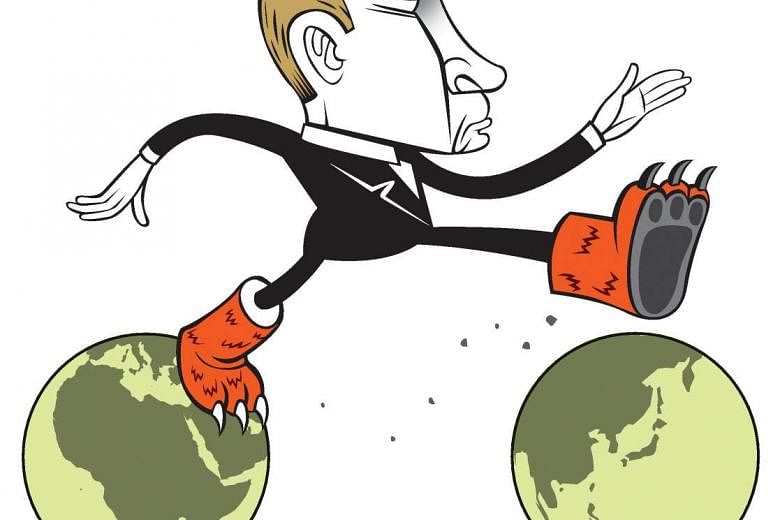

Over the last few years, however, Mr Putin and his associates have begun to construct a new state ideology. Its fundamental starting point is the assumption that the world represents a zero-sum game, in which winners take all the spoils, and Russia is either fated to triumph or be trampled underfoot.

According to Mr Putin's ideology Russians must reckon with unremitting hostility from a world in which, as he put it, few "want to deal with an independent and strong Russia that is confident in itself". Confrontation, and primarily with Western nations, is not only a matter of choice; it's a matter of necessity, one which is pre-ordained.

Equally pre-ordained is another idea, that of Russia's "sovereign democracy", a concept invented by President Putin's closest adviser, Mr Vladislav Surkov. Stripped of its niceties, all that "sovereign democracy" means is that whatever Mr Putin does at home is, almost by definition, justified as Russia's particular interpretation of democracy, and is not a topic on which Moscow will accept any criticism.

Yet probably the most interesting development is the slow ideological move away from describing Russia as a purely European country. Previous generations of intellectuals and politicians in both the Soviet Union and Russia have regarded their country's European identity as a given. Even Mr Putin once said: "The Russian people always felt itself part of the great European family and was bound to it by common cultural, moral and spiritual values."

Now, however, Mr Putin and his associates are no longer so sure, for they emphasise instead Russia as a "Eurasian" country, a supposed bridge between Asia and Europe.

One element of this has been the embrace of Orthodox Christianity as the official national faith. That's not necessarily because Russia's current leaders are pious - few ever see the inside of a church, and none conduct themselves as monks.

Furthermore, many of Russia's official ceremonials are now a bizarre combination of communist kitsch with religious fripperies. At military parades, for instance, hammer-and-sickle flags mix with religious icons, and Russia's defence minister crosses himself first before greeting his "comrade soldiers".

To all intents and purposes, Russia's love of religion is a purely political enterprise. It is intended to emphasise how different the country is from the rest of Europe.

And it also serves as a basis for a fake officially sanctioned morality play. Russia's virulent campaign against gays aims to portray the West as morally decadent, something which not only cannot act as a model for emulation, but must be actively opposed by every "morally upright" Russian.

THE RISE OF IVAN ILYIN

Another element in this growing trend of portraying Russia as distinct from all its neighbours comes in the officially sponsored cult for Ivan Ilyin, hitherto a virtually unknown Russian philosopher who was expelled from the Soviet Union during the 1920s and died in obscurity in exile. That Ilyin ended up praising fascism and turned into an incurable anti-Semite is not regarded as important by Russia's present leaders as the fact that Ilyin prophesied that Russia will be dismembered by the West by using ideas such as "democratisation" or "freedom", and that Russia's only "salvation" lies in establishing a strong authoritarian rule at home, while emphasising its supposedly unique geo-historic identity.

President Putin recently ordered all the country's regional governors to read Ivan Ilyin's book. Last year, when Russia celebrated Mr Putin's decade and a half as leader, one of the key achievements of his rule highlighted by official sources was the fact that he repatriated the remains of Ilyin for burial on home soil. Reinternments are a traditional Russian technique of reinventing history.

And in an astonishingly frank article published recently by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in his country's official diplomatic publication, Moscow confirmed its hostility to the West. Claiming that Russia is being subjected to "many diverse ways of exerting pressure", including "large-scale information wars", the head of Russian diplomacy spoke approvingly about a period centuries ago when "not a single cannon in Europe could be fired without our consent", and yet again quoted Ilyin, the "rediscovered" philosopher, who urged Russia to "take on the burden of great world problems", a more polite way of saying that Russia should resume the role of a superpower last exercised by the Soviet Union.

There are probably more than just one explanation as to why President Putin and his associates have chosen to discard their previous reticence and decided to forge a new ideology to define their regime and its policies.

The current economic downturn in Russia, brought about by low oil prices and Western economic sanctions, may be one reason - the Russian government has to find an explanation as to why its people are now suffering. Mr Putin may also have concluded that conducting politics without any guiding ideology of any kind created a dangerous gap in Russia's public life which needed to be filled.

And there is no denying the fact that many of the country's leaders believe they are facing unremitting hostility from the West, so Russia's current official ideology and foreign policy posture do represent geopolitical realities, as seen from Moscow.

But the result is that those who hoped that the downturn in Russia's relations with the West, as a result of the crisis over Ukraine, was merely an aberration, and Moscow and the West could join hands again in cooperation were proven wrong. For the gulf between Russia and the West now looks deeper than ever before.

And it appears just as irreconcilable as the millennium-old schism between the Eastern and Western strands of Christianity, which led to today's huge gap in the timing of the Easter celebrations.