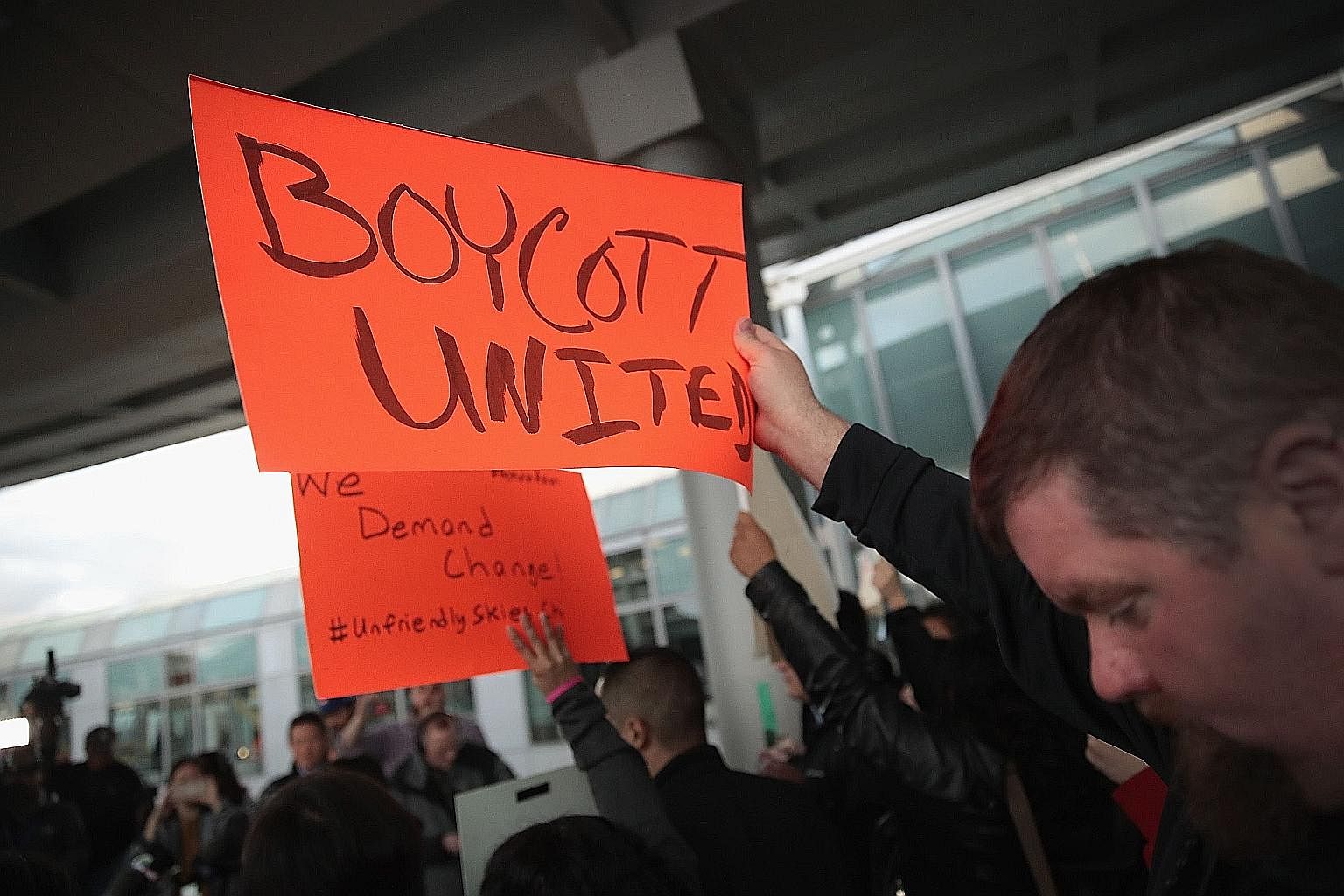

The recent dramatic eviction of a passenger from a United Airlines flight in the United States has prompted debate in Singapore on the common industry practice of overbooking, and raised concerns whether consumer rights are adequately protected.

While the economic benefits of flight overbooking to airlines are obvious - to ensure that the number of vacant seats is kept to a minimum and, thereby, maximise the revenue for each flight - the heart of the matter is how airlines exercise their discretion to "bump off" passengers.

Currently, there is no legislative framework in Singapore which governs the exercise of such discretion. In contrast, European Union Regulation 261/2004, enacted in 2004 to protect passenger rights, requires airlines "to reduce the number of passengers denied boarding against their will" by calling for volunteers to surrender their reservations, in exchange for compensation that is prescribed in these regulations. If there are insufficient volunteers, the airline may then proceed to deny boarding to passengers against their will.

A similar regime is found in the US Code of Federal Regulations, which requires an airline to request volunteers before denying boarding. A volunteer is defined as someone who "willingly accepts the carrier's offer of compensation, in any amount", in exchange for giving up the seat. If there are insufficient volunteers, the airline can deny boarding to other passengers "in accordance with its particular boarding priority", subject to compensation.

An airline's boarding priority rules are, however, no guarantee that a bumped-off passenger has been treated fairly. For example, in a lawsuit brought by the well-known American consumer advocate Ralph Nader against Allegheny Airlines in the early 1970s, the defendant airline had bumped off Mr Nader, who was due to give a speech to a public advocacy group, from one of its flights which had been overbooked. Mr Nader alleged that the defendant had contravened a provision in the US Federal Aviation Act, which prohibited an air carrier from subjecting passengers to unjust discrimination, or undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage.

Under the defendant's boarding priority rules, passengers with an "OK" marking on their tickets, or whose names were on a computerised list, had confirmed reservations and were to be boarded. After the flight had been boarded to capacity, Mr Nader, who had a confirmed reservation, arrived late at the boarding gate. He was not permitted to board as he was considered an "oversold" passenger under the boarding priority rules. The US court, however, found that the defendant had failed to comply with its own boarding priority rules, as it had denied Mr Nader's boarding priority by allowing at least one other oversold but lower-priority passenger, to board the flight.

Admittedly, notwithstanding the absence of a legislative framework in Singapore, it may well be industry practice for air carriers departing from Singapore to adopt the approach in Europe and the US - ask for volunteers first, then deny boarding. However, such a practice is likely to result in inefficient negotiations, as the passenger cannot be certain about the amount of compensation the airline is willing to offer in exchange for denial of boarding, which would not be the case if clear compensation laws were in place, as in Europe and the US.

Moreover, if this practice is applied inconsistently, both the airline and the passenger would be effectively negotiating in the dark about each other's positions. Coupled with the relatively tight timeframe that such negotiations must be completed before take-off and the potential permutations of each airline's boarding priority rules, one would expect that complaints against overbooking would be regularly lodged with the Consumers Association of Singapore (Case). However, following the United Airlines debacle, Case was cited in a media report as stating that no complaints against overbooking had been lodged since January last year.

One plausible reason that may explain the apparent gap between theory and reality in Singapore is that because overbooking is a long-established practice, airlines have become adept at resolving the impasse if no volunteers step forward initially. As mentioned in The Sunday Times report on April 16 (No Room On The Plane), airlines may simply increase the incentives for denial of boarding. Also, given the large pool of potential "volunteers" available, it should not be too difficult to find a few passengers who are willing to be bumped off in exchange for adequate compensation. Compensated passengers are unlikely to be motivated to make a complaint to Case even though their negotiations with the airline may have taken more time and effort than necessary. Unless one is forced off the plane involuntarily, as in the United Airlines incident, there would not be clear cause for complaint.

Nevertheless, the absence of consumer complaints may not be conclusive evidence that the market is working efficiently and no legislative intervention is required. Where there is poor management of oversold seats, the authorities must step in to achieve a better balance between the interests of passengers and those of airlines, and promote better customer-handling procedures.

One area of concern is whether airlines should be permitted to deny boarding to vulnerable passengers, such as the elderly or the illiterate, on the basis that they had agreed to compensation. Such consumers may, however, not have understood the full ramifications of being denied boarding or appreciated the adequacy of the compensation offered. Under the US Code of Federal Regulations, it may be arguable whether they would be considered volunteers if their "willingness" to accept compensation was procured by improper influence. The lack of statutory guidance in Singapore on how airlines should exercise their discretion to bump off passengers may result in arbitrary or, worse, unlawful decisions, which should not be shielded by the "defence" of industry practice.

In the interest of consumer protection in Singapore, clear provisions on the procedure for denying boarding and compensation amounts should be set out in statute, so as to address the information gap faced by passengers. Airlines should also be obligated to inform passengers of their rights to compensation and assistance, similar to those set out in Article 14 of EU Regulation 261/2004. Treating passengers fairly would not only be consistent with the position in Europe and the US, but would also reinforce Singapore's reputation as one of the world's top air hubs.

•Mr Tan Chong Huat is managing partner and Mr Alvin Chen is general counsel, legal and compliance, at RHTLaw Taylor Wessing.