We tried to guess where she had come from. Her surname, Tsang, is rare in Singapore. Her Chinese name is Wei Wen; the character wen means "culture". Mostly, we call her Vivian. She is in her 60s, but looks younger with her fierce eyes, sharp nose, chiselled chin, fair skin, and gray hair dyed auburn. She speaks eight languages. How did she end up finding home here?

A while ago, Vivian hadn't realised her years have added up to a story. There had been so much living to do, so little time to tell. Now she begins to tell it, even though she thinks it's an unimportant history; just life, you know?

As a young boy in China, Vivian's maternal grandfather, New Shu Chun, got a radical haircut. His pigtail, symbolising subordination to the Qing emperor, was snipped off. It was 1912. He witnessed the fall of China's last dynasty. He took to Christianity, the religion of the foreigners. He joined the Kuomintang (KMT), led by the Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen. He secretly studied English. He was a man ahead of his time.

Because Grandpa New could speak English, he became one of China's first consuls to Nanyang - that mysterious archipelago down south. It was the late 1940s. Vivian and her family followed and set sail for days. From Shanghai to Jakarta, they sailed. It was like that hit song at the time, Slow Boat To China, except they took a slow boat from China.

I'd like to get you on a slow boat to China

All to myself alone

Get you and keep you in my arms evermore

Leave all your lovers weeping on the faraway shore

Lovers did weep. The Chinese civil war was at its height. A little more than a decade after, the Cultural Revolution began. Forced by Mao Zedong's officials, one of Vivian's relatives sprinkled vitamins into his own family's tea. He found out, far too late, that it was pesticide. Vivian sighs. "In 60s China," she says, "there was no such thing as lovers or family."

She would be far from these horrors. Yet Nanyang had its own troubles. Grandpa New's consular office opened in Yogyakarta in 1947, right in the middle of the Indonesian Revolution.

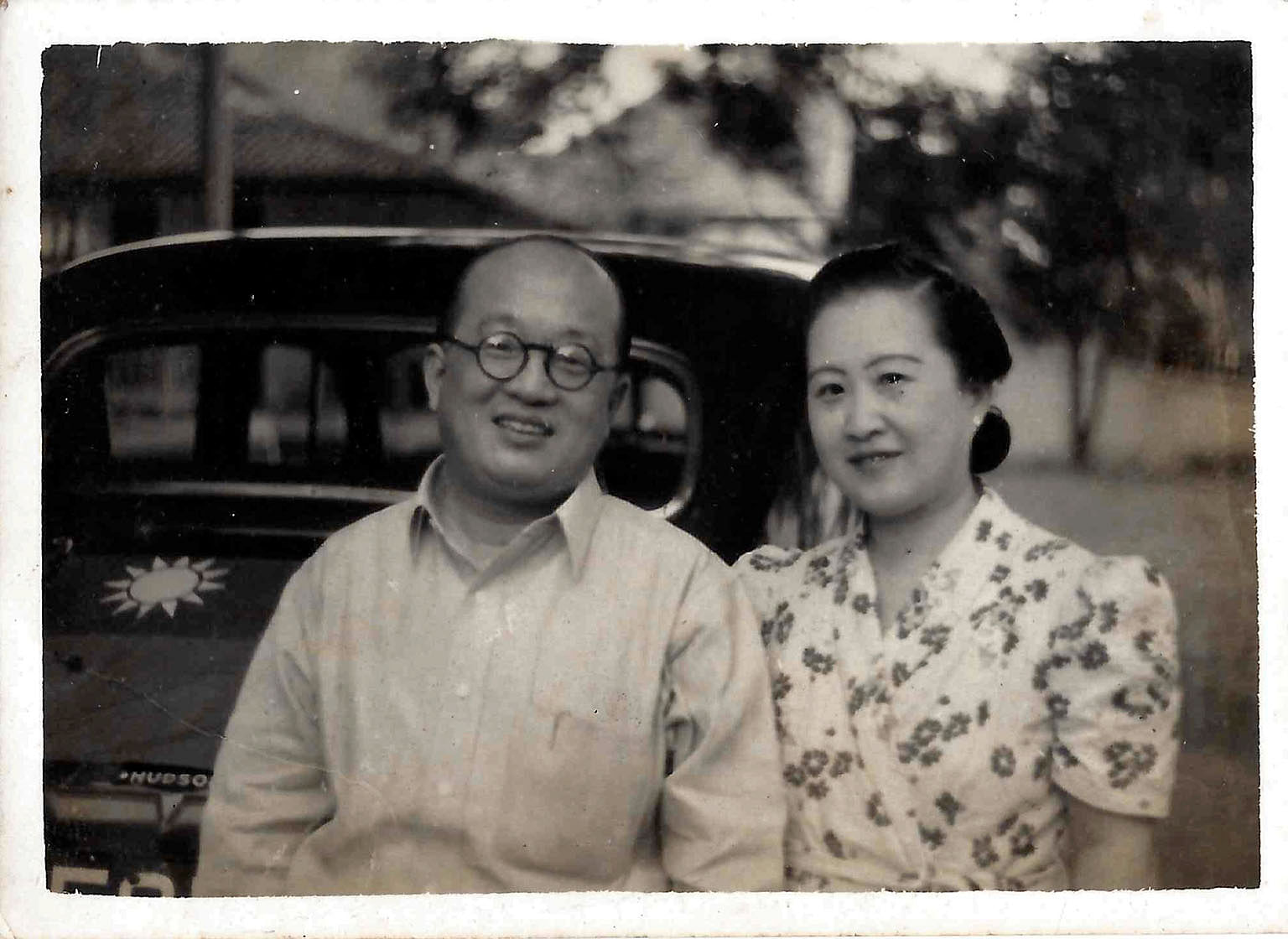

Vivian has a photograph of Vice-Consul New in a meeting with President Sukarno. We imagine them discussing the ethnic Chinese: how the minority group wanted a voice in Nanyang; how they sought to set up businesses; how they feared the inter-ethnic violence; how they debated dual citizenship. Their own backyard a mess, the Chinese were finding their place in the world. Nanyang was opportunity. There, on Vice-Consul New's shoulders, was that invisible weight of hope.

I try to figure out his facial features from the photograph. The camera flash had whitewashed Vice-Consul New's face, as if predicting his place in history. A year after the picture was taken, in 1949, Sukarno led the Indonesian Revolution to its end.

Up north, the KMT lost Beijing to the Communist Party. Overnight, Indonesia aligned itself with the latter. At his Jakarta bungalow, Grandpa New heard a knock on his door. He opened it. He was asked to pack up. He was gone.

-

WONG SHU YUN

-

Wong Shu Yun is a writer focusing on narrative non-fiction. She is working on Small City, Big Dreams, a collection of stories that explores Singapore's coming of age in a post-Lee Kuan Yew era. Ode to Slow Boats is adapted from it.

THREE NOTABLE WORKS

Short Stories

Wong's short stories are in various anthologies including The Epigram Books Collection of Best New Singaporean Short Stories: Volume Two (Epigram Books 2015) and Passages: Stories Of Unspoken Journeys (Ethos Books 2013).

Do You Fear The Line? (Math Paper Press 2011)

In 2008, Wong witnessed the hopes and dreams of Nepal as it turned from a monarchy to a republic. This chapbook documents her memories as a reporter there.

Heart Of Public Service: Our People (Public Service Division 2015)

For the Heart Of Public Service book-set, Wong co-authored the People volume, which features the life and times of more than 50 individuals from the Singapore Public Service.

Vivian was barely five. She was taking a different slow boat this time. "Off to Pulau Onrust for picnic with hor tia," she recalls. Hor tia means "good father"; there is no Shanghainese word for "grand". Her parents hadn't told her that good father was now an exile - a man in the wrong place at the wrong time. There is a footnote about Grandpa New in a history article - his address to Chinese refugees in Yogyakarta. He said: "With regard to citizenship, it is up to the Chinese people (in Indonesia) to choose, but whatever (their choice) and wherever (they are), Chinese people are always Chinese."

Grandpa New didn't know that he would be stripped of choice: neither communist China nor Indonesia wanted a KMT official and his family for citizens. They would be stateless for 20 years.

As a young girl in Jakarta, Vivian picked up Bahasa Indonesia. Besok mau ke sekolah! Tomorrow, to school! At Regina Pacis, the only English primary school in the country, Vivian often bumped into Sukarno's daughter Nina, who had a sassy ponytail. Later, Vivian discovered Nina's real name: Megawati. At Regina Pacis, a nun spoke in French. Vivian was intrigued by the sound of it. She yearned to study French. Her parents asked, "What do you want to do with it?" She didn't know. That's life; c'est la vie.

Her father worked for the United Malayan Banking Corporation Berhad. This took the family to Hong Kong. Vivian quickly learnt manners in Cantonese: "Sik bao mei ya?" It means, Have you eaten?, which is another way of saying, How are you?

Her father's work also took them to Singapore. As stateless people, she and her siblings attended private schools. They travelled with Certificates of Identity (CI) - issued from Hong Kong - that read: To be used in lieu of a passport.

At 18, Vivian hopped onto an American President Lines. Gliding across the Pacific Ocean, from Hong Kong to America, she made friends on board, hoping she would see them again in the new land. She didn't. She arrived in San Francisco, at the California Baptist College. She would major in French and minor in - "Me llamo Vivian!" - Spanish. Language opened worlds. "It's also geography, history, culture," she says.

But these worlds weren't always welcoming. Once, she headed to France for an attachment programme. At the airport, she learnt about shame: first, you had to take that nervous walk to the immigration officer; then you bargain, paying that emotional price of not belonging anywhere, your CI a useless piece of paper; and still, all that isn't enough. No passport? No stamp. No go.

You turn away; in your return, you are already a different person.

Eventually, Grandpa New was given a choice: stay in Pulau Onrust or sail out of Indonesia. He ended up in Brazil with relatives. The country needed people to set up businesses. It would be a temporary home; hor tia never belonged.

Meanwhile, Vivian's parents stayed in Singapore, where her father continued to work in banks. After the family received permanent residence status, Vivian's mother wrote a letter in Chinese to the minister-in-charge, seeking permission for hor tia to live here. Hor tia made Singapore his final home, where he died in 1978.

At this time, Vivian returned to Singapore from America. She applied to be an English language lecturer at Ngee Ann College. In 1979, Singapore launched the Speak Mandarin Campaign, an effort to replace the use of Chinese dialects with Mandarin and hone the nation's bilingual education policy. Vivian was in the right place at the right time. She became a Singaporean.

"I suppose home is Singapore," she says, not sounding absolutely sure, for, what is home? A place we will ourselves to choose; the passage of time that, like a current beneath a boat, moves us on and on with the force of the past; a myth realised after the struggle? The question of home binds us all - makes us reach out to another when familiar soil breaks apart, or when we find ourselves, constantly, on different soils.

The college sent Vivian to Germany in 1992. Singapore was industrialising and desperate to speak with the German engineering sector. She studied the language furiously. A single word could run 500 miles long, she jokes. Even ordering dessert was hard: "Schwarzwälderkirschtorte!" Literally, "Blackforestcherrytart!" "Learning a language for survival or teaching is so different from learning it as an interest," she says.

Now she could answer her parents. What would she do with studying languages? She would teach.

This was how we met.

In speech class, she taught us that flour is pronounced "flou-er". And then, she mischievously added, it is better to "flah" with the FairPrice supermarket aunties. We learnt to code-switch: we could say "ah-mond" so the world would understand us, or we could say "al-mond" out of habit so our families would understand us. Vivian reminded us that language is communication and on a deeper level, connection.

These days, she thinks in Shanghainese, counts in Mandarin and speaks in English and Bahasa Indonesia. Still, there is a language closer to her than any other. The one not learnt, but felt; not spoken, but sung. It is music.

As a young boy in China, Vivian's father used to tinker with the radio. One day, the rapturous waves of Western classical music rolled into the cool, Chinese air. He fell in love. When she was growing up, she, too, listened. She, too, fell in love. She talks about Beethoven's Symphony No. 9. In the composition's final movement, Friedrich Schiller's Ode To Joy is sung.

She knows the words by heart. Freude, schöner Götterfunken... Joy, beautiful spark of divinity… She fills the hall with her full voice. She feels at home in song, like taking a slow boat to nowhere.