In the Ramayana epic so popular as a dance form across South-east Asia, the god-king Rama's staunchest ally in battle is Hanuman, a creature of extraordinary strength and heroic initiative.

But what if Rama, weary of overseas campaigns, abdicated his responsibilities and left it all to his sidekick to continue the good fight?

Something of that nature took place last week on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) forum in Vietnam when, thanks to the diplomatic heavy lifting of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, America's closest Asian ally, 11 nations of the Pacific Rim agreed to the rump trade deal of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, called CPTPP. The abbreviation expands as Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for TPP.

The critical element of CPTPP is that it omits the US, which pulled out of the TPP on President Donald Trump's first day in office, thus yanking out two-thirds of the combined gross domestic product of the original TPP twelve.

From 40 per cent of global GDP, the new trade deal covers about 14 per cent, even though it involves the livelihoods of 500 million people. In short, this is Ramayana without Rama.

Why is Mr Abe so fervently playing the keen shepherd? There is perhaps more than one motive.

To begin with, getting this far needed Herculean efforts on the part of all participants, given the complicated nature of the TPP with its interlocking chapters, and high levels of ambition. Every country needed to tackle domestic opposition to some or the other provisions in the deal that hurt a variety of interest groups - indeed, if Japan's internal struggles had been resolved earlier, TPP, with the US included, may even have become a reality while President Barack Obama was still in office.

Second, getting TPP, or CPTPP, implemented is crucial for Mr Abe's domestic reform agenda. As entrenched as he is domestically, with an overwhelming mandate to govern, Mr Abe is compelled to make haste slowly.

That holds whether in moving on structural reforms, the third arrow of his Abenomics - seen as a priority for keeping growth ticking over at 2 per cent of GDP for the next decade - or making the constitutional changes required to give Japan a normal military, one that can also come to the aid of its allies if required. A corollary to this is a military industrial complex that can export arms freely.

It is a tactic perfected by some politicians who have to operate in robust democratic systems - India's late prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, and his successor Atal Bihari Vajpayee were past masters at it - sign first, then order your bureaucrats to frame the necessary changes, citing solemn national commitments!

But there is an important geostrategic element as well; TPP, though sired by the vision of Singapore and New Zealand, had evolved into something larger. Its prescriptions on curtailing state-owned enterprises (SOEs), for instance, were written not just to favour the interests of private industry but also with a clear eye on China.

Since Beijing is in no position currently to yield on SOEs, nor likely to be for at least another decade, all the benefits that accrue from TPP would have reached the signatories bypassing China.

For countries like Vietnam, which are deeply concerned about their overwhelming dependence on China for economic growth, CPTPP is additionally an opportunity to get growth from a wider basket.

Interestingly, one way or the other, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines have all expressed interest. At a time when China is moving swiftly on its Belt and Road Initiative, the signal has gone out loud and clear that BRI is not the only game in town.

Not for nothing is it said that in Asia, trade is strategy.

The big takeaway from CPTPP, and Mr Abe must be thanked for it, is that globalisation is alive and well. Suddenly, Mr Abe - not China's President Xi Jinping - seems cast in the cheer-leading role. The timing is impeccable: According to the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council annual survey of opinion leaders, rising protectionism is considered the top risk to growth in the Asia-Pacific region.

Still, CPTPP, while laudable, does hold back on some vital issues compared with its parent. A priority sector would be intellectual property rights - but these largely were items written into TPP specifically to keep the US on board and are now carrots to be dangled for a future US president to bring his country back into its fold.

Indeed, Mr Trump is poised to soon be made aware of the ramifications of his folly as Australian beef exports to Japan crowd out US beef, thanks to Canberra's access to the trans-Pacific deal.

CPTPP also involves labour and environmental standards, bans on human trafficking, child labour and support for labour unions - stuff not part of the negotiations on most free trade agreements. These are some of the reasons why it is often referred to as a "high quality" trade deal.

While the optimists hope that the deal can be signed, sealed and delivered by the middle of next year, the realistic expectation is for CPTPP to be concluded in early 2019.

Unlike the TPP, which required ratification by members accounting for 85 per cent of the grouping's total GDP - the US and Japan for short - the CPTPP requires assent by only a simple majority. That means once any six of the 11 give their assent, it can pass into law.

For the four Asean states in CPTPP - Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei and Vietnam - this is like an Asean Economic Community in fast forward since, between themselves, they can supply almost all sectors and invest without limits, avoiding the need to look for local partners. In a sense, the four have now leapfrogged Asean.

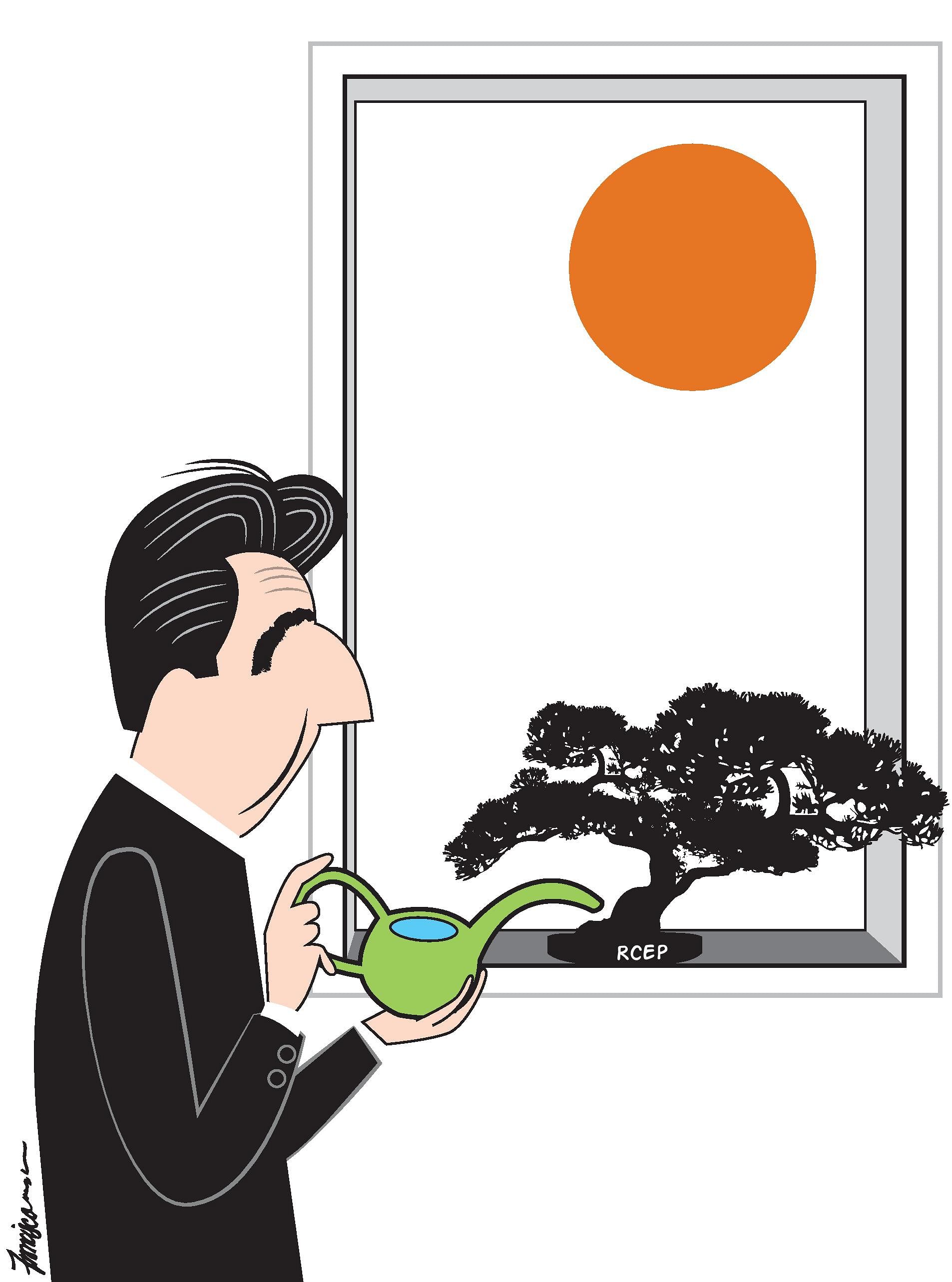

With CPTPP in the bag, as it were, attention will swivel to the slow-moving talks to stitch a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), an Asean-led initiative that seeks to bring into its fold China, Japan, India and South Korea - the four economic giants of Asia plus Australia and New Zealand.

While RCEP ministers held their first summit in Manila recently, progress towards that agreement has been less than satisfactory despite 20 rounds of talks. The bulk of the agreement, including fixing the levels of market access, has yet to be firmed up.

One of the trickiest issues is India's demand that any "comprehensive" pact should also include liberalisation of trade in services, the area in which it feels its economy has a competitive edge. Other RCEP members have difficulty accepting this because of domestic political sensitivities.

Another tricky issue in RCEP that CPTPP nations managed to overcome is opening up agriculture.

Strategic suspicions of China, which is sometimes erroneously described as the moving force behind RCEP, is a big factor as well. For reasons of their own, India, Indonesia and Japan have all contributed to the paralysis.

"The largest RCEP members do not have FTAs with each other, whether it is India-China, Japan-China or Japan-South Korea," says Ms Sanchita Basu Das, who leads economics research at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. "Their bilateral issues weigh heavily on RCEP negotiations."

Still, it will be impossible now for RCEP discussions not to take into account the CPTPP when setting their own, even if lower, benchmarks. Indeed, the addition, this year of government procurement and e-commerce - both part of CPTPP - is indication of how thinking has already been altered.

Heroic as his efforts to revive TPP have been, Mr Abe's crowning glory - both as a champion of globalisation and a leader of Asia - will be if he not only gives his unequivocal backing to RCEP, but also uses his considerable heft to prod the recalcitrants to produce a quality deal.

Already, by being the prime mover behind the strategic dialogue called Quad - comprising Japan, the US, Australia and India - he has shown a tendency to bypass South-east Asia. To do so on the trade front as well (never mind that four Asean states are part of CPTPP) would make him less of a pan-Asian leader than he aspires to be.