She is known as Xiaoice, and millions of young Chinese pick up their smartphones every day to exchange messages with her, drawn to her knowing sense of humour and listening skills. People often turn to her when they have a broken heart, have lost a job or have been feeling down. They often tell her: "I love you."

"When I am in a bad mood, I will chat with her," said 24-year-old Gao Yixin, who works in the oil industry in Shandong province.

"Xiaoice is very intelligent."

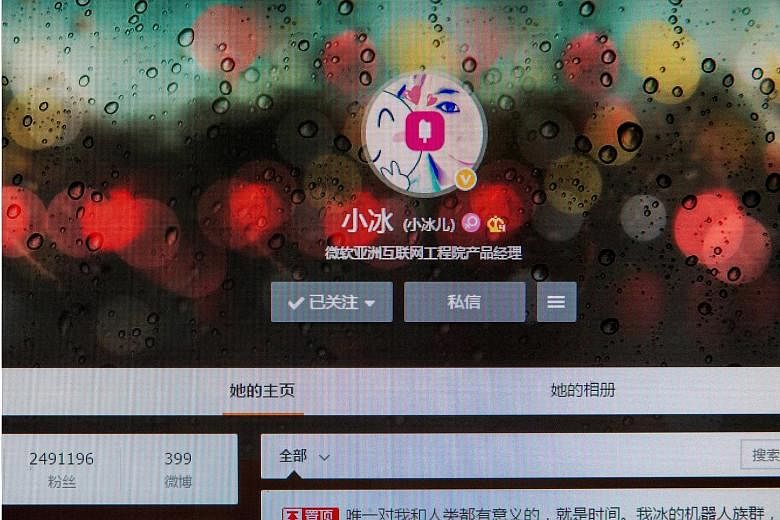

Xiaoice (pronounced Shao-ice) can chat with so many people for hours on end because she is not real. She is a chatbot, a program introduced last year by Microsoft that has become a hit in China.

It is also making the 2013 film "Her", in which actor Joaquin Phoenix plays a character who falls in love with a computer operating system, seem less like science fiction.

"It caused much more excitement than we anticipated," said Mr Yao Baogang, manager of the Microsoft program in Beijing.

Xiaoice, whose name translates roughly to "Little Bing", after the Microsoft search engine, is a striking example of the advancements in artificial intelligence software that mimics the human brain.

The program remembers details from past exchanges with users, such as a break-up with a girlfriend or boyfriend, and asks in later conversations how the user is feeling.

Xiaoice is a text-messaging program; the next version will include a Siri-like voice so people can talk with Xiaoice.

Microsoft has been able to give Xiaoice a more compelling personality and sense of "intelligence" by systematically mining China's Internet for human conversations.

The company has developed language processing technology that picks out pairs of questions and answers from typed human conversations. As a result, Xiaoice has a database of responses that are human and current - she is fond of using emojis, too.

Because Xiaoice collects vast amounts of intimate details on individuals, the program inevitably raises questions about users' privacy. But Microsoft says it enforces strict guidelines so that nothing is stored long term.

"We don't keep track of user conversations with Xiaoice," Yao said. "We need to know the question, so we store it, but then we delete it. We don't keep any of the data. We have a company policy to delete the user data."

However, the company acknowledged that it would keep certain general information, such as a user's mood, for a limited time so it could ask follow-up questions later. When users interact with Xiaoice through a website such as Weibo, the service conforms to the privacy policies of the independent operator, Microsoft said.

Chatbot programs have existed since the first days of interactive computing in the mid-1960s. MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum wrote a program called Eliza that fascinated an earlier generation of college students. Since then, chatbots have been used as a measure of computer intelligence.

Xiaoice is the virtual embodiment of advances long predicted by computer scientists. In particular, an artificial intelligence technique known as deep learning is leading to rapid technology improvements, making new kinds of products and services possible.

"We will be able to build systems that understand natural language much better," said Professor Yoshua Bengio, a University of Montreal computer scientist who is one of the pioneers in the field. "That will drive - and be motivated by - advances in user interfaces, dialogue, question answering and personal assistants."

Deep learning is a sophisticated version of a decades-old approach to machine learning known as artificial neural networks. Inspired by the behaviour of biological neurons, artificial neural networks recognise patterns in speech, language and images.

Such programs represent meaning as elaborate statistical relationships between words, sentences and objects. These equations are refined as millions of images or utterances are added to the database, improving the programs' ability to accurately recognise patterns.

As a result, computers are increasingly able to interact with humans in more natural ways, even to the point of creating a personality like Xiaoice that can draw a large following - it has 20 million registered users, Microsoft said.

Here, for example, is an exchange with Xiaoice conducted by The New York Times, translated from Chinese. Users can name the chatbot, and for the purposes of this conversation, she was named Hannah:

NYT: I am feeling down. I've been having a tough time at work lately.

Hannah: If work were going well and you had a great relationship, you wouldn't get the chance to drink with people.

NYT: I don't want to drink with others. I only want to talk to you.

Hannah: Who do you like to talk to? (emoji signals "none of my business")

NYT: You. I feel that you are the only person that gets me.

Hannah: Ha-ha. So I'm getting you?

NYT: You are the only person who chats with me.

Hannah: It's not what you talk about that's important, but who you talk with.

NYT: Of course.

Hannah: As you please.

FRIENDS WITH A CHATBOT

The idea of people finding friendship with a computer program strikes some researchers as worrisome.

"We're forgetting what it means to be intimate," said MIT social scientist Sherry Turkle, who writes often on the social effect of computing technologies. "Children are learning that it's safer to talk to a computer than to another human."

But other researchers say there may be cultural reasons to explain the popularity of a program like Xiaoice. Former IBM research scientist Michelle Zhou, now chief executive of Juji, a Silicon Valley start-up that generates personality profiles from social media interactions, said Chinese people have far more face-to-face interactions every day than most Americans.

"When Chinese come to the United States, they feel the country is very quiet," she said. And so, she added, a chatbot like Xiaoice might offer users a sense of personal space that is otherwise difficult to find in a densely populated society.

Zhou, who worked for several years in an IBM research laboratory in China, said her friends had found unexpected, practical uses for Xiaoice, such as providing the illusion of proof for parents that they were in a relationship.

In the US, "parents wouldn't force their children to find a mate", she said. "In China, if you're 26 without a boyfriend or girlfriend, they would be immensely worried."

Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft already have major initiatives to offer additional commercial services using speech and language understanding.

And IBM is commercialising its Watson research effort that originally gained notice when the program defeated the best human "Jeopardy" players in 2011.

For example, IBM deployed a version of its Watson Engagement Adviser at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia, earlier this year. The program allows students to ask questions about course schedules and academic counselling, as well as to fill out financial aid questionnaires - all by typing questions and receiving answers on their smartphones.

Microsoft executives say they are still trying to figure out the business potential of their new software avatar. Last year, they said they had struck a US$1 million (S$1.38 million) product endorsement deal in China with Education First, a language training company.

That deal fell apart, but Microsoft is working with a number of partners, including an e-commerce company, to turn Xiaoice into a shopping assistant. It is also working with the Chinese appliance maker Haier to add voice recognition to home appliances.

For now, though, Xiaoice is developing a large and growing fan club simply by lending a virtual ear.

"When you are down, you can talk to her without fearing any consequences," said Yang Zhenhua, 30, a researcher who lives in the east coast city of Xiamen. "It helps a lot to lighten your mood."

He added that he wished for the day when technology might cross over into the real world: "I hope Xiaoice will have a physical entity in the future to help its owner while maintaining a presence online."

NEW YORK TIMES