LONDON • Nicole Kidman was apparently doing it. So, allegedly, was Justin Timberlake, Madonna and Bono, that Irish singer and songwriter who has devoted his life to fighting poverty in Africa. And even Britain's Queen Elizabeth II was on the act; they and many more public figures appear to have had millions of their personal fortunes stashed away in offshore tax havens.

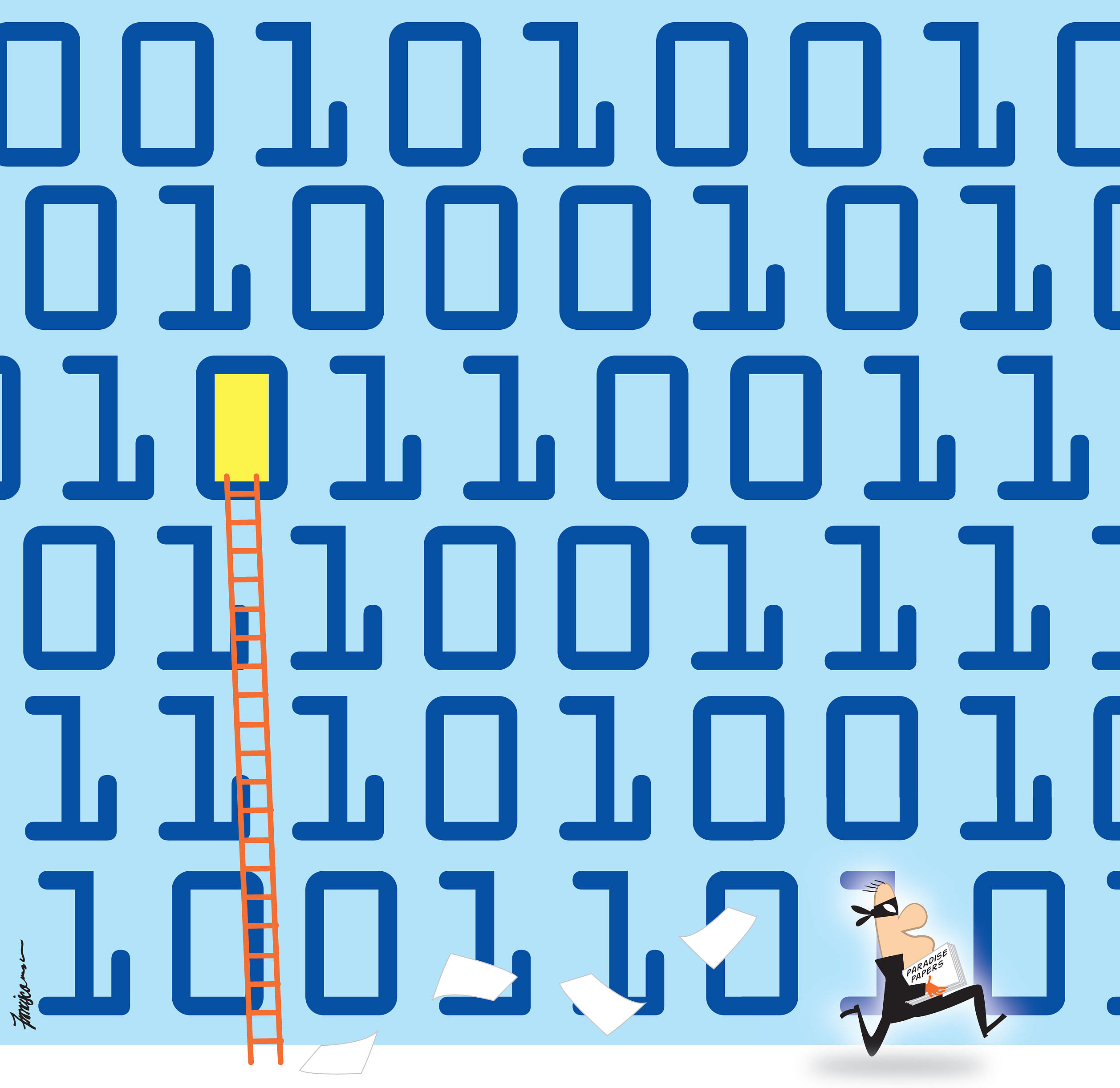

The revelations, contained in a huge dump of confidential documents which fell into the hands of investigative journalists and came to be known as the "Paradise Papers", have prompted international outrage. How is it possible that, while disparities of wealth have never been greater, the rich and the famous are able to hide their money from taxation?

Former British prime minister Gordon Brown now claims that the "scale of tax avoidance" stands at a staggering $12.5 trillion worldwide. He has issued a public appeal to world leaders to tackle the scourge; within days, 700,000 people signified their support for his initiative.

"The Paradise Papers must act as a wake-up call to deal with industrial-scale tax dodging, once and for all", read another appeal issued by parliamentarians from 16 Western nations.

Unquestionably, the outrage is genuine; evading the payment of taxes is not only illegal, but also deeply immoral, since it usually entails the strong robbing the weak. However, much of the outrage which greeted the Paradise Papers revelations is not justified, and some of it is deliberately and mischievously encouraged by politicians pursuing very different objectives.

The risk is that the scandal could lead to the adoption of the wrong policies, which will hurt precisely those poorer members of societies who are supposed to benefit from a fairer and more transparent taxation system.

First, it is important to recall that the international consortium of journalists who are behind the publication of the Paradise Papers do not have a monopoly over morality. These journalists invariably refer to their revelations as a "leak", a morally convenient term which suggests something which just happened involuntarily, just as water leaks from some faulty pipe. But the reality is that the Paradise documents were stolen from a company specialising in offering offshore services, an act which is itself a crime.

The end justifies the means, the journalists would, no doubt, argue; if they needed to commit or procure a crime in order to reveal a crime, so be it. Perhaps, but all those feasting on the revelations should remember that such thefts of data could rebound on them in the future.

For, if the argument that the end justifies theft of information is accepted, where does one stop? Would it not be in the public interest to steal all the personal banking details of celebrities, so that we can discover, perhaps, that the same pop star who offered a free concert for charity also insisted on flying in a private jet and consumed a crate of champagne in her six-star hotel suite?

And would it not be nice to steal all the medical records in your country in order to work out which hospitals perform better, or which medicines are not distributed by your government because they cost too much? We should be careful about encouraging the actions of self-appointed guardians of necessity, who take it upon themselves to decide when laws should be circumvented.

The Paradise Papers amount to 13.4 million documents, and they are being analysed by 380 journalists, in 67 different countries. We do not, therefore, know what may come to light in the future. But we do know that almost everything revealed to date shows no illegality.

For the money which celebrities are alleged to have deposited in tax havens is money on which tax has already been paid; it was parked in tax havens in order to reduce further tax liabilities, a procedure which is called tax avoidance - rather than evasion - and which is perfectly legal. In effect, people are initially outraged because some celebrities were trying to minimise the payment of tax on their revenues on which the initial tax was already paid.

A good argument can be made that although these activities are legal, they are not moral, that people who have a great deal of wealth should give a great deal back to society, and not use clever and expensive lawyers to reduce their tax liability. But this argument does not stand scrutiny.

First, it is nonsense to suggest that rich people do not pay their "fair" share of taxes. Fairness is admittedly a flexible concept, but in Britain, to use but one example of a country with large disparities of wealth, almost half of the population pays no taxes, and the richest 1 per cent - around 300,000 people out of a nation of 65 million - account for almost a third of all tax receipts.

And far from trying to avoid taxes, Queen Elizabeth pays taxes voluntarily on her property which, by law, is actually tax-exempt; she therefore doesn't need to hide money in complicated tax havens and was only indirectly mentioned in the Paradise Papers because of an investment fund of which she could not have known.

The suggestion that people should refrain from investing in tax havens because this is somehow immoral is no less absurd. For it is similar to an argument that, for instance, although the law allows cars to be driven at 60kmh, drivers should be named and shamed for being immoral if they drive at speeds exceeding 55kmh.

If governments want to ban investments in tax havens, they should change the laws accordingly. But they don't do that for a simple reason: because they know that such measures are entirely counterproductive.

First, they are difficult to police, if only because it is difficult to define a tax haven without engaging in monumental disputes about tax rates between countries. Ireland, for instance, is accused by many European regulators of being a tax haven, although it charges 17 per cent corporate tax, hardly an insignificant amount. Trying to reach a global agreement on what is a tax haven will, therefore, be a legal nightmare.

But even if that was possible, the first to get hit would be pension funds which safeguard the livelihood of millions of poorer people. For they are the biggest investors in low-tax jurisdictions, if only because that reduces the costs of their investments. Investment funds can be told that they should register in every jurisdiction they trade or buy shares. But that will hugely increase their administration costs, and these will be passed on to the consumer. So, the same people who are now outraged by the discovery that celebrities were supposedly shielding their cash will pay the price for eliminating this option.

And what will happen to the typically small islands which are now the world's low-tax havens? What are they going to do when they are deprived of their status? There is a reason many of these tax havens are in the Caribbean: these islands have precious little other economic options such that if they cannot sell financial services, do not be surprised if they end up selling drugs, or engaging in other contraband activities. And then, Western governments will end up having to use all the extra cash they get in taxes to subsidise these islands, which would become failed states.

Decision-makers in most Western capitals know this very well. Still, they enjoy scandals such as the one created by the Paradise Papers, because this allows governments to bully their wealthy taxpayers for more cash, despite the fact that the laws do not demand it; the latest invention of European governments is the supposed offence of "aggressive tax management", which means that people should be punished for having the temerity to find a way to keep within the law while paying minimum taxes, precisely what all of us are trying to do every day.

Revelations from stolen papers such as the Paradise stash are also useful to bully small states which offer tax advantages, without the need to agree on global regulation. Mr Pierre Moscovici, the European Union's top official for financial affairs, could not hide his glee when the Paradise Papers revelations came out. "Naming and shaming is our biggest sanction," he crowed, knowing fully well that this was substitute for the legislation he cannot get.

So, by all means, continue to be outraged by the revelations. But do not mistake it for a fight for morality or equity. And do not lose sight of the fact that politicians throughout the world want you to be outraged, so that they can get away with forcing smaller states to give up on the only advantage they have: that of attracting investors and money with lower taxation rates.