Imagine buying things just by blinking. Imagine doctors making an artificial heart for you within 20 hours. Imagine a world where garbage costs more than computer chips.

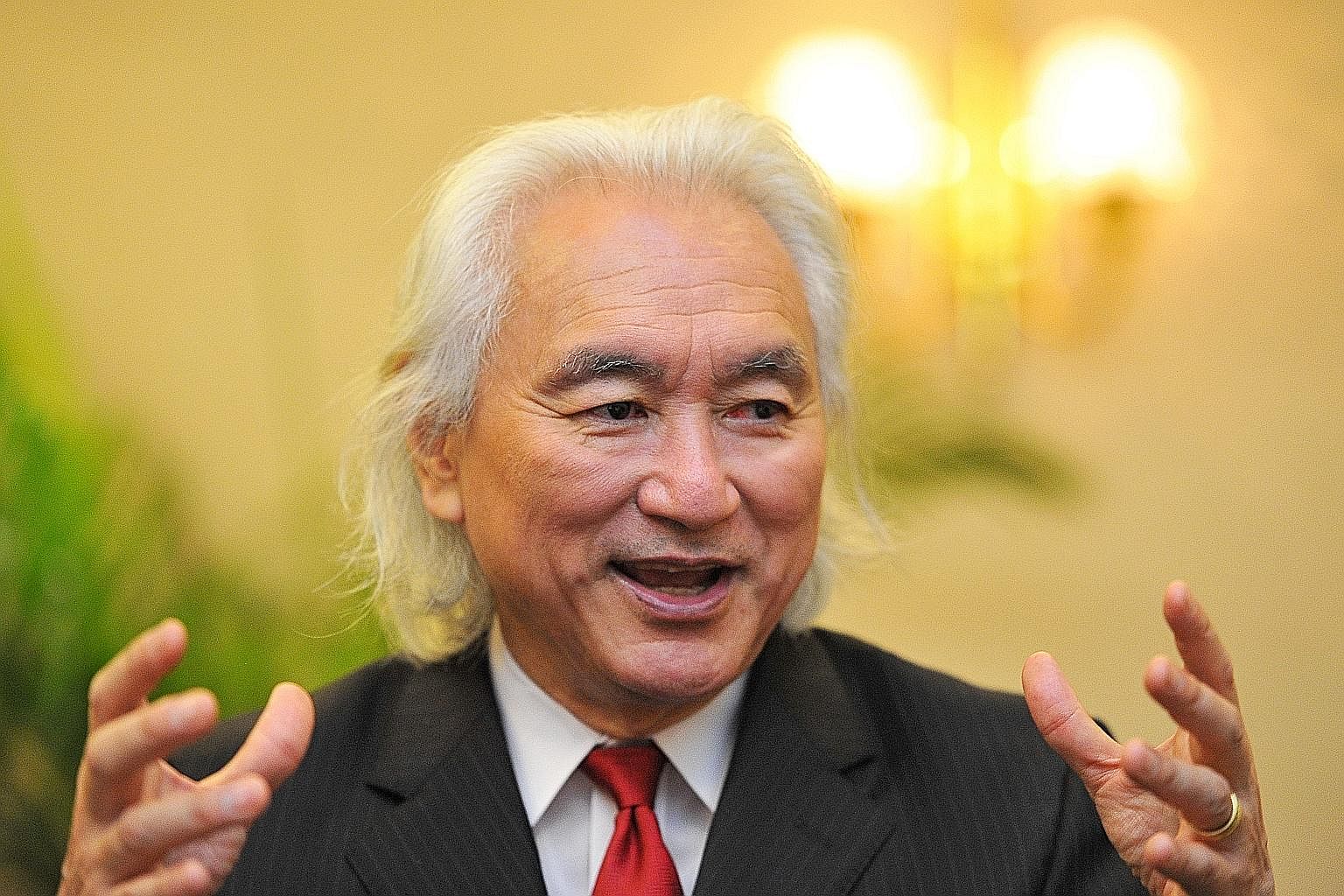

The thing is, says renowned American physicist and futurist Michio Kaku, all of this will be real within the next 50 years.

Forget Google Glass, for one thing, he says. In the future, online shopping will be just an inserted Internet-enabled contact lens away.

Gone too will be the days when those on famously long lists for heart transplants die waiting, as "human body shops" mushroom to 3D-print replacement organs for them.

Computer chips will be so pervasive - woven into your clothes to monitor your pulse and flab, embedded in your toilet bowl to detect cancer cells early, lining walls that can change colour on command - that these will be as cheap as, well, chips.

In an interview last Friday on the sidelines of the Singapore Institute of Management's yearly thinkers' pow-wow the Singapore Management Festival, Professor Kaku, 68, calls that very digitalisation of life "perfect capitalism" - that is, all enterprise will be owned privately and so the prices of all things will be set solely by the forces of supply and demand.

Ever witty, packed with punchlines and speaking in a rapid-fire throttle, he hastens to add: "But capitalism itself is imperfect, so whenever you buy something, you don't know how much people are cheating you with the prices they charge!"

Imperfection aside, he says the current march towards perfect capitalism means that commodity capitalism, based on the buying and selling of agricultural produce, will tank and take repetitive jobs down with it. Already, he points out, commodity prices on average have been dropping steadily, and most children of farmers have abandoned their parents' fields to try their luck in the city.

The wealth-generating engine, then, will be brainpower, which he calls intellectual capitalism. The rub , he points out, is that while there are ways to reduce costs in commodity capitalism, "the brain cannot be mass-produced".

The upshot of IT-driven capitalism, he adds, is a cheaper, more convenient lifestyle. The snag? Many people may no longer have jobs to afford even that way of life, as robots replace them.

All is not lost, though, he insists.

Computers are best only for "dull, dangerous and dirty" jobs that are repetitive, such as punching in data, assembling cars and any activity involving middlemen who do not contribute insights, analyses or gossip.

To be employable, he stresses, you now have to excel in two areas: common sense and pattern recognition.

Professionals such as doctors, lawyers and engineers who make value judgments will continue to thrive, as will gardeners, policemen, construction workers and garbage collectors.

"Every crime, and every construction site, is different," he says, underscoring the pattern recognition needed in such jobs, that reductionist computers simply cannot do.

This is because where humans see, say, a round side table with a circular base, computers can see only two circles and a line.

"The laws of reality are beyond computers," he asserts. "Computers cannot make value judgments. Children know that a stick can push but not pull, but computers can't know that."

What this brave new world bodes for Singapore, he stresses, is a cultural change, one that focuses on innovation.

"In the past 50 years," he notes, "Singapore has become a main player on the world's stage.

It's on everyone's shortlist of places to be."

The Republic, however, "needs a new way of thinking" if it is to be a leader in the next half-century.

"The culture has to change," he stresses. "People who kept asking questions were seen as troublesome and so like nails to be hammered down because they made their teachers look stupid. The system was trusted to squash people. Do you think Bill Gates and Steve Jobs could have been what they were if they had been born in Singapore?"

To be sure, it is not a uniquely Singaporean problem.

He muses: "We train people to live in the 1950s. Even physicists like me teach science in abstract, using rubber balls, light bulbs and pulleys."

To change for the future, then, he says Singapore would need to:

• Excite the young about science and technology, which he says are what really creates wealth, "so that we do not lose them to investment banking, which just massages other people's wealth";

• Lower taxes for start-ups and fledgling private enterprises; and

• Become so business-friendly that you could set up a company via your smartphone.

The big picture, he adds, is that the Internet is changing the very idea of what a nation should be.

"That is a good thing because the spreading of technology and information is the spreading of democracy," he says. "And democracies do not go to war with other democracies. List all the wars you know, and you will see that."

What, then, of the ancient Greeks, who introduced the idea of democracy, and who waged quite a few civil wars?

Not one to cede his ground easily, Prof Kaku retorts that that happened when Greece was a nascent democracy.

Born in California to Japanese immigrant parents who were interned during World War II, he had read the autobiography of Albert Einstein by the age of eight and resolved to be a physicist like him.

The alumnus of Harvard University and the University of California at Berkeley went on to co-create the groundbreaking string field theory, which suggests that the universe is akin to an ever-expanding soap bubble, at Princeton University, incidentally Einstein's alma mater.

Married with two daughters, Prof Kaku now teaches at New York's City University and also makes science popular through his many radio and TV shows.

Three of his 14 books are New York Times best-sellers, including 2014's The Future Of The Mind.

His biggest fear about the future is terrorism, which he says is a "reaction" to civilisation as we know it evolving into one in which humanity controls the planetary system.

"The great fear is that some do not want to be part of this great transition. In their gut, they do not like science and multi-culturalism. They are against democracy and they want to live thousands of years in the past."

In any case, he muses: "The future is a freight train.

"Some say, 'I'm too old, I can't get on it.' The young say, 'Get me in the driver's seat.'

"So are you going to jump on the train or be run down by it? It's your choice."