KUALA LUMPUR • At first glance, the glitzy neighbourhood of Bangsar, which is filled with chic restaurants, may not be the ideal place to undertake an oral history project.

But to Mr Kenneth Wong, who moved here two years ago, it's actually a great place to unearth stories.

Beyond the glitz, he said, Bangsar is still home to old-timers who have seen the area evolve from a railway neighbourhood to one that is the darling of hipsters.

Look hard enough, and Bangsar still has old-school racquet shops and kopitiams (coffee shops).

Over the last two months, Mr Wong has gathered some of these stories, and strung them together to form neighbourhood community walks, under his organisation People, Ideas, Culture.

"Development here has become so rampant that I'd like to create awareness about these old stories before they are lost,"?said Mr Wong, who previously worked in think-tanks on urban rejuvenation.

He may have chosen an unconventional neighbourhood for his project but he's not the only one actively recording the stories of yore in Malaysia.

Penang and Ipoh, in particular, have seen many oral-history recording projects, likely because these two old cities are undergoing rapid transformation due to tourism and other development. There is fear that their character may be lost to gentrification.

Some major projects include the Perak Oral History project, an ongoing effort that began several years ago with a focus on the Japanese Occupation in Perak.

George Town in Penang is, by far, the most established in these projects. It is bursting with such initiatives, not just for the historical archives but also as educational tools.

Currently, there is a three-year project to document 100 people who have lived at least 40 years in George Town, and worked in specific trades.

Ms Kuah Li Feng, a private consultant who is managing the project, said the plan is to store these recordings in public archives. In Singapore, the National Archives has an online portal that acts as a repository for maps, photos, articles, and recordings and other materials. The data is available to researchers.

RESURGING INTEREST

Malaysia is seeing a resurgence of interest in history, with many history-related events, new social groups and books now enlivening its social scene. This is, perhaps, also part of the process of finding ways to knit together as Malaysians at a time of political, social and religious fractiousness.

Ms Janet Pillai, a former associate professor at Universiti Sains Malaysia who is now an independent researcher in arts and culture, said it's also spurred by the easy availability of tools such as video-recording and Internet-hosting services.

It has become easy to record old stories even as more and more people move to the cities, where the oral transmission of knowledge and stories is often lost, said Ms Pillai, who runs Arts-ED, a non-profit organisation which provides culture education for young people.

Recorded interviews put on public archives are substitutes for oral transmission.

Ms Kuah adds that the systematic archival of stories can be an invaluable resource for researchers.

"It's people's histories which contribute to the social history of a place," she said. "If these are studied in depth and there are enough stories, we can unearth the local wisdom and ways of doing things, their use of space and social habits."

Far from being a "dead" record of "dead" events, oral history is a significant part of the process of "cultural mapping", a tool for effective town planning and development, said Ms Pillai.

"Cultural mapping" is a process to map out how people use their spaces, their invisible cultural networks and social interactions, and how they responded to change. "How do you preserve the cultural characteristics of places, the spirt of the place, if you don't know how the people live, and build to combine the space with inherited culture?" Ms Pillai said.

"People's attitudes and perceptions, skills, knowledge and values can only be known by recording their oral history."

The information can be used to identify social or other issues, and create better public spaces and developments.

Oral-history projects can also shed light on the hidden sides of the country, bring people together and offer dignity to the voiceless.

Ms Pillai recalled a project that she led in George Town several years ago to record the stories of the Japanese Occupation. Children were assigned to interview people who had lived through that time, and then to retell the stories to the interviewees in street theatre.

At the re-enactment, she recalled, the interviewees sat spellbound by the stories of each other as they had previously known of the Japanese Occupation only from their own perspective. It turned out that there were many diverse experiences with the Japanese, from bad to good.

"It must be remembered that all oral histories are a singular point of view. It's an experiential view, and different people have a different relationship to, or memories of, the same event like the Japanese Occupation," she said.

Seeing different perspectives can draw people closer together.

UNEXPECTED RESULTS

The projects bring unexpected results.

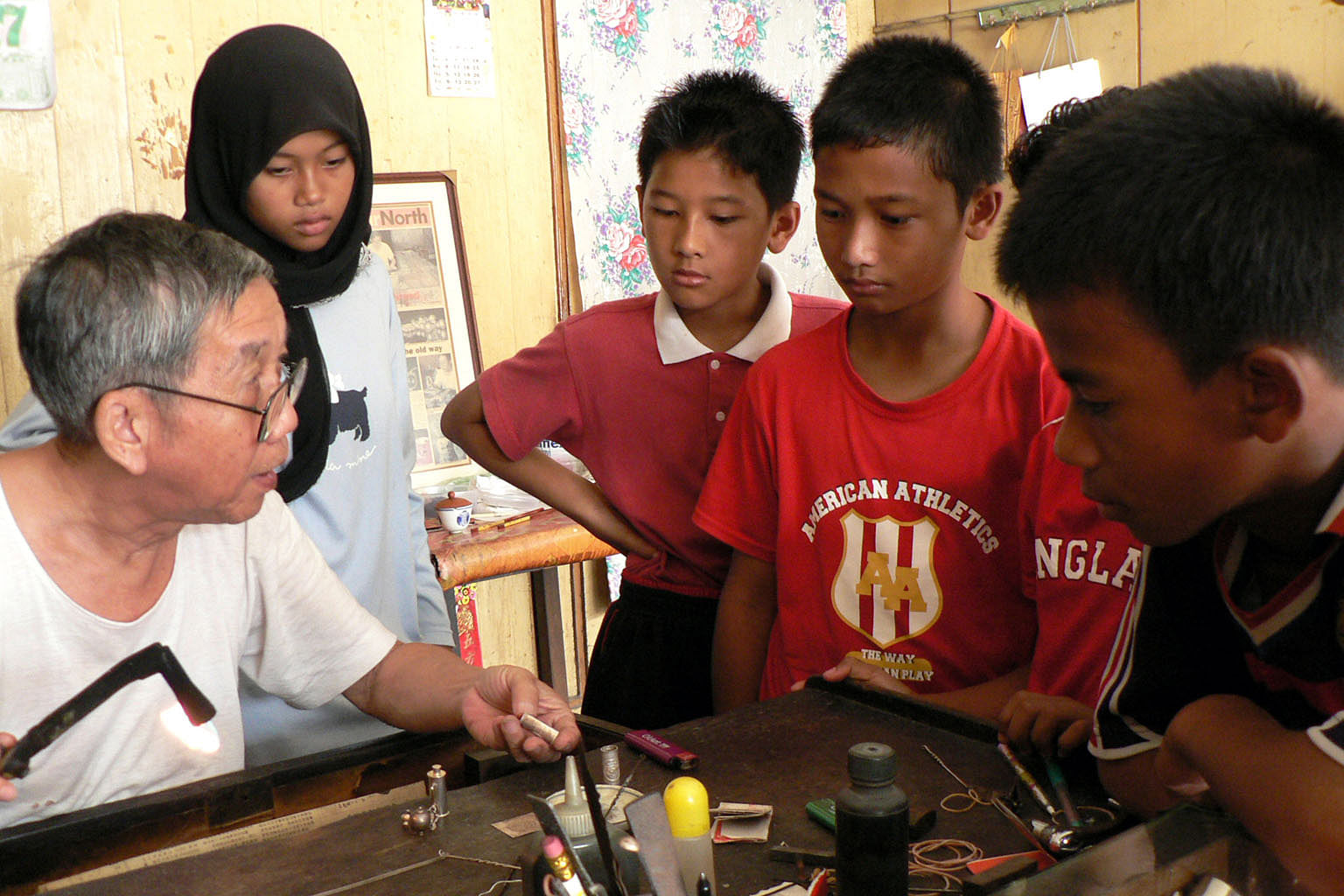

With Arts-ED, Ms Pillai ran another project with children to produce leaflets about the traders of George Town. The leaflets were an immediate hit with tourists as they allowed visitors to interact with craftsmen who often do not speak English, instead of merely photographing them like exhibits.

"It brought dignity to the trader, and they felt valued when people came to learn about them," she said.

But the leaflets also turned these traders into tourist magnets, with inadvertent side effects. Some chose to cash in on their fame by using their art to make trinkets. Others had their crafts snapped up by middlemen to be resold at a heftier price, along with the leaflet on their story, of course.

Then, there was the even more dramatic incident of the Balik Pulau booklet, produced by Arts-ED as part of an oral-history project to document the people of this rural side of Penang.

Aimed at promoting inter-generational communication, it was children who interviewed the senior citizens to write down their stories.

The booklet became a political hot potato two years later in 2009, when political rivals of Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng seized upon it to accuse him of denying that the Malays were the earliest settlers in the area, based on the interviews in the booklet.

Lost in the war of words was the fact that the booklet had nothing to do with politics or the state government, or that it was a children's oral-history project, not an authoritative history of Balik Pulau.

Ms Pillai noted: "What we did not predict was that once oral history was put into the public realm, in a media that moves at rocket speed, the reaction is also 10 times faster."

New technologies have also spurred more hit-and-run type of projects, where the stories are told by the interviewer with a camera, talking over the interviewee in the background. There isn't the leisurely process of building relationships or of listening for hours to his stories.

This truncated process often hardens their oral history into an exotic commodity, with the interviewee becoming totally disempowered.

"They have the will to document, they have the tools, but most have no experience with the ethics of it," Ms Pillai said. "But there are also good things about new technology - the new ability of the media to show cultural variety and highlight the marginal has become tremendous.

"We need to always ask ourselves: What is the impact, and are we creating respect or consumerism?"

The best practices, said Ms Pillai and Ms Kuah, are to let the interviewee speak, and to go back to them with the stories for their approval. After all, it is their story.

The stories should also be documented with proper referencing and sources, and be presented clearly as one point of view. Ms Pillai noted that oral histories are subjective views, not the objective one of a researcher.

These challenges notwith- standing, there is still a strong interest in the recording of oral history.

Ms Kuah, who runs Studio Good Think, a private consultancy which does cultural research, has received requests from temples, developers and even politicians who want to know the stories of their location for different reasons, often to preserve the spirit of the place or for community-building programmes.

"Everyone wants to know their story," she said.