The Council of the Royal Court in Selangor is more than a feudalistic, ceremonial body. Headed by the Sultan of Selangor, it is, in fact, a relevant and powerful panel which advises him on virtually all issues.

The role and function of the 19-member body is to aid and advise Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah in exercising his role. The panel comprises his son, the royal members, the elders and the Mentri Besar.

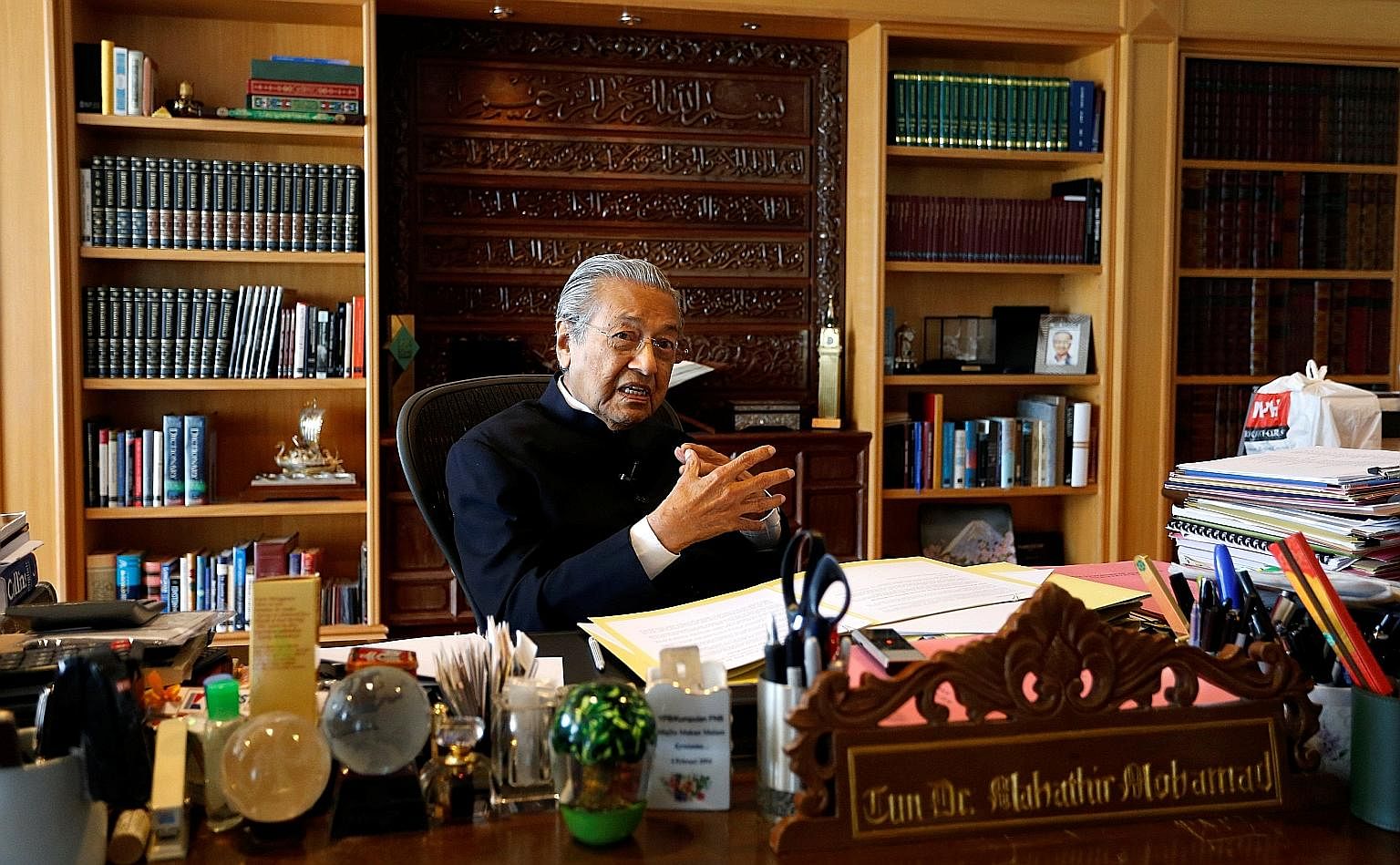

One of its members is Tan Sri Hashim Mohamed Ali - brother-in-law of Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad. The decision of the former premier to return two awards conferred by the Sultan last week has put Mr Hashim in an embarrassing spot. More humiliatingly, his sister, Tun Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali, also handed her awards back.

Dr Mahathir was the recipient of two medals of honour - one in 1978 from the then Selangor Sultan and the other from the current ruler in 2003.

Last Thursday, a representative showed up at the palace to return the awards on behalf of Dr Mahathir.

In the words of an eyewitness, it was "neatly packed" with an accompanying letter from a long-time private secretary who had served him since his days as prime minister.

The surprising spectacle, to put it bluntly, went down badly with most members of the royal court. Mr Hashim, in the eyes of some members, though blameless, was still apologetic.

Dr Mahathir's decision to return the awards came shortly after the ruler publicly expressed his unhappiness with Dr Mahathir over the latter's comments about the Bugis being "pirates". In an interview with The Star, the Sultan had also remarked that Dr Mahathir suffered from "inferiority complex" and that the former premier would only "burn down the whole country" with his deep hatred.

They were strong words indeed. But Dr Mahathir was expected to merely accept the remarks and criticism in good faith as advice from a highly respected ruler, and not end up sulking like he did.

The Sultan of Selangor is among the most senior rulers and he was clearly expressing the sentiments of his fellow sultans.

That itself is a vital point - that all nine rulers shared a stand against Dr Mahathir's actions and this wasn't the sentiment of merely one.

"This is the concern of all Malay rulers. The nine of us," said the Sultan of Selangor, referencing the misuse of race and religion ahead of the general election.

Dr Mahathir is not the first person to return honours awarded by Selangor. In 2011, former Selangor mentri besar, Dr Mohamed Khir Toyo, "temporarily" returned the state award, which carries the title "Datuk Seri", following his corruption charge. And when he was convicted in 2015, the title was altogether withdrawn by the Sultan.

Dr Mahathir's returning of the awards has won him the admiration of his supporters, including those who have backed him from day one, along with those who once detested him but now lauding his switch to the opposition bandwagon.

Then, there are those who feel that Dr Mahathir has, once again, crossed the line. The first time was when he sat next to Democratic Action Party (DAP) strongman Lim Kit Siang to begin the opposition pact. To the Malay voters in the rural heartland, it is something they find difficult to comprehend, especially after he spent his entire political career labelling the DAP racists and extremists.

The coming general election will be a test to see how much the majority of Malay voters are prepared to accept these dramatic and radical changes in the opposition's bid to bring down the Najib administration.

But his fellow opposition leaders are certainly unsure. Datuk Zaid Ibrahim, who is now in DAP, sent out a tweet urging the Sultan "to be careful with his words. No one is immune when the country burns".

Truth be told, it sounded like a warning to the Sultan. And certainly, to rebut a sultan in such an uncouth manner is not ingrained in Malay values, culture or psyche.

Mr Zaid found it surprising that no one, at least publicly, was ready to join or defend him, attested to by his tweet later that he felt alone in his crusade.

In fact, Selangor Mentri Besar Azmin Ali called for an explanation and demanded Mr Zaid to take responsibility for his statement, while DAP's top brass distanced themselves from his indiscretion.

No one being prepared to rebuke royalty speaks volumes of how sensitive it is perceived for a politician to take on or feud with them.

Dr Mahathir's brashness is well known, but the difference this time around is that he is no longer in Umno. He is now in the opposition.

He needs all the support he can get, and antagonising the rulers may not be the best way to help the opposition's cause. The Sultan of Johor has no love lost for Dr Mahathir, and he has openly made his stand known.

And don't forget that His Majesty carries plenty of respect and influence in Johor, a state eyed by the opposition, especially Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia, of which Dr Mahathir is chairman.

But that's not the end of his problems either. The 92-year-old politician has offered himself to be an "interim prime minister" but no one has responded because Parti Keadilan Rakyat, DAP and Amanah probably have Anwar Ibrahim in mind should the opposition Pakatan Harapan alliance win.

There is no doubt that Dr Mahathir's name continues to resonate with many sections of the Malay community, especially among the older ones. After all, for the longest time, he was the only prime minister they knew, with him at the helm for 22 years.

No one can erase what he has done to build Malaysia into a modern nation. He made Malaysians proud. But at the same time, his iron-fisted and authoritative rule continues to leave an unpleasant taste, a legacy of his time in charge.

It is also a fact that Dr Mahathir left an indelible impression on Malaysia history, so much so that foreigners are often heard uttering his name in awe when we say we are Malaysians. No one can dispute his great work.

But the challenge for him now, in his twilight years, is to see if Malaysians are prepared to let him lead the country again.

Even for those who would vote for the opposition, they find the thought illogical. Dr Mahathir's problem has always been his inability to let go.

He wanted Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi to implement things his way, and he expected the same of Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak.

Dr Mahathir has given the impression that only he has exacting standards, therefore, he has to be left to run the show, again.

None of his deputies when he was prime minister, like Tun Musa Hitam and Anwar, could work well with him. Only the late Tun Ghafar Baba did, but that's probably because he did not see the mild-mannered Mr Ghafar as a threat.

For practical reasons, the opposition, which is unable to galvanise the battle in the absence of Anwar, sees Dr Mahathir as a useful ally. But should Pakatan Harapan win, a fresh round of feuds will surely surface.

If there is an important lesson here for politicians, whether those in office, aspiring to be elected, or returning from retirement, it is this - leaders come and go, but rulers remain.

Dr Mahathir has learnt the consequence of putting them down previously.

The present rulers were merely raja muda and tengku mahkota (princes and crown princes) when Dr Mahathir, who was Prime Minister then, removed the legal immunity of the royalty in an amendment to the Federal Constitution in 1993. But now, they appear to be striking back.

Istana Bukit Kayangan, to where Dr Mahathir returned the medals, was once stripped of police sentries, guards and outriders, to humiliate Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah.

In a picture of failing fortunes with cut budgets, the roof of the palace, at one time, leaked too, the carpet getting soiled in the process.

And like most things in life, things have come full circle, and in the past 20 years, the roles seem to have changed.

THE STAR/ASIA NEWS NETWORK

• The writer is managing director/chief executive officer of The Star Media Group.