A recent slew of reports about the Covid-19 situation has painted a picture of confused Singaporeans unsure about how to respond to constantly changing rules, or worse, suggesting Singaporeans are taking fright and panicking over loosening restrictions.

For example, those on home quarantine or home recovery are upset when unable to get the Ministry of Health on its hotlines to clarify their next steps, or when they wait in vain for days for the promised swabber/quarantine order/discharge/transport to healthcare facility.

The Ministry of Health has apologised for delays and lapses in quarantine orders, and Health Minister Ong Ye Kung has admitted that protocols are "many and complex", "confusing and even frustrating", and promised a relook to streamline them.

Compared with six months ago, there is a general feeling that the Covid-19 situation is getting messy, the healthcare system is under strain, and the much-vaunted efficient Singapore state is struggling to cope.

The main reason is scale: On April 6, there were zero new locally transmitted cases of Covid-19. On Oct 6, six months later, there were 3,577 new cases, of which 2,932 were in the community. Daily new infections have generally crossed over 1,000 since Sept 19.

A season of see-saws

Many people have complained in recent weeks that Singapore's Covid-19 response flip-flops between locking down the economy and opening up. When Singapore moved into a heightened alert phase (dine-in for two only), then allowed more liberties (dine-in for up to five allowed), and then went back into a stabilisation phase (with dining in restricted once again to two), howls of anguish were heard across the island.

I was among those chastising the multi-ministry task force (MTF) for moving the nation back to tighter restrictions. "Screw your courage to the sticking place," I muttered mentally, recalling the Shakespeare quote, and grumbling about the events and dinner deliveries I would have to reschedule.

Surveys show that Singaporeans are split on the measures: 52 per cent felt that they were just right, 25 per cent that they were too strict, and 23 per cent that they were too lax.

Then I met some doctor friends for dinner and listened as they spoke about their relief - every tightening means fewer infections, and less demand for hospital care, which means a less taxing workload for those on the anti-Covid-19 front line who have been working flat out for at least 20 months.

When MTF co-chair and Finance Minister Lawrence Wong urged Singaporeans to reduce non-essential social activities for two weeks, just days after government leaders said Singapore would move to endemic Covid-19 mode, I rolled my eyes at the confused messaging. Consistency is the cardinal rule of crisis communication, don't they know that, I thought.

Like many Singaporeans, I was led down the path of speculation. Was there a split in views within the MTF, which has three co-chairs?

But speculation only feeds discontent. It also creates a climate where leaders are looked to for answers, scrutinised for decisions and blamed when things go wrong, and citizens passively follow. This is not the kind of society I want to live in.

I decided to pivot mentally to look at the issue from an active citizen's point of view. How does one cope in a crisis situation, when rules keep changing? How does one become a better, smarter, more responsible citizen?

A balcony view

To understand periods of complexity and change, it is useful to get on the balcony. This is an insight from Harvard professor Ronald Heifetz's adaptive leadership model. He encourages people to remove themselves from the dance floor to get onto the balcony to observe the surroundings - a metaphor to encourage people to detach themselves from an immersive environment, and get onto the balcony for a gallery view of things.

Getting onto the balcony, the rational citizen in me acknowledges that the frequent changes in rules are often necessary and sensible.

For example, the criteria for and scheduling of vaccine and booster shots may evolve as vaccine stocks come in or as new scientific evidence is verified.

Criteria for home recovery may be relaxed in mere days, as cases shoot up faster than anticipated; and more of those infected are then encouraged to recover at home to ease pressure on hospital beds.

Singaporeans like clarity and certainty. But pandemics are rapidly evolving, dynamic situations that require nimble decision-making. This agility comes at a price: It means rules change quickly, as the number of cases goes up, in response to ground feedback, or when the science advisory changes (for example, on the wearing of face masks last year).

Of course, some rules were ill considered to begin with. Take the Sept 7 rule requiring employers to mandate a snap, 14-day work from home (WFH) regimen if even one worker tests positive. I thought it was rather draconian when it was announced. It was amended from Sept 22 to kick in when three or more workers on the same premises test positive, and the WFH period was shortened to 10 days. This is more reasonable: Three cases might suggest workplace transmission, so moving to WFH can stop that cluster.

Changing an unreasonable rule, implemented too fast, is better than sticking to it; or worse, waiting days before having any rules.

The alternative to agile decision-making and constant iteration of rules is indecision and limbo, waiting till more is known before moving ahead. This is not optimal in a global pandemic. Such a business-as-usual mode would not have produced the vaccines that are now saving lives.

As many commentators have noted, the pandemic is testing the judgment and collective decision-making of the political and public sector leadership in Singapore.

But just as importantly, it is also proving to be a test of maturity for the people of Singapore.

The pandemic is challenging those of us in Singapore - citizens, permanent residents, guest workers - to respond in a manner that emphasises personal responsibility and collective benefit. To do so, however, we have to unlearn some old habits and adopt some new ways of thinking.

What helps in such an uncertain, ever-changing situation? For what it's worth, here are some rules to cope with uncertainty.

1. Realise that there is no either/or, only in-betweens

Many of us think in binary terms: lock down, or open up. But in this pandemic, there is no either/or solution. Each course of action has trade-offs.

The economy in Singapore currently is neither in a lockdown stage, nor in full reopening mode. Stores are open, but social distancing rules apply. Restaurants are operating, but dining in is only for groups of two. Offices are open, but work from home is the default.

It is likely to remain in such a state for months; and even when tilting towards reopening, periodic tightening will likely occur - in locations or demographics with more virus spread, for example.

Another either/or issue is over mass testing. Some experts have queried why so many people without symptoms are being tested for the disease if the plan is to live with endemic Covid-19. Implicit in the idea of endemic Covid-19 is letting the disease circulate freely - so why bother to test, and then trace and isolate contacts?

The short answer is that testing is not done randomly but selectively in high-risk sectors, such as on people in public-facing jobs (like in food and beverage) or those who come into contact with vulnerable people (healthcare, eldercare and education workers who work with patients, the elderly and children, who are not vaccinated).

Living with endemic Covid-19 does not mean letting the virus rip rampantly through the population. Testing higher-risk job categories is an intelligent, humane way to spot and ring-fence any infection and reduce the risk of it spreading across vulnerable groups.

From the start, Singapore has carefully chosen the harder, middle road: We did not choose an elimination (zero-Covid-19) strategy like New Zealand, Australia, China or Taiwan did, slamming their borders shut. Nor did we choose to let the virus spread in large numbers to develop herd immunity the way many European societies and the United States did.

Instead we went for suppression: maintain porous borders, keep the economy going, and yet work hard to stamp out the virus wherever it pops up, as quickly as possible.

Singapore will walk that same middle path towards reopening.

Living with Covid-19 does not mean living as though there is no Covid-19.

So expect more shifts in rules in the months ahead, and cycles of easing and tightening, in response to waves of infection. When this happens, understand the changes not as flip-flops, but as tweaks to tighten and loosen the circles to contain contagion to protect the vulnerable.

As we go through these cycles, the messaging will change. Singaporeans may sometimes be encouraged to accept big numbers of infection calmly, and at the same time be urged to reduce socialising to slow the spread. Rather than get confused over the mixed messaging, we can learn to be more discerning over what is being said.

For example, it is useful to understand the difference between the destination and the journey.

The destination, or exit plan out of Covid-19, is to reopen and live with endemic Covid-19 around us. The journey to get there, however, is varied: It can go slower or faster, can detour, and can even require a U-turn.

Some messages speak to the destination. Others apply only to a specific leg of a journey. Understanding the difference will help us cope with mixed messages at different stages of the journey and avoid feeling confused and anxious.

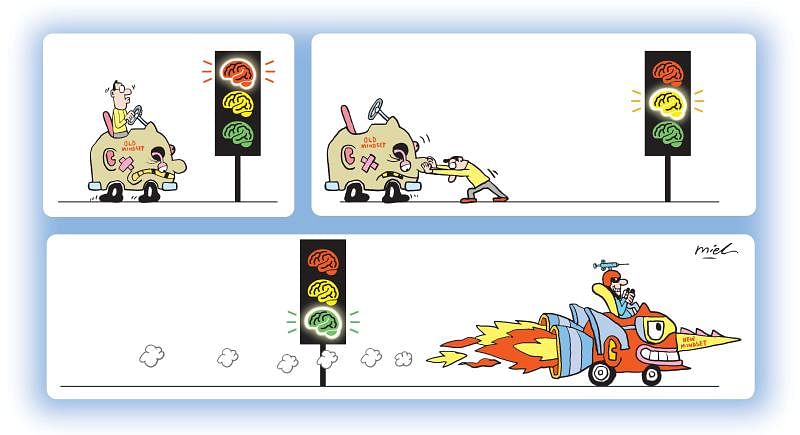

2. The 2020 playbook is no longer relevant. Update it.

Last year, the coronavirus was an unknown entity, and the disease it causes was dreaded and fearsome.

Today, Covid-19 remains a formidable disease, but most of us are vaccinated, which protects us from severe illness and death.

Last year, Singapore had few Covid-19 cases in the community; today, it has daily case numbers in the thousands. The 2021 Singapore resident cannot let his 2020 self take fright at the rise in numbers.

As Mr Wong has said, many people in Singapore will get Covid-19, and there is nothing to be fearful or embarrassed about in getting infected. Even though I had known mentally that the chance of getting infected is high - given the rising number of daily cases and my fondness for hawker centres and generally active social life - I heard Mr Wong's statement with a jolt in my heart. Me, getting Covid-19?

Many of us will need to confront the fear of Covid-19 that resides in us, after fighting and shunning it for 20 months. We have to consciously learn to face it and see that it is not as fearsome a disease as we had thought last year - because it isn't. Vaccination has reduced significantly the risk of severe illness and death from Covid-19.

One way to normalise Covid-19 is to publicise more reports of people who have the illness and recovered quickly. Then we can learn to treat it more like a bad flu or bout of chicken pox, and less like a cancer or terminal illness diagnosis.

This means not overreacting when the antigen rapid test is positive, not panicking, and not choking hotlines. Just Stay Calm and Stay Home to recover, and monitor temperature, pulse rate and oxygen saturation rate.

3. There is no timeline, because the virus calls the shots. Not humans.

Many of us like to know what's next, so we can mentally prepare for it. Alas, life - especially in a pandemic - offers no such timeline.

Even as many countries plan for an exit from Covid-19, the truth is that this coronavirus mutates fast, and no one can really tell when the Covid-19 pandemic can be declared over. The rapid development of vaccines has helped humans cope better with the virus - but emerging reports already suggest the leading vaccines are less effective against the Delta variant than earlier strains. Meanwhile, some other, more transmissible, more virulent, strain might be mutating, somewhere.

And even if Covid-19 is subdued and snuffed out, there is every risk that the next virus that invades human hosts may be deadlier.

In other words, we have to get used to not knowing when this pandemic will end, and when the next pandemic might erupt.

We have to be prepared for the long haul and learn to live in this stop-start world of uncertainty.

If other countries' experience is any guide, and as the MTF has tried to warn us, there may be multiple waves of infection ahead. This wave looks like it is not cresting just yet - and there may be higher waves down the road.

If we are to face this battle for the long haul, both the population and the leaders need to update their toolkit. Just as ministries need to relook their protocols, citizens need to update our mental model.

And one useful update is to learn to point the finger less at those battling the disease on the front line, and examine ourselves more, and learn how to reprogramme our own minds to understand and accept constant change and uncertainty with more equilibrium.