In 1961, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew remarked that "if no constitutional advance takes place, the PAP cannot hold the position in Singapore".

The comment - captured in a new book on significant moments in the development and evolution of the Singapore Constitution - seems prescient today.

Looking back on the past 50 years, the nation's constitutional development appears, intended or otherwise, to have been calibrated in accordance with context and circumstance.

Take the example of how various chief justices (CJ) have addressed issues that touched on the Constitution and interpreted laws that pitted individual rights against the powers of the State.

While CJ Yong Pung How favoured the State when interpreting laws in cases where individual rights came up against State power, his successor, then CJ Chan Sek Keong, sought to balance individual rights against public interest.

CJ Chan thus abandoned the "four walls " approach of the Yong Court and showed a willingness to consider legal arguments and cases from all jurisdictions.

A "four walls" policy is to interpret the Constitution within its own boundaries and not by drawing analogies from other countries.

These views, in a nutshell, on how different CJs handled constitutional issues start off a new book by two of Singapore's best-known constitutional law experts who scanned the cases, policies and institutions key to Singapore's constitutional development over the past 50 years.

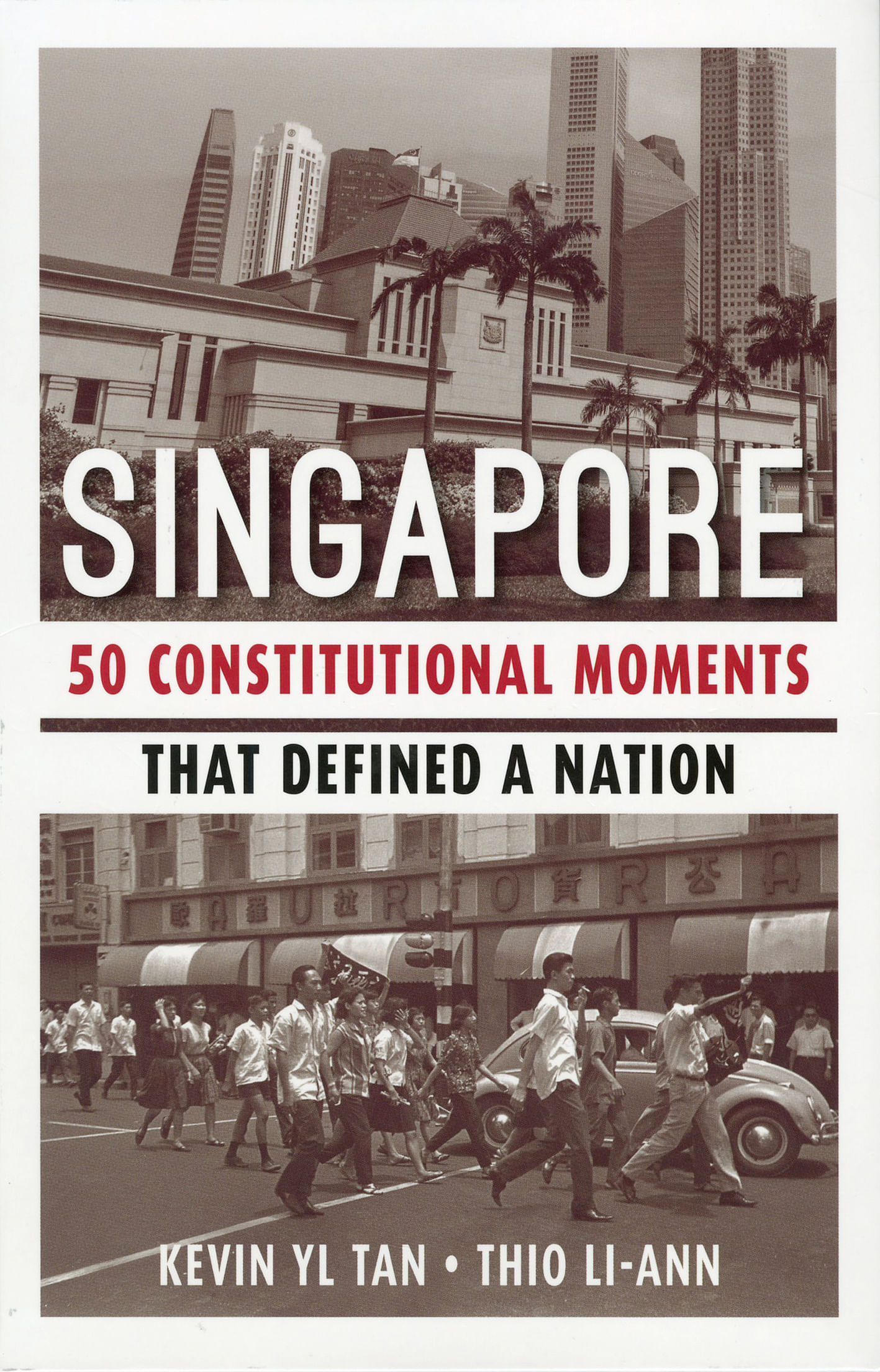

Titled Singapore: 50 Constitutional Moments That Defined A Nation, authors Kevin Tan and Thio Li-Ann said the 50 featured moments present "a good snapshot of the key issues in Singapore's constitutional law and point to a possible trajectory of where the discourse is headed".

Their collection of short essays which explain 50 constitutional moments from a personal perspective is crafted as a popular work, not an academic tome, and is aimed at a wider general readership. It befits inclusion in the Singapore conversation.

Dr Kevin Tan is an adjunct professor at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Nanyang Technological University, while Dr Thio Li-Ann is Provost Chair Professor of Law at NUS and, among others, a former Nominated MP.

Divided into three sections, the book first dwells on general developments, including the shaping of the Singapore Constitution, the short-lived graduate mothers' scheme in 1984 and the stand-off with the Law Society in 1986 over its assertiveness in commenting on proposed laws.

The second section discusses events linked to institutions such as the President's Office and the 2011 presidential election, while the third highlights cases and legislation that impact individual rights and public good.

These include the Little India Riot and Public Order (Additional Measures) Act, the death penalty debate and the right to vote as explored in Madam Vellama Marie Muthu's case in 2013 on calling for a by-election in Hougang after the seat fell vacant when the incumbent, Mr Yaw Shin Leong, was expelled from his party.

Court judgments mirror constitutional evolution and, to this end, the authors noted that many constitutional decisions under CJ Wee Chong Jin, Singapore's first chief justice, were "functional, workmanlike and read like trial court judges' judgments even when they emanated from the Court of Appeal".

The Wee Court, operating from 1965 to 1990, served when Singapore was pursuing development "most aggressively" and the "will of Parliament was given greatest latitude", they added.

CJ Wee was succeeded by CJ Yong, a former banker and lawyer, in 1990 - a surprise move as many expected Justice Lai Kew Chai, who had been on the Bench for almost a decade, to be named CJ, they wrote.

CJ Yong in his 16 years as Singapore's top judge succeeded in "transforming the judiciary into one of the most efficient and dynamic in the world". But decisions on constitutional matters by the Yong Court were pro-State in orientation, said the authors, illustrating with examples.

They cited the 1994 Jehovah's Witnesses case that came before CJ Yong as "the high watermark in the judicial defence of statist values".

"The Court evinced a distinct distrust of scholarly writing and in the precedents of foreign courts and more often than not took a literal anti-rights interpretation of the Constitution," said the authors.

Unlike the Yong Court, the Chan Court that followed took rights seriously and went to great pains to explain why constitutional rights are important. The quality of judgments on the whole improved dramatically during CJ Chan's term, the authors said, but they made it clear that it was by no means "activist, preferring a calibrated approach to review of executive action".

The authors observed that there was no detectable shift in approaches to constitutional interpretation between the Chan Court and the work of current CJ Sundaresh Menon, who took charge in 2012.

"Much that was initiated in Chan's era appears to continue in practice in the Menon Court," they noted.

The landmark moments in Singapore's constitutional development which the authors highlight include then Nominated MP Walter Woon's tabling in 1994 of the first private member's Bill: the Maintenance of Parents Bill.

It was a controversial piece of legislation as it was seen in several quarters as a pro-Confucian law to legislate filial piety.

The Bill sparked three days of impassioned debate in Parliament and attracted more than 1,000 representations from the public before it was passed into law two years later.

Separately, the authors probed Singapore's law in relation to political defamation - "a heavily litigated area which looms large in constitutional case law".

They suggested there are signs that defamation law in Singapore "is finding a new, positive equilibrium which gives due weight to free speech and reputational values".

Among other things, they noted that no political defamation suits were launched after the 2011 General Election, unlike preceding elections.

But whether it is the contentious 2007 debate in - as well as out of - Parliament over the desirability of removing Section 377A, the homosexuality clause in the Penal Code that forbids sex between males, or the alleged 1987 Marxist Conspiracy revisited, the authors conceded that the book's title, reflecting 50 moments of their choice, "is likely to invite controversy".

Perhaps.

But the authors are more likely to be lauded for celebrating the country's Golden Jubilee by contributing to the conversation on Singapore in the next 50 years, and as its laws and legal rulings are set to further evolve in tandem with society.

The book, published by Marshall Cavendish and priced at $39.90, is available at leading bookstores.