Last week, Pakistan called off its first National Security Adviser-level talks after New Delhi set clear red lines, including that the subject of Kashmir not be discussed, and that the visitor agrees to avoid meeting separatist leaders from the disputed region, even at a semi-public reception hosted by its envoy to India.

Instead, it wanted the talks to be focused on the issue of terror. Without Kashmir, the "core issue", as Pakistanis see it, there was no point in talking, and so Islamabad walked away.

The atmosphere in the run-up to the NSA talks, as described by the Indian foreign policy writer Suhasini Haidar, was like a family gathered around a dying relative, and debating who will turn off the life support. The cause, itself, seemed lost.

For whatever it was worth, and that does not seem like a lot, India could claim that it was the other side that had called off the talks. Sadly, just weeks earlier, the leaders of both countries, meeting in Ufa, Russia - a city built on the orders of Ivan the Terrible - had agreed to resume talking on "all outstanding issues" after a year of ups and downs since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took charge of India.

Once again, domestic pressures on both sides contributed to the failure to even meet, much less discuss, the many issues that have vexed ties between the two nations, separated at birth in 1947 when British colonialists departed from the Indian sub-continent.

Should the rest of Asia care? After all, the seven-decade-long animosity between the two South Asian nations has become, to borrow T. S. Eliot's words, a tedious argument filled with insidious intent. However, there are good reasons why it should matter.

India, with 1.2 billion people, and Pakistan, with 190 million people, aren't minnows in the world but the second- and sixth-largest nations by population.

They are armed with nuclear arsenals, which makes them mighty in a narrow sense.

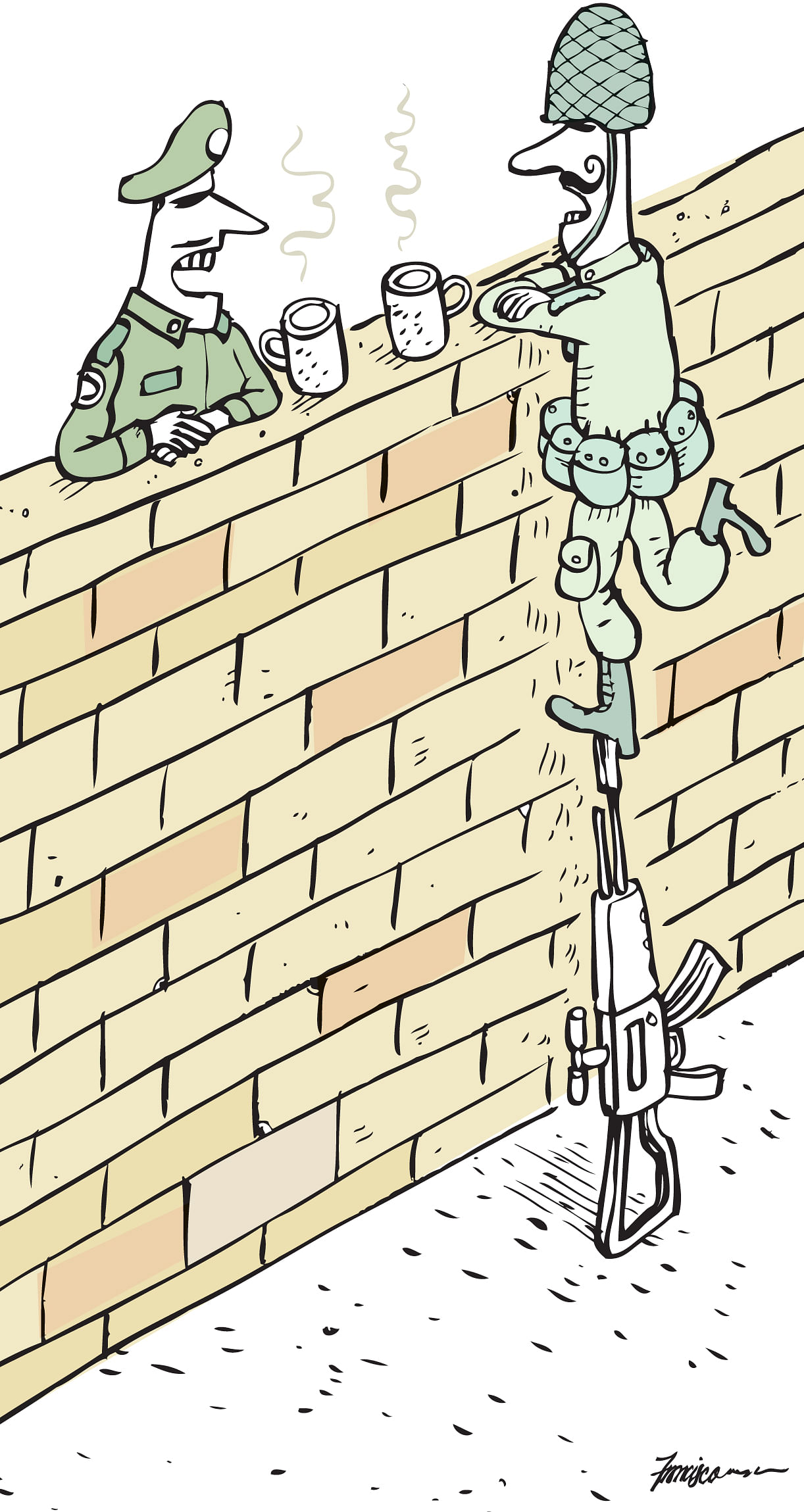

Yet, they are weak inside, facing multiple challenges, including poverty, internal strife, and no shortage of hot-blooded border guards who regularly trade gunfire across the frontier.

Because weakness is sometimes more lethal than strength, South Asia is only slightly less dangerous a spot than the Korean peninsula, when the Americans are exercising with South Korea close to the North's borders.

What's more, in the current climate, any outbreak of outright hostility between them, even if unlikely, also risks dragging in the United States and China, should the strategic connections taking shape between Washington and New Delhi run into the "all-weather" friendship China and Pakistan have enjoyed for decades. The last thing South-east Asia needs is an unattended fire in its backyard at a time when it is fixated on the front lawns, where the world's dominant power is confronting a rising China in the South China Sea.

Just as importantly, as Midnight's Furies, a recent book by the clear-eyed American journalist Nisid Hajari, suggests, the unresolved issue of Kashmir - and Pakistan's chosen weapons to fight that battle - has driven the smaller nation's destabilising behaviour from the start, in particular its use of insurgents as proxy tools of the state to even out the military imbalance. In 1948, the sense of vulnerability led Pakistan to fork out over 70 per cent of its first national budget to the military, at a time when the most pressing issue was resettling millions of refugees from India. From that point on, the military-led Establishment got to dominate Pakistan's national life.

This nexus between an insecure military and insurgent groups, Mr Hajari notes, created the Taleban in the 1990s, perhaps even protected Osama bin Laden, and "has metastasised into a cancer that threatens not just Pakistan but the wider world". Mr Hajari is not only referring to Pakistan, where the portrayal of insurgents as freedom fighters and defenders of Islam has complicated the way ordinary Pakistanis view militancy, but Islamist movements everywhere.

For the uninitiated, the blood feud between Pakistan and India is not easy to comprehend.

After all, until they were split into a Muslim-majority Pakistan and a Hindu-majority India in 1947, they had so much in common by way of history, life and cuisine. The British encouraged divisiveness between communities in order to prolong their rule. Once they decided to quit, they did so in haste and, certainly, were responsible for law and order until the grant of independence.

Mr Hajari says Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy, clearly miscalculated, too; not mining the depth of anger of the Sikhs - fully five million of six million Sikhs worldwide lived in Punjab - at the thought of their fertile province being truncated.

The British also were responsible for some creative cartography that helped India get a land route to Kashmir through Punjab, thus helping it to hold on to a province where the majority, certainly in 1947, may well have preferred to be neutral from both India and Pakistan.

As Mr Hajari told me recently, Lord Mountbatten believed the threat of massive force would be enough to dissuade Sikh leaders from fulfilling their vow to slaughter Muslims and drive them into Pakistan. He also did not ensure that the Punjab Boundary Force he had established was fully staffed and armed.

The result was that, in the run-up to Partition, killings on a massive scale took place in the Punjab, and later, to the east, between Hindus and Muslims in Bengal, which too would be sundered to create Pakistan's eastern wing.

These set the stage for the animosities of today, betraying the vision of the two nations' founders who had expected commerce and movement of people to continue as before, once the separation was effected.

Yet, the two nations only need to look to the history they shared before the bloodied Partition to know how much they jointly endured. The British presided over their own massacres in undivided India, including, most notoriously, in the Sikh holy city of Amritsar, where, in 1919, nearly a thousand unarmed Punjabis who had defied prohibitory orders were mowed down in an enclosed garden while celebrating a local festival.

To add insult to injury, General Reginald Dyer, who ordered the firing, was lauded by the British House of Lords.

Likewise, just four years before Partition, several million people perished in the Bengal famine of 1943, as a callous Winston Churchill ordered merchant ships operating in the Indian Ocean to be moved to the Atlantic. He did so to build up Britain's stockpile of food, all the while insisting that India export rice. If the famine was so bad, Churchill remarked when his officials pleaded on behalf of India's starving millions, then why was Mahatma Gandhi alive?

On balance then, if anything, Indians and Pakistanis ought to target their ire at the British colonialists who ruled for two centuries and drained their wealth.

Instead, both eagerly stepped into the Commonwealth from birth, and have continued to be its active members. Neither was there particular outrage when British Prime Minister David Cameron, during a visit to the Amritsar massacre site early last year, refused to apologise for Britain's actions, saying "it would be wrong to reach back into history".

On the other hand, India and Pakistan have turned on each other, spending huge slices of their budgets on defence, trying no end to trip each other up diplomatically, and otherwise. Bilateral trade is negligible, and what little there is, is mostly conducted through ports such as Dubai. Less than half a dozen direct flights a week connect them. Both nations seem unable or unwilling to learn from others that have also endured traumatic separations, but learnt to live with each other.

That is a pity because elsewhere in Asia, nations are learning to control even older animosities in the name of practical good sense. Japan occupied the Korean Peninsula from 1910 to 1945 but South Korea's late president Park Chung Hee, father of the current President, normalised ties with Japan as early as 1965. Some think President Park Geun Hye's tough attitude to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is prompted by criticism she faced on the stump because of her father's actions.

In so many ways, Mr Park's move set the stage for South Korea's current prosperity and technological advance. Indeed, in this year's Bloomberg Innovation Index, South Korea leads the global field, outranking Japan, the US and Switzerland too.

Likewise, it could be said that no country suffered more than China at Japan's hands. Yet, Deng Xiaoping found little embarrassment in asking Konosuke Matsushita, the richest Japanese of his time, to invest in the mainland as he opened up its economy. Today, there are 79 flights a week between Beijing and Tokyo, and 129 between Shanghai and Tokyo. Indeed, Chinese President Xi Jinping may note with satisfaction that getting in more Chinese tourists has become an important goal for Tokyo's public diplomacy division, even as it battles the fallout from Mr Abe's inability to mouth proper apologies for the war Japan pressed on Asia.

"Don't get mad, get even," the late Joseph Kennedy, father of the 35th US President John F. Kennedy, used to say. It is advice that is worth taking to heart.

India may feel satisfied that it has successfully "dehyphenated" itself from Pakistan in global thinking. It may even feel vindicated at seeing its economy steadily outpace its neighbour's year after year, widening the strategic gap with its nettlesome neighbour.

Likewise, Pakistan may take pride in the recent assessment by the International Monetary Fund that suggested its economy was turning around. But a hard and bitter peace is no substitute for a true flowering of ties. If not for wider Asia, at least for the sake of their own people, these two must at least continue talking.