Top economies around the world are affirming innovation as key to unlocking economic growth and more economies have developed capacity for innovation as highlighted by the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report.

Global spending on R&D reached a record high of almost US$ 1.7 trillion (S$2.25 trillion) in 2016.

The 2017 Global Innovation Index ranked Switzerland, Sweden and the Netherlands as the top three most innovative countries in the world. Singapore was ranked seventh, the only Asian country within the top 10. Just outside the top 10 were the Republic of Korea at 11th and Japan in 14th position.

Among the large economies, Japan remains one of the world's top research nations. Since 2000, in the fields of natural sciences, the number of Japanese Nobel Prize winners has been second only to the United States and on a par with the United Kingdom.

With a rich history of scientific discovery and innovation across the sciences and in electronics, robotics and automation, Japan is also home to almost 10 per cent of the world's most innovative companies.

Notwithstanding these achievements, Japan's own National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (Nistep) ranks the country ninth worldwide as a producer of highly regarded scientific research, falling two places from its 2016 survey. The 2017 Nature Index (Japan) similarly reported a nearly 20 per cent decline in Japan's share of scientific publications between 2012 and 2016.

Japan's predicament comes as a timely reminder for the rest of the world, especially those aspiring to be key hubs for discovery and innovation, to stay focused on what really matters and examine the critical elements that contribute to a vibrant and dynamic hub.

BREAKING DOWN BARRIERS

Japan is one of the world's highest spenders in R&D, investing 18.9 trillion yen (S$230.6 billion) in fiscal year 2016, approximately 3 per cent of its gross domestic product. However, its R&D budget has flatlined since 2001. Further to that, in FY 2017, the amount of grants to national universities was 10 per cent less than in 2004, leading to a reduction in permanent staff positions.

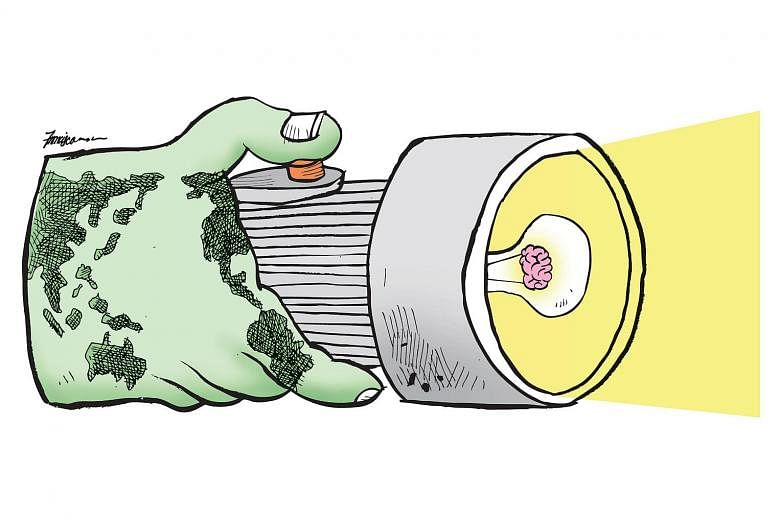

But funding may be the least of its woes. In an era where open science is becoming a worldwide trend in scientific research, Japan may be missing out due to its deep-rooted country centrism which contrasts sharply with the openness of the top innovative economies, including Singapore.

A 2015 report from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) urges the country to better integrate itself in "global innovation networks".

In 2014, only 0.4 per cent of Japanese research and development was financed from outside the country. The proportion of scientists who have immigrated to Japan is among the lowest in the OECD's 35 member countries. The result is a very low level of "international co-authorship of academic papers and co-patenting".

Perhaps the greatest factor could be cultural. Under the "hierarchical" Japanese system, most scientific positions are filled by word of mouth as senior professors often prefer to work with those they are already acquainted with. Young Japanese scientists who have gone overseas for exposure often find it difficult to integrate back into the system unless they have their own networks.

Japan also faces a long-term zeitgeist that everything needed to do research is already available in Japan. Thus, younger scientists typically do not see the "need" to venture overseas and, therefore, may miss opportunities to work with some of the other top researchers in the world and in a different research environment.

In 2009, Nistep reported that of 60,535 Japanese who earned doctorates in Japan from 2002 to 2006, a mere 2 per cent are known to have gone abroad for postdoctoral or other opportunities.

The numbers are similarly low for foreign students in Japan. A 2016 Nistep report revealed that Japan hosts 4 per cent of the world's population of foreign students and this is relatively smaller compared with other research-intensive large countries.

The US hosts the largest number of foreign students, accounting for 24 per cent, followed by the UK (13 per cent), France (7 per cent) and Germany (6 per cent).

While it is important for Japanese scientists to gain overseas exposure, the converse is just as critical in cultivating a conducive environment within Japan to attract international scientific talent. However, there are significant barriers to realising this.

Professor James R. Bartholomew, who specialises in the history of Japanese science and higher education at the Ohio State University, said "the biggest single challenge" to Japan's growth in science is language-related.

For example, some grant applications can be submitted only in Japanese. One principal investigator from research institute Riken describes how administrative meetings are held in Japanese and though his secretary can translate, she doesn't catch the subtle political nuances being discussed that impact his research.

DIVERSITY AND COLLABORATION

The Japanese government is fully aware of these challenges and is drawing lessons from innovation hubs around the world, with Singapore offering pertinent lessons as an Asian country.

Its Fifth Science and Technology Basic Plan in 2016 aims to make Japan the "most innovation-friendly country in the world".

The report acknowledges that Japanese science and technology has been "limited to our national borders and is thus unable to explore its full potential". It recommends key priorities such as the promotion of open science to better develop and secure intellectual professionals; reinforcing the "fundamentals" for its science, technology, and innovation efforts to promote diversity and career mobility; as well as building international collaborations to help address both domestic and international issues.

For a start, addressing the most fundamental hurdle in communication is a priority for the Japanese government. Japan is changing its internal systems to better serve foreign academics and students, such as publishing documents in English and solidifying English as the de facto language for scientific literature.

The report also recognises that "it is increasingly important to form and act in teams by bringing together people with diverse specialisations" to create new knowledge and value.

The next step is to build up a more diverse scientific community to complement its own scientific expertise. A range of initiatives such as the World Premier International Research Centre Initiative and the Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology grant was introduced in an effort to recruit a significant number of top international researchers.

Japan's universities are also being urged to take on a more global outlook for their collaborations and to recruit larger numbers of young and foreign academics.

The Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, which was established in 2011, plays a pioneering role in efforts to attract world-class scientists, with a requirement for 50 per cent of its faculty and students to be foreigners.

Under the exchange programmes by Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, which is the leading official body in coordinating and funding science and technology initiatives, Japan has hosted over 30,000 international researchers in the last few years. Efforts were also made to have more local researchers pursue their studies overseas over a longer period of time.

In line with these efforts, Japan is relaxing its immigration rules to speed up bringing in skilled professionals as permanent residents, and focusing efforts on the best people and institutions to bring in the best results.

Another fundamental change taking place in Japan has been to promote greater collaboration among universities, institutes and private companies, both within and beyond its shores, to embrace open innovation.

In the last decade, the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*Star) has certainly seen a step-up in collaborations with Japanese research organisations and corporations, and a number of them have established representative offices and R&D centres here respectively. In 2016, A*Star and the Osaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry signed an agreement to expand their cooperation to include open innovation.

Singapore values such partnerships. They add to the richness and diversity of our research and innovation ecosystem and create opportunities for both our research community and enterprises, as they do for the Japanese partners.

HOW TO STAY COMPETITIVE

More profoundly, they sharpen our appreciation of the critical success factors that keep our research and innovation hub attractive and remind us to continue to nurture and sustain this milieu to remain relevant and competitive.

Last year, the Committee on the Future Economy (CFE) presented its report. In his letter to the CFE, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said: "We cannot be sure which industries will perish and which will flourish. What is certain is that Singapore must stay open to trade, people and ideas, and build deep capabilities so that our people and companies can seize the opportunities in the world."

Next year, 2019, marks the bicentenary of Singapore's "founding" as a British entrepot city. Preparations are under way to commemorate this event and Singapore's long history and rich past as an open trading port. PM Lee has called on all Singaporeans in his New Year message to use this occasion "to reflect on how our nation came into being, how we have come this far since, and how we can go forward together".

One critical ingredient straddling the different time phases will be "staying open to trade, people and ideas".

•The writer is chairman of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*Star); special committee member of the Japan Science and Technology Agency Advisory Committee since 2014; and member of Japan's World Premier International Initiative Programme Assessment and Review Committee since 2007.