Reclaiming jobs for locals

We need to be more deliberate in reducing the number of foreign workers in domestic non-tradable sectors and freeing up these jobs for Singaporeans. This cannot be done in one step without creating large disruptions. But if we tighten the intake of low-skilled foreign labour in a determined and progressive manner over a few years, it would help drive restructuring in these industries, promote the adoption of technology and increase productivity, and help to sustain wage gains across a wider range of occupations.

There are about 620,000 resident workers in so-called "blue-collar" jobs - that is, service and sales workers, craftsmen, operators and labourers, but excluding clerical workers. The median wage of these occupations, including employer CPF, ranges from $1,500 to $2,350. Stripping out foreign work permit holders in the construction, marine shipyard and process sectors as well as migrant domestic workers, there are about 290,000 work permit holders in the rest of the economy - a majority of them working in similar "blue collar" jobs as the 620,000 resident workers. As a rough estimate, one out of three low-wage service jobs are taken up by cheap foreign labour. This cannot be good for local wages.

The demand for many domestic services like cleaning, maintenance and cooking is inelastic, and wages will have to go up if the number of foreign workers is reduced. The increase in wages, coupled with improvements in work conditions and prospects for a meaningful career, should gradually attract Singaporeans into these domestic services.

The transition will no doubt be challenging. Firms whose business models rely excessively on low-cost labour will have to exit. There may have to be some consolidation in these industries, such as retail and food and beverage.

It is likely that there would be local job losses in the initial phase. Moving from a low-wage equilibrium, such as the one we are in now, to a high-wage equilibrium, such as the one we aspire to, is always a tricky business.

The reclaiming of local jobs should extend beyond low-wage workers to the broad middle as well. I asked in my last lecture whether we should consider gradually raising the minimum qualifying salary for S Pass holders closer to the median wage of $4,500 from the current $2,500.

The reason is this: S Pass holders would be in mid-tier Associate Professional and Technician (APT) jobs. At $2,500 today, the minimum qualifying salary for S Pass holders is still significantly lower than the median gross income from work of APTs, which is $4,150 (including employer CPF).

I am not suggesting that S Pass workers should be drastically curtailed. Many of them are making valuable contributions to our economy and society. How could we have coped with Covid-19 last year if we did not have the many nurses here on S Pass? But when S Pass holders are available in such large numbers and paid around 30 per cent less than locals, there are two possible effects.

One, local wages are likely being depressed; and two, some of our ITE and polytechnic graduates are probably being competed out of these jobs.

Why not pay S Pass workers closer to the local median and let the market settle the employment profile? In some occupations, we might see an increase in local employment at better wages; in other occupations, where Singaporeans are unable or unwilling to enter, we will continue to employ the S Pass holders.

The scope for reclaiming local jobs at good wages is probably quite significant in the education and healthcare sectors.

These are two sectors that I cited in my last lecture as good candidates for becoming more exportable. According to MAS estimates, the health and education sector has an elasticity of substitution of 1.5, the highest among services industries. This means that if the wages of foreign workers in healthcare or education increase by 10 per cent, the demand for local workers as substitutes will increase by 15 per cent.

Not all jobs can benefit from technologically driven productivity growth but that does not mean that they cannot enjoy positive wage growth. Faster productivity growth in the tradable sectors, such as manufacturing and financial services, implies faster wage growth in those sectors. This increases demand for non-tradable services in the economy - such as food and beverage, healthcare and wellness, recreation and entertainment - which in turn means higher labour demand in these non-tradable sectors and higher wages.

Economists call this the Balassa-Samuelson effect - the mechanism through which higher wages in the tradable sectors lead to higher wages in the non-tradable sectors as well. As the American economist Richard Baldwin puts it, the Balassa-Samuelson effect is one of the best forms of redistribution. It is market-driven.

But in Singapore, we have blunted the Balassa-Samuelson effect through a large foreign worker intake in the non-tradable sector. A strategy of tightening foreign labour supply to reclaim local jobs will likely have cost implications across society. If there is consolidation in the industry to achieve greater cost efficiencies, then it would not be inflationary. If there are productivity improvements through technology, the cost pass-through would be limited.

But if the higher wages are not matched by higher productivity, then it would translate into higher costs, such as for healthcare and social services.

It may well be that the Government has to bear a larger fiscal burden to support some of these higher wages in the non-tradable sectors. That in and of itself is not a reason for perpetuating higher foreign worker dependency and low wages in these sectors. It means there are trade-offs that must be weighed carefully.

The key question for Singapore is: Do we want a dual economy with high inequality or a more inclusive society with higher wages but also higher costs? The Nordic countries have strict limits on low-wage foreign workers, which have facilitated a more equitable income distribution, low unemployment, and a sustained commitment to productivity and innovation.

If Singapore wants to be a bit more like the Nordic countries, it is not just government policies that would need to be adjusted but also the mindsets of businesses, citizens and workers.

Firms must reduce their reliance on cheap labour; citizens must be prepared to pay more for better quality services; and workers must be open to a greater variety of jobs.

Professionalising jobs

The key to understanding and beginning to address issues of income inequality is to look at differences in occupational wage - at as granular and detailed a level as possible.

Why do many occupations in non-tradable domestic services pay so little in Singapore? Many of these jobs are paid less compared to advanced country norms.

In some of these countries, professions that are not traditionally considered white-collar jobs are well-paid relative to median wages. They also have favourable career development paths.

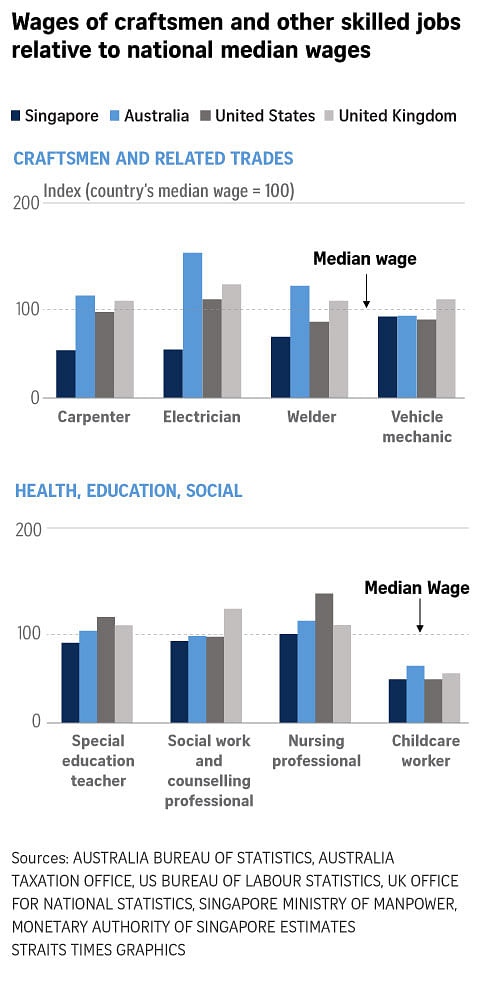

Let me highlight two categories of jobs: craftsmen and related trades, and health, education and social workers.

Consider wages in four craftsmen type occupations - carpenter, electrician, welder and vehicle mechanic. Let us compare the median wages of these four occupations across Singapore, Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom, relative to their respective estimated national median wages (represented by the horizontal line at 100).

In Singapore, carpenters and electricians are paid only 50 to 55 per cent of our median wage, while these occupations are paid at 100 per cent or more of the median wage in Australia, the US and UK. Our welders are paid better, at 70 per cent of the median wage, but still lower than in the other countries where welders are paid 85 to 125 per cent of the median wage.

Our vehicle mechanics are paid well, at 90 per cent of the median wage, roughly similar to Australia and the US. Perhaps it is because our cars are so expensive and we take care of them so well that we are prepared to pay our vehicle mechanics handsomely?

Let us now look at four occupations in the healthcare, education and social services sector - special education teachers, social work professionals, nurses and childcare workers.

Special education teachers are paid at 90 per cent of the median wage in Singapore, compared to 105 to 120 per cent of the median wage in the other three countries.

Social work professionals are paid at close to 95 per cent of the median wage in Singapore, not far from Australia and the US, where it is closer to 100 per cent.

Nurses in Singapore are paid at the median wage, in the UK and Australia they are paid 10 to 15 per cent higher than the median wage.

Childcare workers are paid well below the median in all four countries. This is somewhat strange given how much people everywhere value their children.

Perhaps more striking than the statistics are the real-life stories. A Singaporean lady who wrote to me after my last lecture related how her friend who is a doctor in London working at the NHS - National Health Service - found that the Polish plumber fixing her home heating system had a higher income than her; in fact, he also went on better vacations and was giving her vacation tips!

In Australia, visiting relatives, I have seen how the electrician drives to the customer's house in a car. He is well dressed, carries with him sophisticated equipment, and goes about his task professionally. The median wage of an electrician in Australia is more than 60 per cent above the national median.

Income inequality is high because wages in many skilled "blue-collar" jobs in Singapore are low relative to the median wage, compared to other countries. In Singapore, many of these professions are not well-paid or seen as promising careers: There is a social stigma against manual work and a reliance on low-wage foreign workers to fill these jobs.

One particular occupation that we should pay early attention to is long-term care providers. A 2018 study by the Lien Foundation on long-term care manpower benchmarked Singapore to four jurisdictions in Asia - Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea - all with high income, fast-ageing populations.

According to the report, despite concerted efforts to raise pay, redesign jobs, and improve skills and productivity, the sector in Singapore seems afflicted by constant churn. There is heavy reliance on foreign workers: About 70 per cent of direct care workers in Singapore's nursing homes, day-care centres and formal homecare settings are foreigners, compared to 32 per cent in Australia, less than 10 per cent in Japan, and 5 per cent in Hong Kong and Korea.

Direct care worker salaries here are lower than the tax adjusted long-term care compensation in the other four countries, where these jobs enjoy a high status.

Some efforts are under way to raise the status of skilled workers in domestic non-tradable sectors.

Take for instance, plumbers. A 10-year operation and technology road map has been drawn up to prepare plumbing firms for the new economy. The Singapore Plumbing Society, the National Trades Union Congress and seven small and medium-sized enterprises have undertaken to transform the sector.

Plumbing is skilled work; it must become a conscious career choice rather than a fallback option. In Australia, to become a plumber, there are minimum requirements, in formal certification, licensing, apprenticeship, and work experience. Maybe there is something we can learn here.

In fact, should we not set a goal: Make all jobs in Singapore professional. This is not a slogan. To be professional means being qualified and practising in a defined area of work, having expertise and a commitment to that area of practice.

Should we not all aim to be professional in our work?

Professionalising the jobs of plumbers, cleaners, gardeners and other skilled workers will require a change in the nature of these jobs.

We need to increase the skills content, leverage technology, improve business processes, and raise the quality of output. The cleaner of the future may be required to undertake basic maintenance, plumbing, changing of lights, landscaping and provide delivery services. This is already happening in London.

To professionalise all jobs, we could start by dropping from our vocabulary this category called PMET - professional, managerial, executive and technical jobs. If we cannot abolish it, then at least drop the "P" from the category: It suggests other jobs are not professional.

We should question the premise that all Singaporeans should aim to take up PMET jobs. Any population would house a distribution of skill sets, requiring a diversity of pathways that can lead to different types of excellence.

To be an inclusive society, we must value social and vocational skills as much as academic intelligence.

In European countries, skilled trades provide a middle-class lifestyle for many workers; these jobs provide dignity and social status.

We must do the same in Singapore. It is not just a matter of government policy, though policy can play a role. It is a whole-of-country effort.

Switzerland is a shining example of what it takes. At the question-and-answer session following my last lecture, Chng Kai Fong (Economic Development Board managing director) and I discussed Switzerland. What is it about Switzerland where every job is valued and there is such a premium on quality? A Swiss gentleman living in Singapore wrote to me after hearing the lecture.

Let me quote him: "Switzerland has cultivated for decades a tradition of formalised and certificated vocational training/apprenticeships. There is a diligently structured and formalised training course for almost every occupation, from nurses to plumbers, from salespersons to gardeners, from farmers to accountants, from truck drivers to bakers, from cooks to dental assistants, from instrument makers to hairdressers, from ski instructors to watchmakers and office clerks. There are about 250 vocational trainings that are certified by federal authorities."

Another Swiss gentleman had this to say: "For non-white-collar jobs to receive the appropriate recognition, it requires a triangular relationship: apprentice- company-customer. In Singapore, the above described relationship among worker-company- customer seems to be missing.

"Instead of industry players in the non-white-collar sectors taking a keen interest to develop a skilled workforce and hence raising the wages of the workers, the Government is the party doing the heavy lifting. It is telling that the Progressive Wage Model has to be mandated."

We must aim for a pervasive and persistent professionalism: a relentless quest for excellence in every job throughout the work life.

• Mr Ravi Menon will deliver the fourth and last lecture as IPS-Nathan Fellow tomorrow from 4pm to 5.30 pm on Facebook Live. Details are on the Institute of Policy Studies Facebook page.