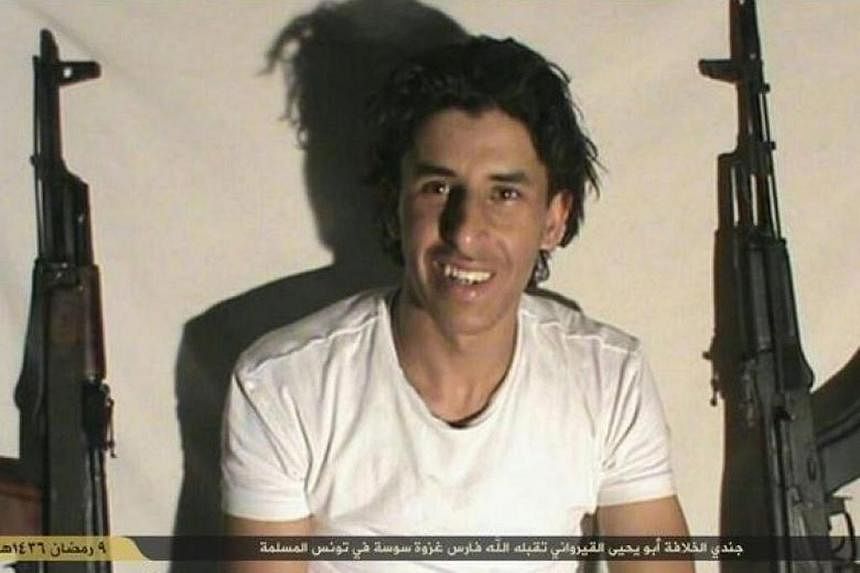

On the surface, Seifeddine Rezgui was an unlikely radical - a lover of hip-hop and football, unknown to Tunisia's security forces.

But to his classmates at Kairouan University, the man who gunned down dozens of mostly British tourists on a Tunisian beach last week was one of many they have watched over the years come to embrace a militant jihadi ideology.

"Seif was like any of the hundreds of students that come here: completely normal, until they transform into radicals," says philosophy student Hamdi Bilwafi, 29, who says he knew Rezgui.

It started with talk of Al-Qaeda, Mr Bilwafi recalls.

"Then he said he had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State (in Iraq and Syria, or ISIS) - he even wrote that on his Facebook page. I used to hear his friends challenge him about his decision."

Rezgui's attack, which killed 38 tourists in the coastal city of Sousse and was claimed by ISIS, was the second on foreign tourists in Tunisia in four months.

Long a source of militant Islamism abroad - Tunisians are one of the biggest groups of foreigners fighting in Syria and Iraq - the North African country is becoming one of its targets as well.

Kairouan, an ancient Islamic centre 60km from Sousse, has a symbolic resonance for radical groups; many in the city have Islamist sympathies. More significant, students say, is that chances to study and work there draw thousands, like 23-year-old Rezgui, from the impoverished and marginalised interior.

The centre of Kairouan looks like any other in Tunisia during the holy month of Ramadan.

Residents fan out into the streets in the evening after breaking fast to drink tea and watch Dlilek Mlak, the local version of Deal Or No Deal. Most of the thousands who come to the city move to its outskirts, where dozens of mosques deemed by the government as "outside state control" are suspected of spreading radical ideology.

In response to the Sousse attack, the government in Tunis has shut down 80 unregistered mosques around the country, out of an estimated 300.

But analysts say the move will anger even non-radical Islamists and is probably irrelevant, given that militants are more likely to network through the Internet and via personal relationships.

Mr Fadi Saidi, a member of the university's secular General Student Union, says social problems are to blame, such as unemployment and discrimination against those from poorer regions or those with darker skin. "Islamists feed on these divisions," says the 24-year-old computer science student.

"Our poor neighbourhoods are the supply line for the jihadis. Let's be honest - 80 per cent of Tunisian youth are on the path to militancy."

Students complain they cannot challenge a well-funded and powerful Islamist student union, of which they say Rezgui was a member. The group offers poorer students money for housing, food and even mobile phone credit.

"We don't have those kinds of capabilities," Mr Bilwafi says. "The Islamists can spread their ideology along with their bread - slowly."

Mr Tarek Kahlaoui, a researcher on jihadism in Tunisia, says cases such as Rezgui's show how the line between what is considered normal youth behaviour and radicalism has become blurred.

He says, for example, that right up to the attack Rezgui was using drugs, which is forbidden in Islam. He also posted on social media about his love for Real Madrid and breakdancing while also writing on his Facebook picture: "If being a mujahed is a crime, then I am a criminal."

Locals say Rezgui worked in Sousse as an entertainment organiser. This would have given him a view into the lives of foreign tourists that may have planted seeds of frustration, even while enjoying the music he once loved.

"It's like a split personality... He was evolving very rapidly - I estimate from early 2014 - (towards) an attachment to Salafi jihadi groups," Mr Kahlaoui says.

Mr Saidi, the computer science student, says: "Over a period of what felt like just two months, I saw him suddenly start to wear the short pants that Salafis wear and grow a beard. I asked him about his dancing. He said 'I repented, thank God.' Of course, he still was dating his girlfriend, which can't be acceptable to Salafis."

Many in Tunisia's secular elite blame the surge of radicalism on the rise of Ennahda, the moderate Islamist party which won the first election after Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was overthrown in 2011. Ennahda was later unseated by the secular Nidaa Tounes party. But Mr Kahlaoui says this overlooks the fact that Tunisian jihadis have played a large role in Al-Qaeda in Iraq since 2006.

Mr Michael Ayari, a Tunisia researcher with the International Crisis Group, says the elite must share responsibility because they have done little to engage with the Islamists or the one million voters who backed Ennahda.

"They need to discuss these problems, not hide them and maintain the discourse of a small elite," he says. "Make people dream - give them an alternative."

THE FINANCIAL TIMES