LONDON • Mrs Theresa May, Britain's new Prime Minister, and Mrs Nicola Sturgeon, the head of Scotland's regional government, have little in common: Mrs May wants to keep the United Kingdom united, while Mrs Sturgeon wants to break the country up by creating an independent Scotland.

Yet when the two leaders publicly shook hands for the first time over the weekend, Mrs Sturgeon concentrated not on their political differences, but on the single unifying bond between them: their gender. "I hope girls everywhere", wrote Mrs Sturgeon, would look at the picture of Britain's two most important politicians and conclude "that nothing should be off limits for them".

Undoubtedly, the last few months have been good for women in politics. Not only is the British government now led by a woman - the country's second female prime minister in less than three decades - but a woman, Ms Liz Truss, has also been put in charge of all of Britain's judiciary and courts, for the first time in a thousand years.

Germany, Europe's most powerful country, is led by a woman, as are Norway and Poland; indeed, the last general election in Poland was essentially a confrontation between two women. The head of the International Monetary Fund is a woman, and the next UN secretary-general - to be selected by September - is almost certain to be female as well. Furthermore, later this year Mrs Hillary Clinton has a very high chance of being elected president, perhaps on an all-female ticket which includes Senator Elizabeth Warren as her running mate.

Has the infamous but invisible "glass ceiling" which used to bar females from power finally been shattered? Yes, but only up to a point, for the progress of women in politics is still far too slow, far too hesitant and all too fragile.

First, the geography of gender equality remains uneven. In Africa, politics continue to be largely the preserve of men, usually in uniform.

In Asia, notable and very capable women have made it to the top, but in almost all cases on the back of a famous name or a powerful family connection. Benazir Bhutto in Pakistan, Indira Gandhi in India, the two Begums who between them dominate politics in Bangladesh, Mrs Megawati Sukarnoputri in Indonesia, Ms Yingluck Shinawatra in Thailand, the Philippines' Corazon Aquino who, despite her self-proclaimed "plain housewife" image, became Asia's first female president, or Ms Park Geun Hye in South Korea; all fall into this category.

Meanwhile, though as late as last year, Latin America's three biggest nations - Argentina, Brazil and Chile - were all run by women, only one of them still has a woman president now, while elsewhere on that continent, women languish on the edges of politics. And in the Middle East, the record of gender balance is dire: with the notable exceptions of Turkey and Israel, no woman has been either head of state or government throughout the region. So, what currently looks as a great advancement for women in politics is, in reality, still a limited and patchy phenomenon.

And even in those countries now run by women, the fact that a female is in charge does not necessarily translate into broader equality for women in public life. Germany has had a female chancellor for over a decade, but only 10 per cent of top civil service jobs in the country are being held by women, and women are under-represented in the regional politics of Germany's federal states. In Britain, the situation is not better: While progress has been made in promoting women to Parliament, gender equality in politics is still a pipe dream.

But what these bland statistics don't record is the myriad of other and more informal obstacles still confronting women who wish to enter politics. Research completed by the Centre for Leadership Studies at Exeter University in the south-west of Britain has found out that, almost without exception, women who wish to enter politics are being given parliamentary constituencies which are much harder for their party to win; men still scoop up all the nominations to "safe" constituencies which virtually guarantee them a seat in Parliament.

That has some serious implications for their future political prospects, since women are likely to contest a seat more times than a man before they succeed in being elected, and therefore enter Parliament at an older age. Mrs May is a classic example of this problem: she contested two elections before winning her seat on a third attempt, while Mr David Cameron, her predecessor, contested a seat only twice before becoming an MP. She took 19 years from the time she entered Parliament until she became prime minister at the age of 59; Mr Cameron required only nine years to reach the top position, at the age of 43.

The public is also merciless in the way it treats female politicians. As Margaret Thatcher, Britain's first woman prime minister, once ruefully remarked, "If a man speaks forcefully, he is deemed a politician of conviction, but if a female does the same, she is dismissed as hysterical".

A woman who reaches the top in almost any country now is either immediately described as an "Iron Lady" following in Mrs Thatcher's footsteps or as a scheming behind-the-scenes manipulator, a latter-day Chinese Empress Dowager Cixi; men, of course, undergo no such comparisons. A man seen sweating on an electoral campaign trail earns admiration for perseverance and dedication, but when German Chancellor Angela Merkel was photographed with sweat stains on her jacket, political commentators rushed to advise her on what brand of deodorant she should use in the future.

And then, there are the bogus extrapolations from the private lives of women to their political careers. Whether a female politician has had any children is considered supremely important; that was one of the key controversies in the recent contest between Mrs May and another female candidate for the post of British prime minister. The fact that she is childless is also a constant refrain dogging Dr Merkel in Germany. And that fact that she is unmarried is frequently mentioned in connection with President Park Geun Hye of South Korea.

Why only women are subjected to this scrutiny is never explained. But the explanation is almost entirely sexist, and probably starts from an assumption that a childless woman is a peculiar one, a person with a supposedly incomplete life experience. There is also the implicit assumption that a woman who is either single or childless is obsessive about politics. The fact that generations of men were obsessive about politics to a far larger extent is regarded as immaterial; men are assumed to be able to leave their children in the care of maids or invisible wives, but that's not an option regarded as available to women politicians.

Yet probably the most perverse sexist stereotype about women in politics is one currently pushed, paradoxically, by some feminist campaigners, who suggest that if the world was ruled by women there would be fewer wars, and that the current wave of women leaders is due to the need to "clean up the mess created by men".

German writer Mara Delius invented a new term of "femokratie" to describe the coming rule of feminine democrats. And she describes them as post-modern saviours "in trouser suits and rubber gloves", equipped for the political sweeping which lies ahead.

But much of this is nonsense. For while there is plenty of evidence that macho cultures contribute to conflicts, there is no evidence that women heads of government are more peaceful than men in similar positions. Indira Gandhi in India and Golda Meir in Israel didn't shirk from wars, and neither did Margaret Thatcher. Nor is there any compelling scientific evidence that women are inherently better at administration.

But what is undoubtedly true is that nations which don't harness the political talent of half of their population end up poorer for it. And it's equally obvious that women will only achieve true equality when nobody - neither voters, nor the media - views them as a special case in politics.

Judging by what is happening to Britain's Mrs May at the moment, females are still a long way away from that equality.

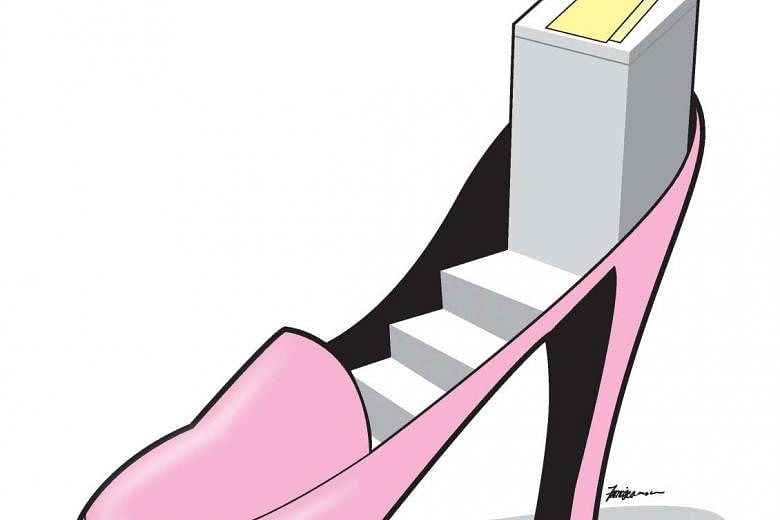

For as Britain's Prime Minister engaged in critical talks about the country's unity with Scotland's leader, news agencies preferred to concentrate instead on comparing the shoes of the two women.

Mrs May wore red stilettos and Mrs Sturgeon blue ones, if you really must know.