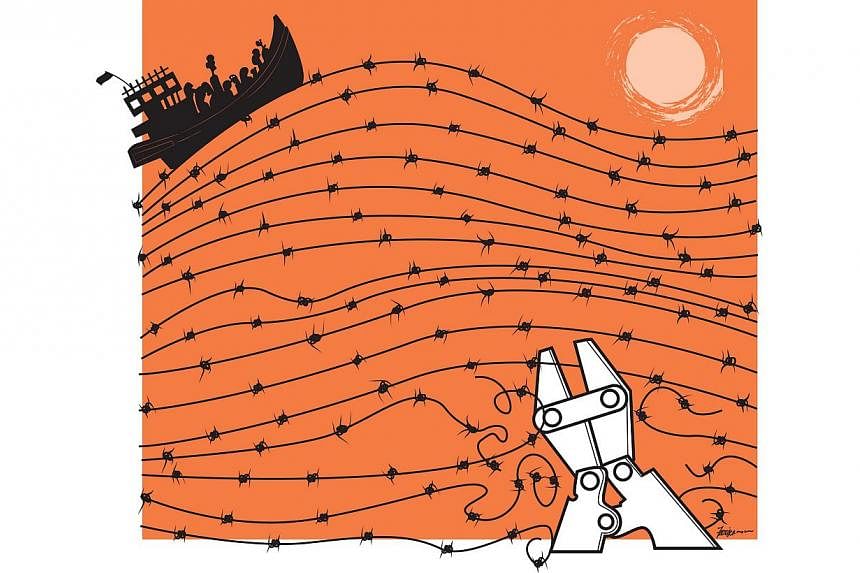

FOR the moment, humanity has triumphed: The Thai, Malaysian and Indonesian governments have done their humanitarian duty towards the boat people from Myanmar and Bangladesh stranded on rickety boats in the Andaman Sea and the Strait of Malacca.

But those governments are right to say they cannot be expected to bear this burden forever. They are also right to say the problem of the boat people is bound to get worse unless its root causes are addressed and the legal regime that handles such situations is radically reformed.

It is worth recalling some fundamental facts about these tragedies - facts that usually get drowned out when a crisis of this sort erupts.

First, the phenomenon is not new: The coastlines of South-east Asia and those of the Mediterranean between Africa and Europe, for example, have been subjected to large influxes of "boat people" for centuries. What has changed is the ability of nation states to monitor their coastlines and survey the high seas.

Furthermore, far from indicating a failure of immigration controls, the rising number of boat people comes precisely because global immigration procedures are tight. In an age of electronic detectors and electrified fences, crossing land borders is getting more difficult, or just as dangerous as using sea routes.

And contrary to received wisdom, what prevents would-be migrants from using air transport is not the price of tickets but, rather, the fact that countries have outsourced immigration controls to airline staff.

The real hurdle for a would-be illegal immigrant trying to use a plane is not the immigration officer at the airport of disembarkation but, rather, the checking- in clerk at the airport of departure, who would refuse to issue a boarding pass if there is the slightest suspicion that the passenger may be denied entry at his destination.

So, illegal immigration takes to the waters because other methods of travel are even less inviting.

It is also worth remembering that criminality has always been a part of this illegal migrant flow. Some of the traffic in Chinese labourers or Japanese women intended for prostitution throughout Asia during the 19th century was seaborne, mostly illegal, and organised by mafia-like networks.

And the same applied to one of the biggest European migrations of the 19th century: the large number of Jews who fled Russia. Many of those who ended up in Britain did so only because they were cheated by criminal boat operators who charged them for ship passages across the Atlantic to America, but which landed them instead on English shores.

Still, the truth remains that we are entering a new age of mass migration pressures, which will test our sense of fairness and morality to the extreme and even overhaul our concept of national borders. One reason for this is the growing gap between poor and rich nations, which is no longer measured in just statistical numbers, but also in the many generations of backwardness - unlike their predecessors, people now are aware of their poverty and helplessness.

The collapse of existing states in the Middle East merely adds to this refugee crisis. And rising water levels as a result of climate change could produce a refugee crisis of unprecedented proportions, much of it acted out on the high seas.

Yet that does not mean that governments are impotent. Much can be done by adopting sensible new policies and tightening global cooperation.

The starting point should be an admission that while some of the pressures that prompt people to board rickety boats in search of a better life are beyond anyone's control, many are the result of botched government policies that are eminently preventable.

It is immaterial, for instance, whether one accepts the official version from Myanmar officials that the Rohingya are just immigrants from Bangladesh and have nothing but an "invented identity", or whether one believes the claim of the Rohingya themselves that they are the descendants of ancient Persian and Arab traders. The reality is that their forced resettlement inside Myanmar and the tightening noose of restrictions imposed on them by the authorities have directly contributed to the current refugee crisis.

Cross-border dialogue

ASEAN governments may wish to continue adhering to the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries, but they will have to accept that ignoring major lapses in governance in one country has serious consequences on all its neighbours. A vigorous cross-border dialogue about good governance has never been needed more than now.

And this dialogue needs to go beyond old cliches whereby Western nations are the only ones that one can safely criticise in public. If a Western country chose to segregate its Muslim residents and encourage their departure, the howls of protests around the world would have been deafening, and rightly so.

But when Myanmar did precisely that for decades, there was largely silence. Is this myopic, selective response either acceptable or sensible?

Governments around the world should also get better at emergency planning for seaborne refugee outflows: The Rohingya refugees first started arriving in Bangladesh in 1982, when a Myanmar law refused to recognise them as one of the 135 "national races" of Myanmar.

International refugee regime

BUT many thousands of boat people will continue to perish unless the world's governments accept sweeping, profound changes to the way we tackle the problem.

The current international legal regime on refugees was devised for a period when the number of people crossing borders was relatively small and the distinction between refugees and migrants was clear. But the system is now being largely abused as another method for immigration.

The current legal regime also decrees that the country on whose territory refugee seekers land first is stuck with them for ever. Since this places a disproportionate burden on the nations closest to immigration flows, states have a vested interest in pushing migrants farther afield, rather than rendering them immediate assistance.

The result is, perversely, an even greater accidental loss of life as well as greater cruelty, as refugees are passed from one authority to the next in order to maintain the fiction that they do not exist. And that breeds a further layer of corrupt middlemen and bribe- seeking officials.

Shared quotas

WHAT is required is the introduction of a new system of temporary quotas, with countries sharing the burden of refugee settlement in a more equitable manner.

Such an arrangement can only be voluntary, but countries which accept refugees should be given a cast-iron guarantee that the settlement of such people will be truly temporary - burden sharing must be a continuous, rather than a one-off, project.

That, in turn, will require greater cooperation between governments in documenting refugees.

At the moment, many boat people either do not have their identity papers or they destroy them in order to make it impossible for governments to send them back to their country of origin. Yet the advent of biometric databases should make it relatively easy to identify them and cooperating on the proper identification of boat people should be a priority for all global and regional organisations.

And meanwhile, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees should spend less time behaving like a non-governmental organisation promoting greater acceptance of refugees, and more time in coordinating innovative approaches to the handling of current refugee flows.

The more this happens, the higher the chances will be that refugees will be rescued from drowning at sea.

But ultimately, what this debate requires is less emotion and more logic, a bit less emphasis on morality and a bit more on the realities.

It is simply not true to suggest that a country that accepts all boat people washed upon its shores is somehow more merciful than a country that does not. A good case can be made that the easier it is for boat people to land, the more this encourages further flows and further misery.

Nor is there such a fundamental distinction between countries that accept boat people for settlement and those that refuse them entry but agree to pay for their upkeep. Japan did the latter during the Vietnamese boat people exodus of the late 1970s and it performed a valuable humanitarian service.

For when all is said and done, the truth remains that while governments have to uphold the basic responsibilities of humanity, they also have to, as their first priority, look after the welfare of their own citizens and take into account the growing opposition in all developed countries to further, large migration inflows.

This is not a morality tale, but a painful debate between the desirable and the possible.