Europe is in a race against time. After six years of economic crisis, extremist political parties are entrenched across the continent. Set against that, the European economy is in better shape than for some years. The question is whether economic optimism can return quickly enough to prevent the bloc's politics slithering over the edge.

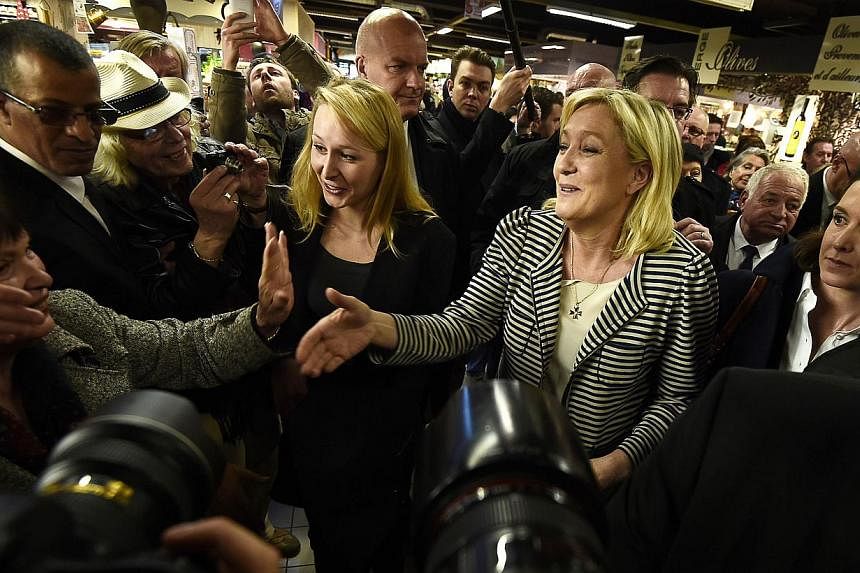

The signs of political rot are evident. In France, the far-right National Front (FN) notched up about 25 per cent of the vote in regional polls on Sunday. Prime Minister Manuel Valls has warned that FN leader Marine Le Pen could actually win the presidential election in 2017. That same year, Britain could vote to leave the European Union. And by then, the single currency could also be well on the way to disintegration, with Greece out and Italy heading for the exit.

But while the political signals are still bleak, there are grounds for economic hope. Spain and Ireland, which have suffered most from debt crises and austerity economics, are finally recovering. Spain is expected to grow at 2 per cent this year and unemployment in Ireland will drop below 10 per cent soon. Even Greece had experienced a return to economic growth. More broadly, the combination of lower oil prices, a falling currency and monetary easing by the European Central Bank should deliver a considerable stimulus to the EU economy this year.

A return to growth might give Europe some breathing space and head off the chance of political disaster. The difficulty is that, although there is a link between economic hardship and political extremism, it is not precise. The collapse of the political centre can be a delayed reaction to economic woes - and can kick in just as the economy is recovering. To choose a particularly doom-laden example: the Nazis took power in 1933, after the worst of the German depression was over.

A depression, or a prolonged recession, does more than create economic hardship. It also serves to discredit mainstream ideologies and to whip up anger against political elites - and those effects can last well beyond the point of economic improvement.

Also, a sense of economic crisis is only one source of support for the political extremes in France. Fear of immigration and anger about elite corruption have bolstered the FN - and driven the rise of fringe political movements in Italy, Germany and Britain.

A return to growth is also unlikely to address completely the EU's sense of economic malaise.

Across Europe there is a fear that nations have been living beyond their means and may have to accept a permanent downward adjustment in living standards. In countries such as Greece, Portugal and Ireland, that adjustment took place in a swift and brutal fashion because of the financial crisis - and has resulted in cuts in nominal wages and pensions.

But even countries that escaped the worst of the crisis are going through an adjustment in living standards that is hitting the young particularly hard. Rates of youth unemployment are frighteningly high in some countries: above 50 per cent in Spain, nearly 40 per cent in Italy, 23 per cent in France and 17 per cent in Britain. There is a fear that the rising generation will live less secure lives than their parents.

Even with quite strong growth, there is disillusionment with the political establishment. Britain's general election in May will likely see a record low share of the vote for the parties that have dominated post-war politics, the Conservatives and Labour, and strong gains for nationalist parties in Scotland and England.

In Italy all of the leading opposition parties are in favour of pulling out of the euro - a remarkable trend in a country that has traditionally been fervently committed to the European project.

Hungary is ruled by a semi-authoritarian administration and has an overtly racist party on the rise.

But it is France that matters most. If Britain left Europe or Greece quit the euro, the European project would stagger on. But the election of Ms Le Pen as French president would in effect spell the end of the EU.

To avoid ratcheting up political tensions in France, Brussels has just allowed its government once again to break EU rules on budget deficits. The fact that the FN has not made a decisive breakthrough in this weekend's elections will feed the hope that an economic recovery will arrive, just in time, to stabilise the country.

But ultimately France and the other EU members need more than a modest uptick in growth to restore the health of their political systems. They need mainstream politicians who can paint a convincing and optimistic picture of the future. So far, there is not much sign of that.

FINANCIAL TIMES