LONDON • Europe is "at war" with international terrorism. So says French President Francois Hollande, who has dispatched his country's aircraft carrier to the Middle East to "destroy" the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) terrorist organisation.

So also say France's closest European allies, such as British Prime Minister David Cameron, who vowed to follow a "comprehensive strategy" of bombing ISIS militants "wherever they may be". Even Pope Francis appears to agree with Europe's current warlike language; the universal head of the Catholic Church has said that the recent terrorist attacks in Paris "are part of a Third World War".

Yet much of this menacing drumbeat is just diplomatic noise, designed to mask Europe's impotence. Still, if not properly controlled, such bellicose sounds can have very grave consequences.

The current turn of events is not without its ironies. When terrorists hit at multiple targets in the United States on Sept 11, 2001, killing on a far larger scale than the casualties suffered recently by Paris, the Europeans expressed their compassion, but also urged caution.

US President George W. Bush was criticised for declaring a "war on terror", partly because the term was hopelessly imprecise, but also because, as European armchair strategists led particularly by those in France pointed out, a war on terror became a Bush obsession, one which ultimately overshadowed and skewed almost everything else the US did in the world.

Now, however, the French are consciously repeating Mr Bush's alleged mistakes, and at almost every step.

Not only is this evident in the language of war which President Hollande uses on a daily basis, but this also emerges from the legislation France is implementing at home. The "state of emergency" imposed on France for the next three months is more draconian in its provisions than America's Patriot Act which Mr Bush signed in 2001, a law which a French prime minister at that time criticised as "causing the US to lose its moral compass".

And, just as the US rushed into Afghanistan and subsequently into Iraq, so France now appears poised to leap into an ill-fated military operation in Syria.

FEW STRATEGIC GAINS

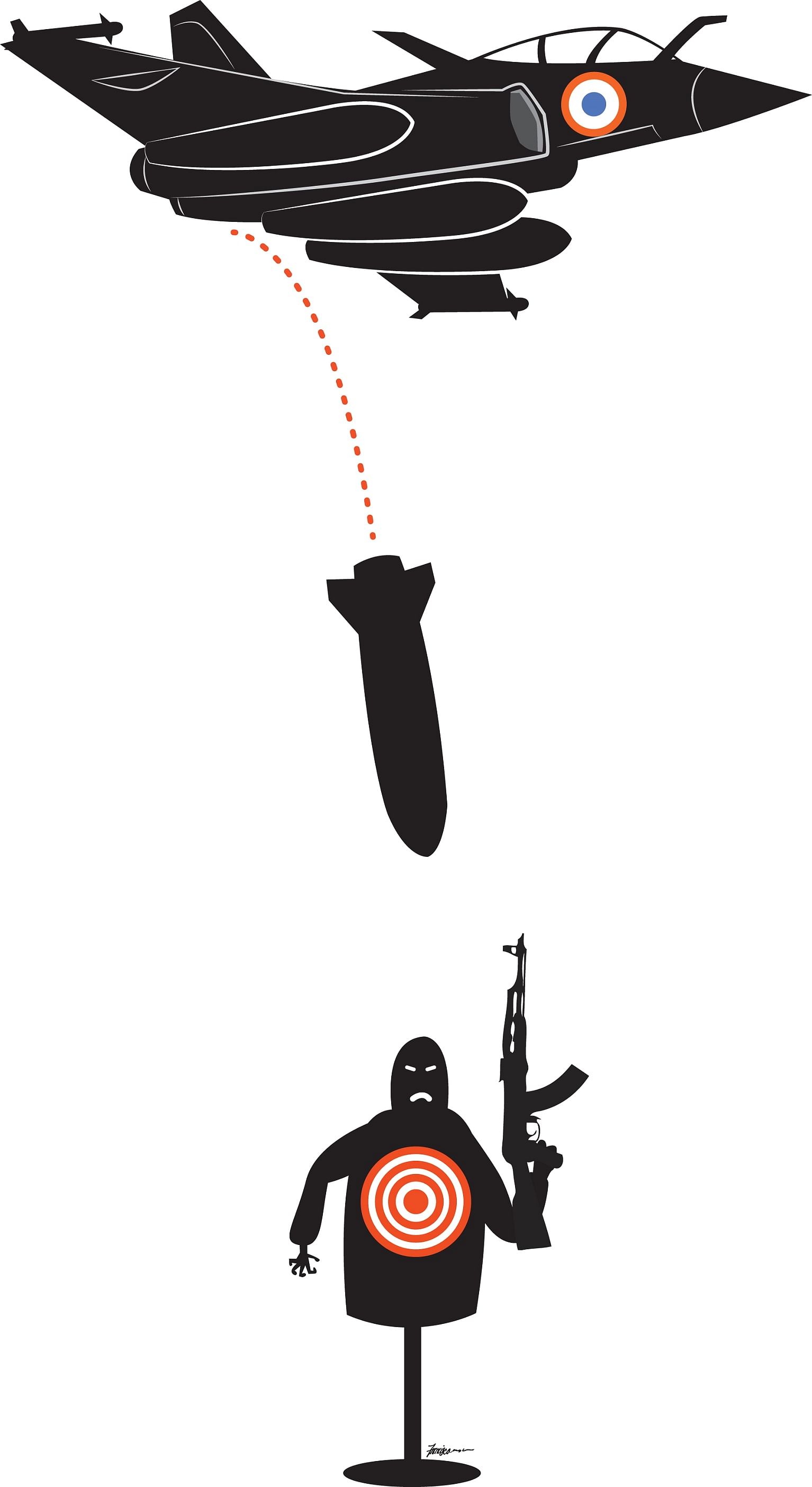

Immediately after the recent Paris bloodshed, French aircraft unleashed a heavy bombardment of Raqqa, the city in Syria which serves as ISIS' unofficial "capital". As an exercise in symbolism, the move was perfect: it reminded everyone - and particularly the French electorate - that France is capable of striking back, and that the terrorists who masterminded the Paris murders cannot retreat to safe hideouts in the Middle East.

But in practical terms, neither this nor the subsequent French attacks made the slightest bit of a strategic difference. For just about the only military asset which is not missing in Syria is air power: Over the past year, a 10-nation coalition led by the US has conducted at least 3,000 air strikes against terrorist installations in Syria, and that figure does not include the Tomahawk missiles fired from US ships in the area.

Yet none of this can "destroy" ISIS - as Mr Hollande desires - unless someone is prepared to put troops on the ground, with the objective of occupying territory and preventing the terrorist organisation from regrouping. And the chances of that happening are virtually nil, for the US is the only power capable of sustaining such an operation, and President Barack Obama has ruled it out.

Undeterred, however, Mr Hollande will be spending this week on a shuttle-diplomacy tour of the US and Russia, trying to persuade the presidents of both nations to join hands in Syria.

In theory, that's precisely what the world requires; Mr Hollande will be strengthened by the resolution which the United Nations Security Council adopted over the weekend, which provides the legal basis for more coordinated military action against ISIS.

In practice, however, the budding alliance between Russia and the West which Mr Hollande wants to create will produce few of the strategic benefits France expects, but inflict serious consequences on European security.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has deployed his aircraft to Syria not because he cares so much about the menace from ISIS, but because he wants to protect Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad and Moscow's old ally, and because he wants to make it clear to the West that no conflict in the Middle East can be resolved from now on without Russia's participation. His objective is not to join hands with the West in eradicating terrorism, but to re-establish Russia as a power, with its own "satellites" and spheres of influence.

By granting his wish - as France now wants to do - the West would vindicate Mr Putin's strategy of forcing his way to the top negotiating table. The West would also be sacrificing Ukraine, parts of whose territory were annexed by Russia last year; it is very difficult to see how the Russians will cooperate with the West in the Middle East while still being content to be subjected to Western economic sanctions, imposed as a result of the Ukraine crisis.

So, as part of a deal over Syria, the sanctions will have to go. In effect, the message from the West will be that territories are up for barter in return for concessions "big powers" make to each other. That's what happened in 1945 at the end of World War II when Europe was partitioned; that is precisely the model that Mr Putin is now openly invoking.

HARDER FIGHT AT HOME

A good case can be made that countries have interests rather than sentiments, and that if Ukraine has to be sacrificed in order to defeat a deadly terrorist enemy in the Middle East, so be it. Russian airplanes have now started bombing ISIS targets, and Moscow can increase its firepower; as far as France is concerned, nothing else matters at the moment.

But in reality, the Russians are only likely to make the Syrian situation worse. The sight of a Russian-Western alliance which maintains a Shi'ite-controlled Syrian government in power with the additional help of Iran will infuriate just about every Middle Eastern government. It will also act as the best recruiting agent for ISIS and other terrorist organisations: The narrative that the West is now engaged in a "crusade" against Islam will sound more plausible. In effect, France is proposing to pay far too high a price for a very improbable advantage.

Overall, talk of waging a "war" in the Middle East - a war which largely consists of dropping bombs in various places from a safe distance without putting Western or Russian soldiers in harm's way - is a distraction from Europe's real task, which is to isolate the men of violence now in Europe, dismantle domestic radical networks and work harder at integrating alienated Muslim minorities.

That requires time, money and a great deal of patience - none of which is a commodity Europe currently has in abundance. So, European politicians will continue to be tempted by the more glamorous talk of a "war against terror" in the Middle East.

Yet, as Mr Jan Techau who runs Carnegie Europe, a prominent security think-tank, aptly remarked recently, "nobody has the actual or the political capital and the strategic savvy to pull off a more activist role for Europe".

Europe's current noise-makers for war "will look silly", he predicts. "The Islamic State will rejoice. Local potentates will continue to wage war against their own populations. The next terrorist attack will come. And then, the discussion will start all over again."