Every year, tens of thousands of Singaporeans fail to pay fines for offences ranging from breaches of town council rules, to illegal parking, speeding and other traffic-related matters, to failure to pay utility bills.

After repeated reminders go unheeded, a warrant of arrest is issued by the courts and that is fed into a police enforcement database.

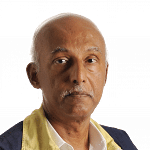

That is what happened to Madam Josephine Savarimuthu, 73, who had breached town council rules over wrongful placement of potted plants. Her initial fine was $50 but ballooned to $400 by the time she settled the bill on March 7, which included court legal fees.

Madam Savarimuthu was arrested on March 4 when she went to Ang Mo Kio South neighbourhood police centre to report a lost pawn ticket. The police officer discovered an outstanding warrant of arrest for her, issued by the court last year as she had failed to attend court in relation to town council summons.

So on that Saturday, the police offered her bail. She refused. She was then taken to a police station and from there to court. After the matter was processed by the court, she was escorted that same day to Changi Women's Prison - with handcuffs and leg restraints on her.

After being remanded over the weekend, the same restraints were used on her on Monday morning when she was conveyed to the State Courts from the prison to be dealt with for the offence. Her daughter, Madam Gertrude Simon, 55, bailed her out then and on the following day, the fine was settled.

But the manner of her treatment subsequently drew debate. The incident came to public attention after Madam Simon wrote in to The Straits Times Forum to register her unhappiness over the way her mother was treated and to call for law enforcement officers to exercise flexibility in their treatment of elderly folk.

The case actually raises questions about the treatment of two different groups of offenders. The first are elderly suspects in custody, whose numbers could swell in the coming years given the rapid ageing of the population. The second are those guilty of municipal offences and who have, as a result of non-payment of fines, had a warrant of arrest issued against them.

OF FINES AND ARRESTS

Those who commit municipal offences are of all ages and backgrounds. Currently, the police execute warrants of arrest triggered against such defaulters by a host of agencies, such as the Housing Board, Land Transport Authority (LTA) and town councils.

In 2015, the caseload for departmental and statutory board charges and summonses handled by the State Courts rose to 143,700, from 116,865 in 2014. While these figures include charges not handled by police, it stands to reason that at least a share of these cases involve police enforcing warrants of arrest against individuals, as in the case of Madam Savarimuthu. The question is whether this is the best way to deal with such offenders.

There is also the matter of resource allocation, as current process takes up scarce police resources and incurs court costs. Alternative options are worth exploring, especially as other countries, such as Australia, have found different means to deal with such offences.

In the state of New South Wales (NSW), for example, most minor offences would not result in an arrest warrant, a police spokesman for the state said in response to questions from The Straits Times. "Ultimately, the non-payment of fines sees the matter fowarded to the State Debt Recovery Office. They take action to recover the money and then are able to cancel drivers' licences in NSW, for instance in the case of driving offences," he said.

The State Debt Recovery Office (SDRO) administers the NSW fine enforcement system and is responsible for the receipt and collection of outstanding fines and penalties. These fines are for miscellaneous minor infringements, such as parking offences, failure to pay bills like ambulance fees or election-related breaches.

The SDRO is armed with remedies such as garnishing the sums payable from the offender's employer or placing a charge on property and, if such actions fail, then an order for community service is issued.

No equivalent of the SDRO may be justified here in cost-benefit terms but it stands to reason to consider a scenario where agencies like the town councils are empowered to deal with municipal breaches on their own, armed perhaps with remedies similar to those made available to the SDRO. After all, it seems more appropriate for municipal offences to attract penalties proportionate to the nature of the breach.

A review of current processes could also help to shift the burden of enforcement action away from the police and free them to focus on more serious challenges to safety in the face of new security threats.

SENIORS IN TROUBLE

Singapore is not the only country grappling with the issue of senior citizen arrests. In Britain, police arrest some 40 senior citizens a day on average, according to 2010 figures reported in the Daily Mail.

"Their crimes range from failing to pay a fine for overfilling a wheelie bin to not wearing a seat belt or chopping a neighbour's hedge without permission," the newspaper reported.

In Singapore, comparable data is not currently available publicly but The Straits Times reported earlier this month that the number of elderly prisoners has almost doubled in the past five years. The Singapore Prison Service has even retrofitted some prison cells with senior-friendly features like grab bars and handrails. With the ageing of society, the issue of how the elderly should be treated while in police custody gains added significance and urgency.

In the case of Madam Savarimuthu, the prisons officers who handcuffed and used leg restraints on her - virtually maximum-security restraints - were following procedures that have likely evolved over time.

There was one case each in 2007 and 2008 in which remandees attempted to escape.

In 2007, two accused persons broke free from police escorts near District Court 26 in the basement level. They were recaptured within the premises. In June 2008, two accused persons who were not handcuffed fled from the court lock-up but they were promptly apprehended within 100m of the lock-up. Two days later, the pair were back in the then Subordinate Courts, appearing with hands cuffed and legs shackled.

In today's post-Mas Selamat era, the mantra seems to be: Better to be safe than sorry - to a fault. Singaporean terrorist Mas Selamat Kastari escaped from Whitley Road Detention Centre in February 2008 and was on the run before being arrested by the Malaysian Security Branch in April 2009.

Now, the standard operating procedure (SOP) seems to be for prison inmates and remandees to be handcuffed and shackled not only to ensure secure custody but also to prevent them from harming themselves and others, including the officers. Also, it can be risky to expect ground officers to be able to discern quickly the risk level of a person in custody merely from the nature of their offence or age.

The challenge is for the authorities to find a way to relax procedures for minor offences and elderly offenders without raising risks significantly.

Criminal lawyer Josephus Tan argues for a "calibrated" approach in dealing with the elderly, including making provisions for someone to assist the senior in custody. This is "not just a legal issue but a social issue", he said. "There is no 'one size fits all' but what we see are a sign of things to come, given that we are an ageing society."

Retired award-winning social work professional K.V. Veloo urged prisons and police to start developing an SOP on how to deal with seniors that covers each stage of the process - from arrest, interrogation, confinement in police or prisons' remand to court appearance and disposal.

"I will go a step further: They should be treated as in the case of juvenile offenders under the Children and Young Persons Act, which provides protection and care of such young people. The hallmark of a caring society is seen in how it treats its weakest members," said the former chief probation and after-care officer.

It would also be more ideal if the rule is not to use security restraints on elderly offenders and those involved in minor cases but allow officers the discretion to do so.

That is especially so for the elderly, who may be facing their first run-ins with the law after long years of law-abiding existence.

On this issue, a review is timely.