LONDON • Slowly and nervously, Europeans are returning to normal life. Public transport is resuming, albeit with many restrictions. Some borders are reopening, although this is hardly a continent-wide phenomenon. A few are tiptoeing back to their workplaces. And grandparents now have the chance to hug the grandchildren they have not seen for months.

But in many respects, Europe will never return to the way it was. The health crisis has accelerated several negative trends that have buffeted the continent over a longer period and will force European governments to confront the challenges they have spent many years trying to avoid.

A logical argument can be made that, as regrettable as the current circumstances may be, forcing the Europeans to come to terms with their longstanding structural problems is not necessarily a bad idea.

But the snag is that the task of confronting the continent's biggest challenges is coming just when governments are at their weakest, and when the economic setting can hardly be less inviting.

The most important problem - although at least for the moment, also the least noticeable - is that of the enduring legitimacy and relevance of existing European governance structures.

The ability of European governments to answer the real needs of their electorates has, of course, been a recurrent challenge for Europe's politicians for years; just think of the popular rebellion of the so-called Yellow Vests in France, the British referendum to leave the European Union which amounted to a wholesale rejection of an entire political elite, or the meltdown of traditional political parties throughout the continent.

Still, the pandemic has brought this anti-establishment wave into sharp relief. And although both electorates and politicians are still too shell-shocked to say so now, the day of reckoning will come, and some governments and political structures will be dismissed as simply not fit for purpose.

COVID-19 RECKONING

For how can one adequately explain the massively different coronavirus mortality figures in places such as Germany, which had only a fifth of the deaths recorded in Italy, Spain, France or Britain calculated as a percentage of population, or the fact that the poorer eastern Europeans performed much better on every health yardstick than the far richer western half of Europe?

No doubt there are scientific variables which can explain existing disparities, such as population density and age structures, or the timing of the pandemic, which varied from country to country.

Be that as it may, it is already clear that when the day of reckoning arrives, individual European governments will be judged according to how they performed during the health crisis.

That is good news for Germany, where populists who only a few months ago were rising rapidly in voters' preferences are now in the doldrums, as established leaders such as Chancellor Angela Merkel prove the value of experience.

But it is bad news for countries such as Italy, France, Britain and Spain, where ruling politicians will be charged with not performing as well as expected, however unjust such accusations may be.

For in politics, nothing succeeds as well as success, and most European leaders are perceived to have failed. Furthermore, the countries that were already suffering most from the wave of populism and a rejection of established politics are also those likely to experience the most painful soul-searching when the health crisis is over. This is the case in Italy, where the rickety ruling coalition enjoyed an initial popularity boost, only to be threatened again by the Northern League, a populist anti-immigrant movement. It also applies in Spain, where a centre-left coalition formed after three inconclusive general elections is unlikely to hold together as the country's big economic downturn hits.

FORCE MULTIPLIER?

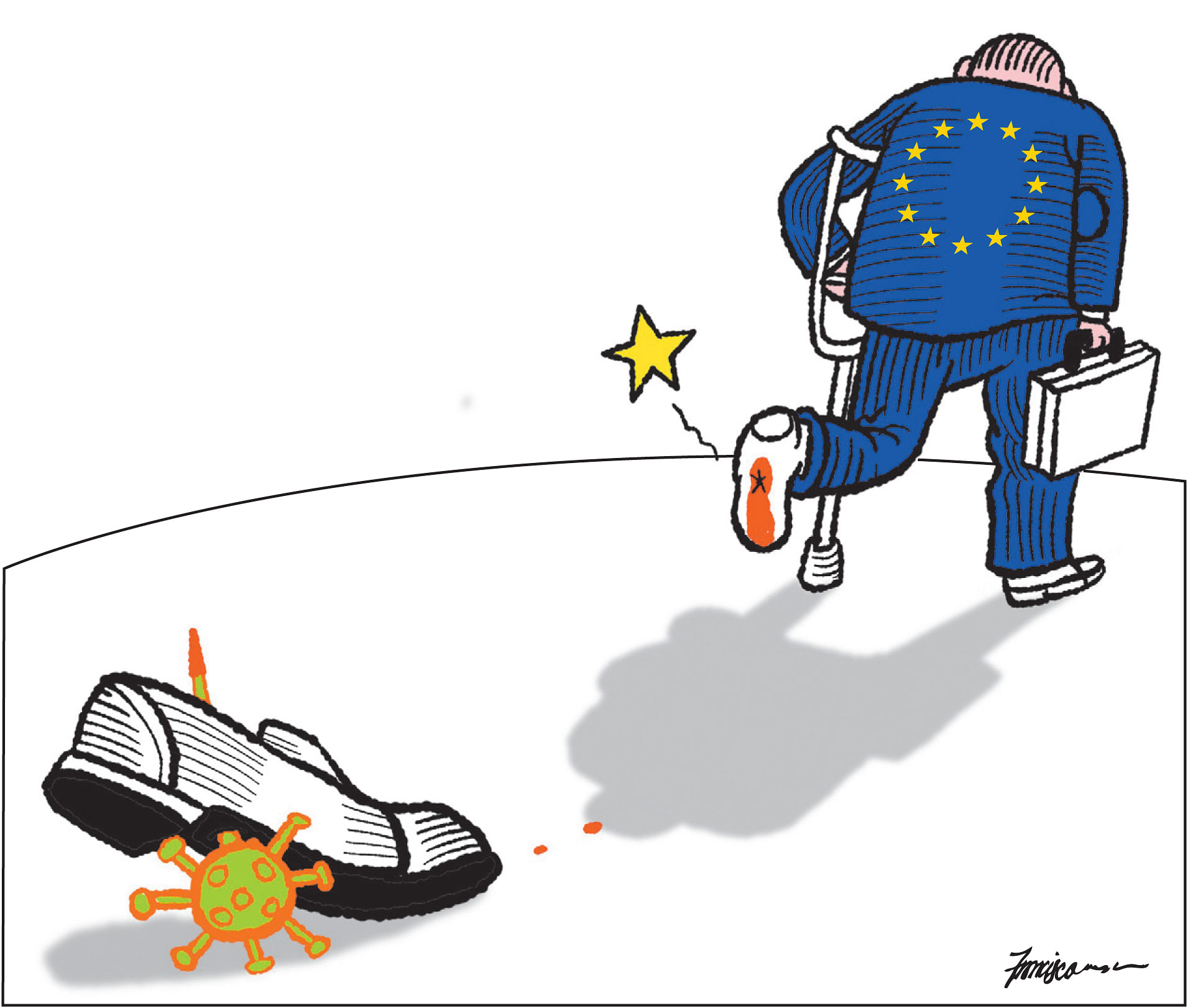

The EU as an institution will also not emerge well from this trial. Yet again, the charge may be unjust: Primary responsibility for healthcare belongs to individual member states rather than the EU. And, after a slow start, it was the European Commission, the EU's executive body, which organised many of the continent-wide aid efforts.

Nonetheless, it is a fact that, when the chips were down, when a terrible crisis faced their continent, ordinary Europeans turned to their own national governments for guidance and protection, and not to EU institutions. And it is also a fact that the governments' first reaction was to close borders and hoard medical supplies.

Yes, there were moving, noble gestures, such as Germany's decision to airlift gravely ill Italian and French patients for medical treatment in German hospitals. Still, the EU's claim to act as a continental shield and a force multiplier for its nation states has been exposed as hollow.

The health emergency was the EU's opportunity to make its mark; as the old political saying goes, "never waste a good crisis".

But as far as the EU's reputation is concerned, this was a crisis wasted. And the results are already there: Current opinion polls indicate that around 40 per cent of Italians want their country to leave the EU.

THE GERMAN COURT'S CHALLENGE

More significantly still, the crisis has the potential to open further and graver European divisions.

The only way countries such as France, Spain or Italy can finance the huge debts they are incurring as a result of handling the pandemic is if the treaty provisions governing the operation of the euro common currency are suspended for a number of years.

But even if one assumes that this is possible, a recent decision by Germany's constitutional court means that in less than three months from now, the Bundesbank, Germany's own national bank, will be forbidden from participating in the purchase of the debt of other EU states unless the European Central Bank is able to explain how such purchases of debt are in accord with existing EU treaties.

Without German contributions, there are unlikely to be other purchases of debt and, without that, some EU states may face national bankruptcy.

Almost every European politician and institution has pounced on Germany's constitutional court, dismissing its decision as legal nonsense and claiming that it has no jurisdiction over European institutions.

But much of this criticism is misplaced, for all the German court has done is to rule that the behaviour of European financial institutions is not in accordance with the provisions of the German Constitution, or with the powers which Germany has transferred to European institutions - two matters which, surely, Germany's top court is empowered to decide on.

And if one does not agree with this interpretation, the fact remains that, unless the European Central Bank finds a plausible explanation for what it is doing in support of the borrowing requirements of individual states, the German government will be faced in a few months from now with the unenviable choice of either ignoring the ruling of its own court, or pulling the plug on one of the key European financial mechanisms.

In effect, Germany's top judges have exposed the EU's two existential flaws: that the euro cannot continue to operate a common currency of states which have their own budgets and taxation systems, and that the current debts which EU countries are assuming cannot be serviced at affordable rates unless the Germans - as Europe's paymasters - are prepared to take them on as joint liabilities.

In short, Europe's existing currency union must become a transfer union, a union in which German wealth is used to alleviate poverty elsewhere, and for decades to come. Good luck to the German politicians who succeed in persuading their voters to accept such an open-ended liability. But without such an undertaking, it is hard to see how the current union can hold together. A health crisis about to morph into a financial crisis could be just as virulent.

The coronavirus has also upended Europe's ability and perhaps also its aspirations to be an international actor. The continent will continue to uphold the principles of free trade and multilateralism; after all, the EU is still the world's largest economy and largest trading bloc. It is also the world's largest trader of manufactured goods and services and ranks first in both inbound and outbound international investments.

But the health crisis will strengthen the forces of deglobalisation in Europe and will result in the "reshoring" of production and supply chains, especially in what are deemed to be strategic commodities and goods, such as medicine and medical equipment, but also certain leading technologies.

THE CHINA CHALLENGE

Europeans may still nurture hopes of adopting a critical but friendly policy towards China. Nonetheless, the pandemic has shattered European dreams about their relationship with China, and that will have profound consequences.

For decades, China was seen as just a big business opportunity. Unlike Russia, viewed in Europe as a rival that wants to overturn European security structures, China was always regarded as a broadly benign partner. Indeed, that was so embedded in European psyche that many Asian and American leaders used to berate Europe for its naive approach.

That too has changed. China's recent diplomatic assertiveness, which often disparaged the performance of European governments in managing the health crisis and seemed to encourage EU internal divisions, has resulted in a fundamental change in European perspectives.

When official Chinese media outlets poke fun at Europe or threaten to cut off medical supplies unless European governments stop criticising China, it is not surprising that European governments are forced to rethink their old premises.

Few European leaders are talking about "decoupling" their continent from Chinese trade. But "diversifying" trade links is very much on European minds. And countries in central and eastern Europe are readying themselves to become the new favourite destinations should other Western multinational corporations seek to diversify their production lines away from China.

CHANCE FOR RENEWED STRENGTH

The result is a continent that is both more vulnerable, more apprehensive about its future and more suspicious of the world outside; the benign global environment which the Europeans expected is not about to be realised.

But it is also a continent that can transform temporary weakness into renewed strength by becoming more willing to strike global alliances with potential partners and participate in global efforts to contain potential rivals.

This is something that may well result in a new European bargain with the US after that country's presidential election is out of the way. At least from this narrow perspective, the coronavirus pandemic has been well timed.