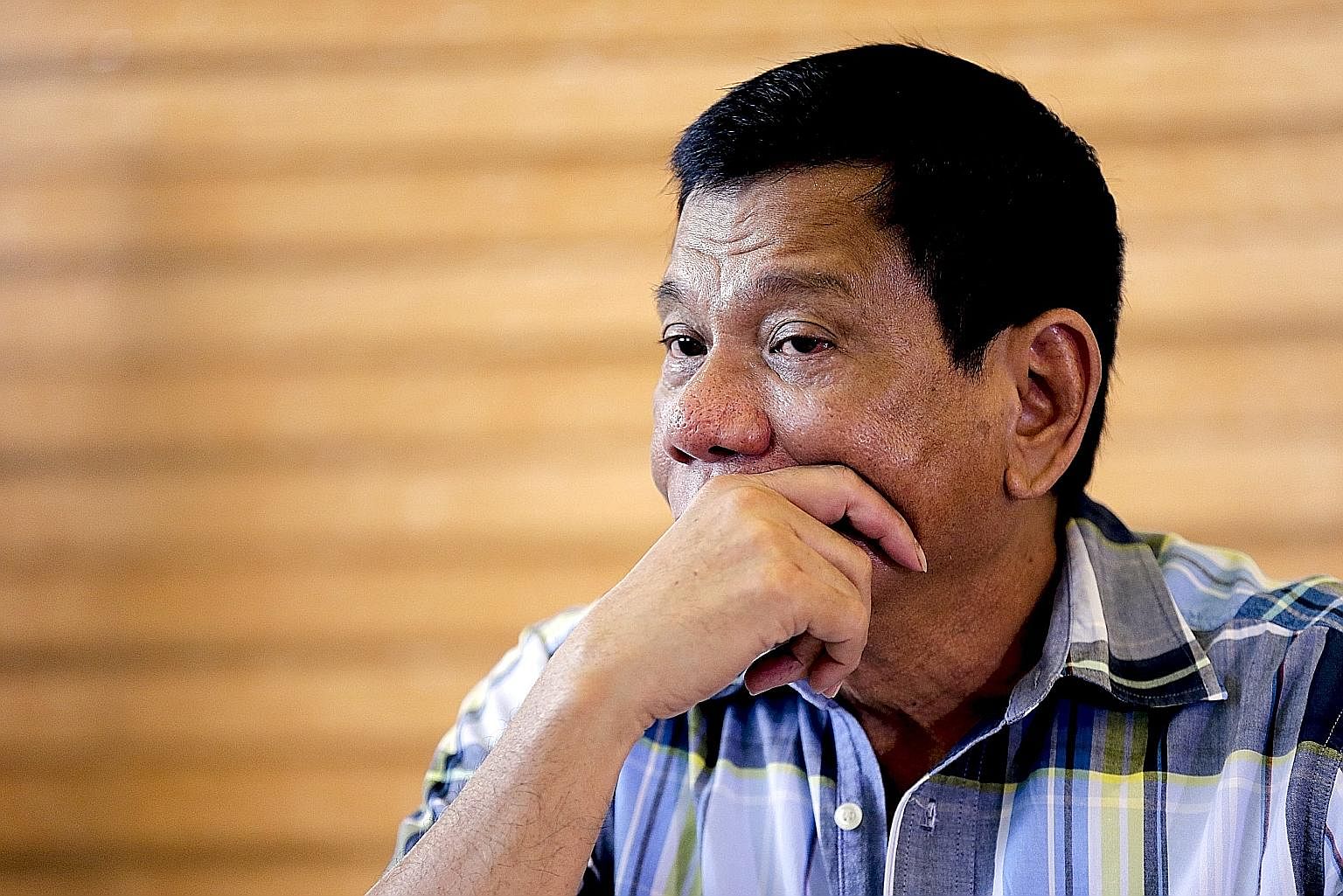

Richard Javad Heydarian After months of gruelling election campaigning, which saw unprecedented mudslinging among leading candidates, the Philippines pulled off one of its most peaceful and credible presidential elections in history. Only a few hours after the closing of polling stations, it became crystal clear that Mr Rodrigo Duterte, the firebrand mayor of Davao City, was the leading choice of a large plurality (38.5 per cent) of voters.

The provincial mayor edged out his closest rival, seasoned technocrat Manuel "Mar" Roxas, by more than five million votes. The following day, Mr Roxas made an affable concession speech, extending an olive branch by wishing his opponent success. Taking notice of the overall smooth process of democratic transition, the Philippine Stock Exchange hit a nine-month high after months of nail-biting anticipation.

Mr Duterte's fiercest critics, including Senator Antonio Trillanes and key sectors of the civil society, also offered their (conditional) support to the newly-elected president. Major political parties have also begun to bandwagon behind the new leader.

Though broadly known as a "loose cannon" with a penchant for off-the-cuff comments, Mr Duterte, however, will most likely adopt a more pragmatic and constructive policy towards China and the South China Sea disputes. He is expected to adopt an equilateral balancing strategy vis-a-vis Washington and Beijing, cooperating with each superpower, depending on the issue at hand.

In recent days, Mr Duterte, who gained international notoriety for his highly controversial comments in recent months, has promised to become more statesmanlike, shun profanity and provocative language, and assemble a highly competent and inclusive presidential Cabinet.

Reports suggest that his presidential Cabinet is likely to field technocrats and stalwarts from the Ramos (1992-1998) and Arroyo (2001-2010) administrations. With the Philippines slated to assume the chairmanship of the Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean) next year, Mr Duterte has less than a year to transition from a campaign-trail brawler into a predictable and dignified head of state.

In contrast to the Western media coverage, he is no Donald Trump. He boasts more than two decades of actual executive experience. He is broadly credited for transforming, albeit with an iron fist, the southern city of Davao from a Hobbesian arena into a relatively safe and prosperous refuge in the conflict-ridden island of Mindanao. Until recently, Mr Duterte was a political outsider par excellence. At one point, he almost considered withdrawing from the presidential race altogether, but he was encouraged by the weakness of his more mainstream opponents and a growing climate of "grievance politics" among voters.

Vice-President Jejomar Binay, who was a stellar mayor of Makati City, the country's financial hub, struggled with corruption scandals, which alienated many voters. As for Mr Roxas, the anointed successor of incumbent President Benigno Aquino, he ended up as a referendum vote amid a growing public outcry over the lack of inclusive development and collapsing public infrastructure in the country, especially in the vote-rich national capital region.

Meanwhile, neophyte Senator Grace Poe, a former American citizen and a perennial leader in surveys, struggled with legal challenges over her eligibility. She also alienated many middle-class voters by associating with reviled oligarchs and establishment politicians. Leveraging a sleek electoral campaign, which often bordered on fear-mongering, Mr Duterte managed to astutely portray, especially towards the end of the race, his opponents as either corrupt, incompetent or puppets of the ruling oligarchy.

Meanwhile, he presented himself as an "authentic", independent candidate with the requisite political will to address law-and-order concerns in the country. He also promised more political autonomy and fiscal resources to peripheral regions. Apparently, this strategy was sufficient to garner him the largest share of the votes.

Despite some of his Trump-like blusters, namely his intention to drive a jet ski to and plant a flag on disputed islands, Mr Duterte has consistently expressed his willingness to have direct dialogue with the Chinese leadership, negotiate a joint development agreement on contested waters, and welcome massive Chinese investments in the Philippines' infrastructure landscape.

For him, when it comes to China, development trumps deterrence and confrontation. In one of his speeches, the incoming president went so far as telling China to "just build (the Philippines) a train around Mindanao, build me a train from Manila to Bicol… build me a train (going to) Batangas. For the six years that I'll be president, I'll shut up (about sovereignty disputes)."

He has even shed doubt on the utility of the Philippines' arbitration case against China, raising the possibility that he may simply snub (a likely favourable) verdict as an advisory opinion in order to re-open high-level communication channels with China and negotiate a modus vivendi on disputed waters. In response, Beijing has openly expressed its interest in rebuilding frayed bilateral ties under a new administration.

Despite his well-known association with leftist-communist groups, and his efforts to reach out to China, Mr Duterte can't afford to alienate Washington, which enjoys high favourability among the Philippine security establishment. So he will most likely maintain robust security relations with America, particularly in the realm of counter-terrorism.

Lamenting America's minimal assistance to the Philippines, and the Obama administration's equivocations on the extent of its defence treaty obligations to the country, Mr Duterte, however, is expected to drive a harder bargain before granting Americans more basing access under the Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA).

In short, the Duterte administration will try to strike a balance between its relations with major powers, gradually distancing itself from the Aquino administration's more confrontational approach to Beijing over the South China Sea disputes. The foul-mouthed provincial mayor may, after all, end up as a more skilled player in regional geopolitics.

•The writer is a political science professor at De La Salle University in the Philippines.

•S.E.A. View is a weekly column on South-east Asian affairs.