LONDON • For the moment, all European governments are concentrating their entire firepower on fighting the still virulent coronavirus epidemic.

But behind the scenes, a battle just as critical to the future of the continent is unfolding, about the ways European states should manage the huge economic costs of the pandemic.

There are no easy solutions, for the damage to European economies will be massive and long-lasting; the real choice facing Europe is whether these should be borne by all countries together, or by each one individually.

And while nobody should doubt the sense of solidarity that binds European governments, the Europeans have a history of stumbling on the solution only after exhausting all the wrong options.

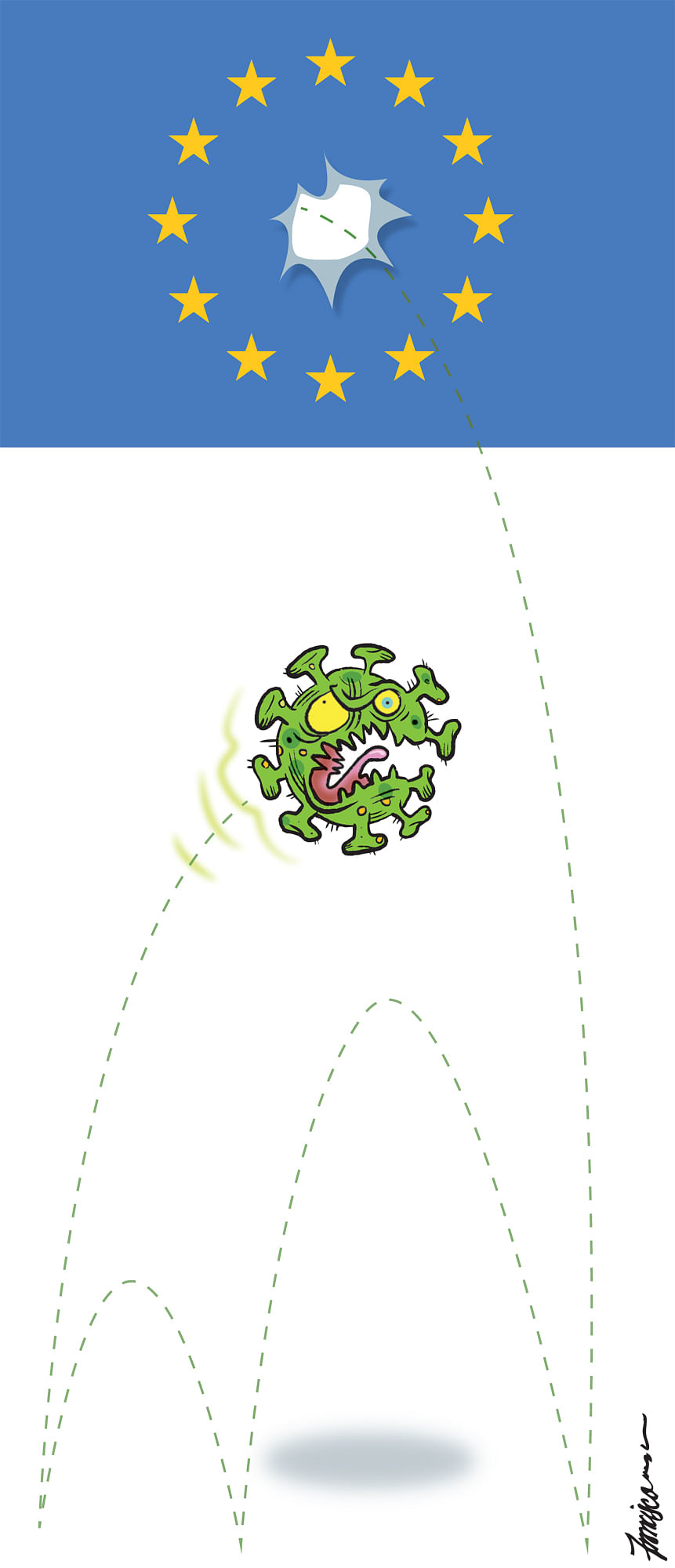

Either way, nobody doubts what is at stake here: the very survival of the euro and, perhaps, of the European Union (EU) itself. The coronavirus is confronting Europe with a challenge just as existential and as grave as that of a war.

Estimates of the pandemic's potential costs to European economies are impossible to compute with any degree of accuracy at this stage, since there are so many variables. Nobody knows how long the crisis will last and how many weeks or months key European states will have to remain in lockdown.

Nor can Europe escape the ripple effects of economic downturns in China and other parts of Asia, as well as in North America. So it is not a surprise that even those brave economists and analysts who are willing to hazard a prediction are unable to reach a consensus; some predict a "V-shaped" recovery with a sharp rebound after the current steep decline, while others assume a longer "U-shaped" recovery.

Although each scenario implies different policy choices, certain major conclusions are emerging clearly enough.

The first is that the initial batch of national statistics from individual EU member-states indicates that the economic impact of this crisis will be huge. Over the past few days, for instance, the French statistical agency revealed that France's economic output is already down by 35 per cent and that the crisis this year will knock three points off French gross domestic product (GDP) if the lockdown lasts a month, and 6 per cent should it last two months.

If projected to all the countries in the euro zone, most estimates now assume a contraction of 15 per cent of GDP in the second quarter of this year and around 10 per cent for the whole of 2020 - figures that are comparable to those recorded during the darkest days of the Great Depression in the 1930s, and about 10 times worse than the economic contraction experienced during the 2007-2008 financial crisis.

Furthermore, governments throughout Europe are now pledged not only to cover the salaries of people retrenched as a result of the economic downturn, but also to pouring money into national enterprises in order to save them from collapse, and underwrite the biggest single expansion in state spending on healthcare since World War II.

The age of big government is back with a vengeance as countries return to the ideas - dominant 50 years ago - that governments and not the private sector are the best managers of economies and the best allocators of resources. And this applies to European countries ruled by centre-right politicians, as much as it does to countries where state spending was always high.

Take for instance the British government, elected only last December on an agenda strongly in favour of private enterprise; it has just made spending promises equivalent to about a fifth of the national economy, a staggering amount unprecedented in the country's peacetime history.

And what is one to make of Germany, a nation so ideologically averse to borrowing that it has made the so-called "schwarze Null" (black zero) - a commitment to zero deficit in national budgets - a binding legal requirement on all its future governments?

All this caution was thrown to the wind in the past few weeks, with offers of around €600 billion (S$953 billion) of state credits which are not only designed to protect ordinary Germans from temporary hardship, but also to buy government stakes in German firms which may be subject to hostile takeovers. One candidate for such a "nationalisation" may well be Lufthansa, the German airline which has practically halted its business. If this happens, it will signify a complete and fundamental reversal of decades of economic liberalisation policies in Europe.

The snag is that while each European state's effort to rescue its national economy can be justified as a response to an extraordinary emergency, the cumulative effect of all these national initiatives is to tear to pieces the EU's current financial arrangements.

The European Stability and Growth Pact, which governs the operation of the euro, requires member states to keep their budget deficits at not more than 3 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). It also requires states' national debt to go no higher than 60 per cent of GDP. Italy and France, to name but a few, were already at 130 per cent and 100 per cent respectively in terms of national debt even before the epidemic. And with the full lockdowns, those figures will soar.

If all the German promises to lend to its economy are cashed in, Germany itself may register a budget deficit of around 5 per cent of GDP - almost double the rate demanded by European treaties - and could see its total national debt soar to around 80 per cent of GDP.

So, while in previous EU financial crises Germany acted as the policeman ordering all other nations to respect their obligations, this time the Germans are also "sinners". Besides, the EU has already bowed to the inevitable by lifting its budget caps, for the first time ever.

But this is a temporary, exceptional measure. And as the most indebted countries in Europe know too well, ultimately they can only afford to borrow the sort of money they are currently pledged to spend if Germany and the rest of the euro zone are able to guarantee this borrowing. Without this mutual guarantee, repaying the interest and capital on this sort of debt will become unsustainable, just as it was for Greece, which faced bankruptcy a decade ago.

Italy already cannot issue a guarantee to bail out its private firms as France is offering because Italy's debt ratios are already regarded unsustainable. And as the downturn grips, other EU countries risk being sucked into the same predicament.

One option may be to use the European Stability Mechanism, a fund worth €400 billion created in the wake of the last financial crisis, in order to support the current borrowing needs of nations. Another relief could come from the €750 billion fund which the European Central Bank has pledged to spend buying the bonds of euro zone member-states.

But access to all these funds comes with conditions which will ultimately force the borrowing countries to accept the sort of gut-wrenching horrible economic austerity conditions Greece suffered, only to still remain one of Europe's most-indebted nations.

That is why last week the leaders of France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Belgium and Greece demanded the creation of a "common debt instrument" which, on the suggestion of the Italian prime minister, ended up being nicknamed the "corona bonds".

The idea is that these badly-named bonds will be guaranteed by all EU member-states, carry no political conditions and, as leaders of the demanding countries politely put it, should be of a "sufficient size and maturity" not to threaten Europe's future economic recovery. Translated into normal language, what these countries are asking for is a great deal of money with no questions asked and no need for repayment for some decades to come.

Unsurprisingly, the Germans who are going to have to foot the bill for these bonds will not hear of it. At a "virtual" EU teleconference summit last Friday, German Chancellor Angela Merkel simply repeated her "nein" response no less than four times. Her refusal was echoed by the Dutch, whose Prime Minister Mark Rutte said he "cannot foresee any circumstances in which the Netherlands will accept euro bonds".

EU leaders hope to ultimately wear the German and Dutch opposition down, as the sheer scale of Europe's problems becomes clear. But that would be a feat of monumental proportions. Without a constitutional change, the German government simply has no powers to accept such liabilities. Nor is there any political consensus inside Germany to shoulder such continent-wide obligation. German politicians fear - not unreasonably - that once the principle of guaranteeing other countries' debt is accepted, there will be no end to further requests of the same nature.

And most German officials believe that the other Europeans find themselves in such a predicament now because they failed to reduce their outstanding debts over the past few years, when their economies were growing.

More significantly, the timing for accepting such a fundamental obligation could not have been worse for the Germans, just as Germany itself is about to experience an economic downturn, just when Germany's own borrowing requirements are likely to balloon and just when Chancellor Merkel is facing retirement after more than 15 years in office. A least favourable sequence of events could have hardly been invented.

But without this German guarantee and without the creation of bonds mutually guaranteed by all, it is difficult to see how the euro could survive the pressures between the needs of its poorer south, and the reluctance of its richer north to pay for it.

The continent faced exactly the same challenge a decade ago, and ducked the question by bailing out Greece from bankruptcy, while passing on the horrendous costs of that operation on to the Greeks themselves.

Yet with hindsight, that was just a mere rehearsal for what is about to unfold now, involving far bigger economies such as Italy or France. Without a mutual debt guarantee which prevents another debt crisis, the entire euro edifice may collapse.

Nobody should underestimate Germany's determination to save the euro, or the EU's determination to stick together in moments of crises; those who betted in the past on the euro's demise were wrong.

Still, the stakes are huge, and the dangers bigger still. None other than Mr Jacques Delors, the former French politician and the man who shaped the EU of today, now warns that "the climate which seems to reign between the heads of states and governments and the lack of European solidarity pose a mortal danger to the European Union".

"The microbe is back", he adds. And he is not referring to the coronavirus.