Covid-19 is upending the traditional doctor-patient relationship in many ways.

The latest, and perhaps most consequential, change is taking place right now, in thousands of homes and clinics across Singapore, and millions more around the world.

As hospitals face bed shortages, people infected with Covid-19 are asked to stay home and monitor their own health. While patients through the ages have sought to recover at home before seeking medical help, especially if they live far from a hospital, during this Covid-19 pandemic, Singapore is trying to scaffold its home recovery programme with sufficient assistance to help patients help themselves.

Patients are expected to take their temperature, check their pulse and blood oxygen saturation level, and know when, how and who to get help from when their symptoms worsen.

In Singapore, a multi-tier system of support has been cobbled together, with online resources, a care pack, a home recovery tele-buddy system, and a network of clinics with doctors on standby, and ambulance services on call.

A year ago, such a move to get patients with Covid-19 to recover at home would have caused panic. Today, it is the norm, as those diagnosed with Covid-19 number in the thousands each day.

Thousands of people are recovering from Covid-19 at home, while trying not to infect family members. For example, they are advised to stay in a separate room and have family members bring them meals and dispose of their trash; and to wash their clothes separately from the rest of the household. Bathrooms are to be wiped down frequently.

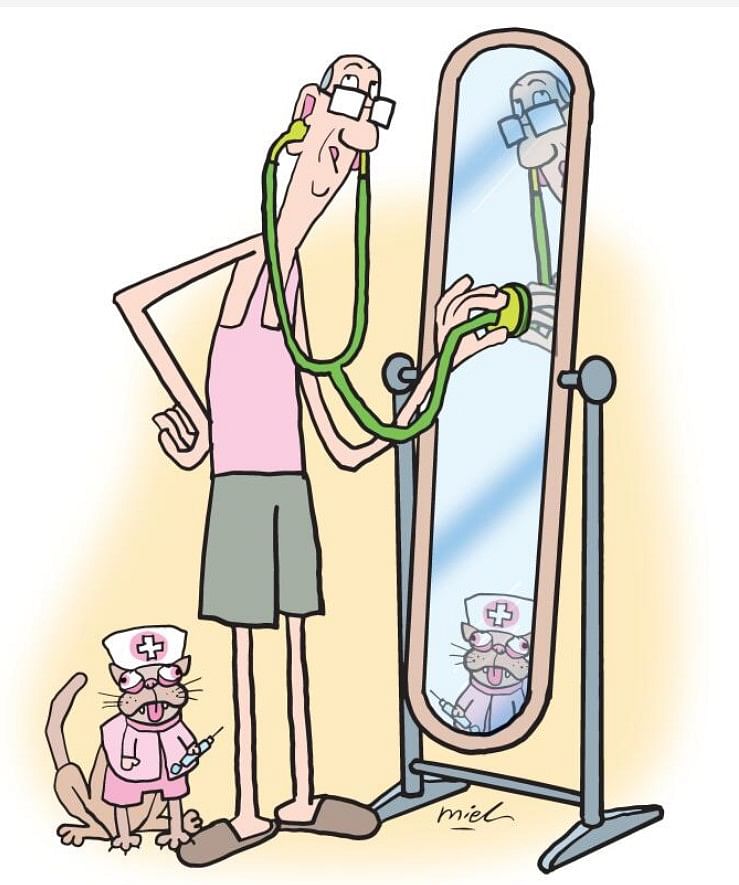

The shift to home recovery as the default for Covid-19 infection empowers patients to be their own healthcare provider. It overturns the traditional doctor-patient relationship where the doctor knows best and the patient complies with instructions.

It puts patients in charge of their own care, with medical professionals as resources to be tapped when necessary. This shift to patient-driven care is one visible example of how the global pandemic is overturning the caregiver relationship here.

If harnessed well, the potential energy from activating patients' sense of self-responsibility can be used to help the doctor-patient relationship mature from an unequal one now, to one based on a greater sense of partnership.

An unequal relationship

The traditional doctor-patient relationship is based on inequality. On one side, a credentialed doctor in officious white coat in his office, standing or sitting vertical; on the other side, a patient feeling sick, anxious, often lying horizontal in a state of undress, to be examined, tapped, prodded. The asymmetries of posture, information and bodily boundaries create an immediate power dynamic which puts the doctor in the dominant position.

Good medical training does its best to inculcate empathy and compassion in doctors, but it is by no means given that a doctor who graduates from medical school will be able to view his or her patients with anything other than condescension or tolerance.

The imbalance in relationship is most clearly demonstrated in the long waiting times to see doctors - no matter if the patient is a chief executive, the minute he becomes a patient, his time is worth less than that of the most junior doctor.

The privatisation of healthcare has created a slightly different dynamic, of viewing patients as customers whose fees pay for doctors' quality of life. This can be positive when it means doctors and healthcare institutions are forced to respect patients' time and generate efficient workflows to reduce inconvenience to patients.

Some hospitals design their work processes to be patient-centred: for example, locating speciality clinics for common conditions to minimise walking time for patients within a hospital complex. A diabetes centre for example might have a foot clinic and eye clinic in it, as patients with diabetes often suffer complications in these areas.

In the well-regarded Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston in the United States, I felt cared for by my medical team that included a cancer surgeon, a medical oncologist, a nurse practitioner, a physiotherapist, a chemotherapy nurse and even a chaplain to attend to psycho-spiritual needs. At the centre, appointments are organised around the patient: I wait in a room and the requisite doctor comes to see me. People may say that the US system is able to do this for overseas fee-paying patients - but I was just a foreign student funded by university health insurance. This was nearly 20 years ago, when patient-centric care was not the buzzword it is today.

In Singapore, too many of our public hospitals and clinics, even in non-pandemic times, are bursting at the seams with too many patients, conditioning many Singaporeans to wait times of one to two hours, to see a doctor for a few minutes.

Many public healthcare systems are organised around a scarcity mindset based on the assumption of unequal value of time: too few doctors with too little time, and too many patients with too many ailments needing attention. The public-funded National Health Service in Britain suffers from similar, or worse, wait times for treatment.

Over-stretched healthcare systems cause fatigue in medical professionals who make mistakes that can cost lives. Patients taxed by long wait times get irascible. The result is some conflict in doctor-patient relations.

The pandemic, however, is changing this dynamic.

Shift to preventive care

As infection numbers grow and hospitals' occupancy swells, citizens can see clearly just how overworked their healthcare workers are.

More citizens also understand the relationship between their personal state of health and the healthcare system. We see with greater clarity how our own habits and behaviour can result in the infectious disease spreading faster to more people, so that more people get very sick, and there is more demand on doctors, hospital beds and acute care resources such as oxygen and intensive care unit beds.

The link between citizens' private behaviour, and the pressure on public healthcare resources and hence the cost of healthcare, is being made more visible.

Living through this pandemic is a good way for us to understand the importance of preventive measures. Social distancing and mask wearing are preventive measures all of us undertake daily, to protect ourselves from the virus that causes Covid-19.

The message that small, daily, individual steps can prevent a major disease outbreak, or reduce the chance of severe illness, is one that we should remember. Preventive care in peacetime could mean taking better care of our diet and lifestyle, cutting out unhealthy habits like smoking, and, yes, donning a mask when one gets the sniffles, to protect others.

Healthcare needs will change, when more people understand the link between their individual health habits and the healthcare system, and take personal responsibility for their health. Instead of so many resources devoted to acute hospital care, more resources can be allocated into upstream, preventive measures such as building more neighbourhood parks and park connectors. Mr Liak Teng Lit, former CEO of several different hospitals, says he used to tell government ministers to reduce hospital budgets and give more to the National Parks Board.

Public sympathy, tolerance of mistakes?

The pandemic is also changing the way the public views healthcare workers.

They are universally hailed as heroes across the world, as they work long hours, putting themselves at risk, donning uncomfortable protective wear, to tend to large volumes of sick people who are infectious. Many initiatives have arisen to show them appreciation: from a worldwide movement to clap for healthcare workers to the ongoing Straits Times campaign to encourage readers to share #STcovidheroes posts on Instagram.

With public sympathy rising for beleaguered healthcare workers, will this translate into greater understanding of how care can be compromised in the face of resource constraints?

Dr Pallavi Bradshaw, medicolegal lead, risk prevention, at the British-based Medical Protection Society (MPS), wrote in a blog in June last year on The BMJ website: "I wonder whether the respect and empathy being shown by the public, and press, towards healthcare workers will translate to greater tolerance of medical error. Can we now accept that stretched staff and resources will not always deliver high quality care and that, on occasion patients may be harmed?

"MPS has called for emergency laws to protect UK healthcare workers from criminal and regulatory investigation - a call supported by two-thirds of the public, according to a YouGov survey of over 2,000 adults in Britain."

There is also a fear of claims arising from misdiagnosis, or delayed treatments from non-Covid-19 cases, as resources are diverted to deal with the pandemic.

In the United Kingdom and United States, which are societies with active liability markets and high Covid-19 mortality rates, there is public discussion on indemnity for healthcare professionals. Options include giving indemnity to healthcare professionals for Covid-19 and related care so long as they act in good faith; or satisfy a reasonableness test; or are not grossly negligent.

In Singapore, there has been no noticeable public chatter on this issue, but this does not mean the issue will not arise.

Covid-19 has both shown the public how heroic healthcare workers are, and also how fragile they are, as many succumb to the disease they are treating patients for. As the disease spreads through the community, especially before vaccination removed its deadly fangs, the public saw how helpless doctors were to stem its spread, and how futile many treatments were. Reports were rife too of healthcare systems that collapsed under the sheer weight of patient numbers, with patients dying in hospitals, outside hospitals, dying while waiting for a hospital bed or dying at home, having given up the rush to get to overcrowded hospitals.

Monitor own health

In Singapore, the home recovery programme was designed precisely to avoid that situation of overwhelmed hospitals.

A regime of self-testing is also being encouraged, so members of the public who are infected but asymptomatic can self-isolate and reduce the chance of spreading the disease to family and friends, and inadvertently sparking a cluster.

As the Ministry of Health (MOH) notes: "As Singapore gradually transits to being a Covid-19 resilient nation, society will play an increasingly important role to manage the pandemic."

Memes going round already joke that MOH now stands for Monitor Own Health.

While it might have been intended as a dig at MOH for moving patients to home recovery, in fact the notion of patients monitoring their own health is a good one to carry into our personal lives post-Covid-19.

When patients step up to take responsibility for their own health, to learn about their disease and symptoms and know when to escalate to seek help; when they work on preventive measures; and when they learn to accept that medical professionals have flaws and make mistakes - those will be some signs of a maturing patient-doctor relationship.