As the American Century makes way for a China-led Asian Century, the likely advent of a new global order is raising anticipation as well as apprehension.

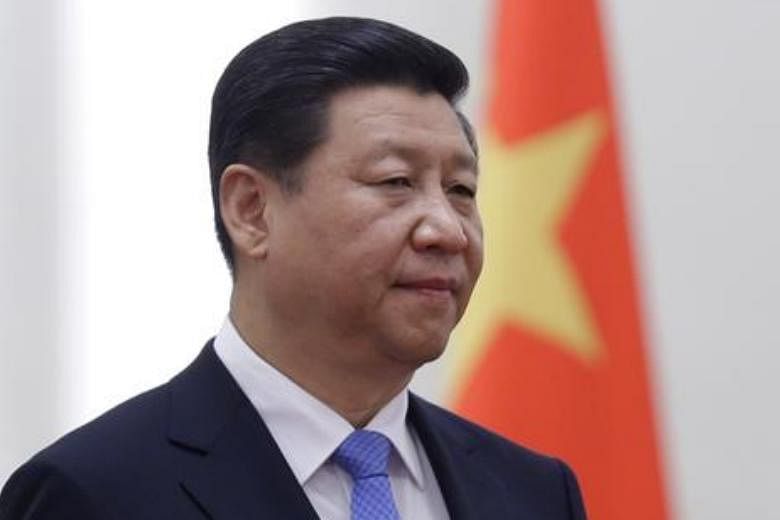

Curiously but not surprisingly, the role of Confucianism has attracted the attention of many. Once condemned as feudal by China's communist rulers, this ancient tradition is experiencing a renaissance of sorts, engineered by Chinese President Xi Jinping no less.

Already, some cynics see in this rejuvenation an usurpation of Confucian idealism by Marxist pragmatism. In the longer term, however, most foresee the eventual return of China to its ideological roots. And when a rising, and increasingly assertive, People's Republic of China becomes re-Confucianised, will this also portend a Confucianisation of the world?

A look back into the past exploits of two maritime heroes could provide us with some insights into this unfolding future. In 1405, Zheng He began traversing the Nanyang with multiple stopovers in Malacca, eventually reaching the Horn of Africa. Nearly a century later in 1498, Vasco da Gama navigated the Cape of Hope, docked in Malacca, before dropping anchor in Macau.

These epoch-making voyages may be seen as the historical epiphanies of the Sinic-Confucian and Euro-Christian global aspirations respectively. Indeed, Christianity calls on its members to spread the Gospel to all of mankind. The sanguine Confucians are similar in the breadth of their worldview - that of the human potential to attain civility.

The Portuguese and other European explorations subsequently covered the four seas, colonising and Christianising the New World. While controversial, it propelled Christianity into a truly global religion, as church spires now pierce the skies of every continent.

The Ming seaborne expeditions, by contrast, were short-lived and geographically confined to maritime Asia; imperial power was imposed indirectly via the tributary system. Most markedly, there was no Confucianisation of the minor kingdoms. Instead some credited Zheng He, a Hui Muslim, for being a catalyst in the Islamisation of the Malay archipelago.

Ergo, after over two millennia, this ancient Chinese philosophy remains a regional (north-east Asia) phenomenon and parochial (Han-centric) tradition.

Why is it that Confucianism - a philosophy as groundbreaking as any that came out of the Axial Age - did not display the same zeal as Christianity to convert the world?

The answer lies in the varied ways their respective moral visions were pursued.

To be a Christian, one must abide by two norms: the natural law, revealed to all, plus another set of divine law revealed to Abraham and his descendants.

Christians believe the Bible is the final depository of these decrees. Furthermore, they see it as their mission to spread the message of salvation, seeing it as a sacred duty of being God's "chosen people". This sense of exceptionalism has driven the West's efforts to Christianise the world. It also underpins America's sense of "manifest destiny" and its vision of being that "shining city on the hill" tasked with providing global moral-political leadership.

In Confucianism, to become civil requires one to live by the moral laws already revealed in nature.

There is no equivalent notion of Heaven communicating exclusively to specific peoples. Every person, and by extension every human tradition, has access to the principles needed to actualise a cultured existence.

The multiple-religiosities practised by the Chinese epitomises this inclusiveness, whereby a person could claim to be a Confucianist, a Taoist and Buddhist, all at once. This syncretic co-existence underscores the Confucian belief in there being "many ways" to realise the ideal.

Put differently, Confucianism disavows any monopoly of truth. Moral pre-eminence is not predestined but merit-based. Even Confucianism itself is not spared.

The history of modern China is instructive: stricken by internal decay, Confucianism, the erstwhile moral foundation of the Sinic civilisation, was found wanting and cast unceremoniously aside from the mainland, which turned instead to Mao and Marx for guidance.

Fast forward to the present, the China of President Xi.

It is now a political and economic powerhouse but still searching for better ways to extend its influence and raise its profile. Mr Xi's signature Belt and Road Initiative is one vehicle to engage its neighbours economically and politically, and its historic Silk Road references dovetail neatly with the romance of Zheng He's voyages.

But on the soft power front, "socialism with Chinese characteristics" is a hard sell.

And here's where Confucius makes a comeback. Confucianism is truly native and its ancient roots make it another great vehicle - this time for Mr Xi's goal of promoting Chinese civilisation and culture. Money was pumped in to establish a global network of Confucius Institutes.

It is not without controversy, not least as sceptics doubt if these are bona-fide conduits of Confucianist precepts. Others warn of Trojan horses implanted in foreign universities to propagate illiberal ideologies. Be that as it may, when Confucianism becomes fully rejuvenated, will China seek to "Confucianise" the world?

If history is a reliable guide, the answer is no. And the reason is because there were no mandates to do so.

Certainly, some civilising impulses remain but the sweeping infusion of our emerging new world order with "Confucian characteristics" is unlikely.

In the ethical universe envisioned by the ancient Chinese sage, moral leadership is not the sole prerogative of any, but the duty of many.

A revitalised Confucianism could well play a prominent role, but merely as one among equals, together with other worthy faiths and worldviews to advance the fate of humanity.

•The writer is a senior lecturer at the Institute of China Studies, University of Malaya.