China's economy is fragile. But it is not on the verge of collapse. It has the resources to avoid a hard landing. But execution of reform remains weak and piecemeal. The top leadership know what the problems are. But these problems - high leverage, excess capacity and an inefficient state-enterprise sector - are huge, complex and do not take place in a vacuum. Politics dominates.

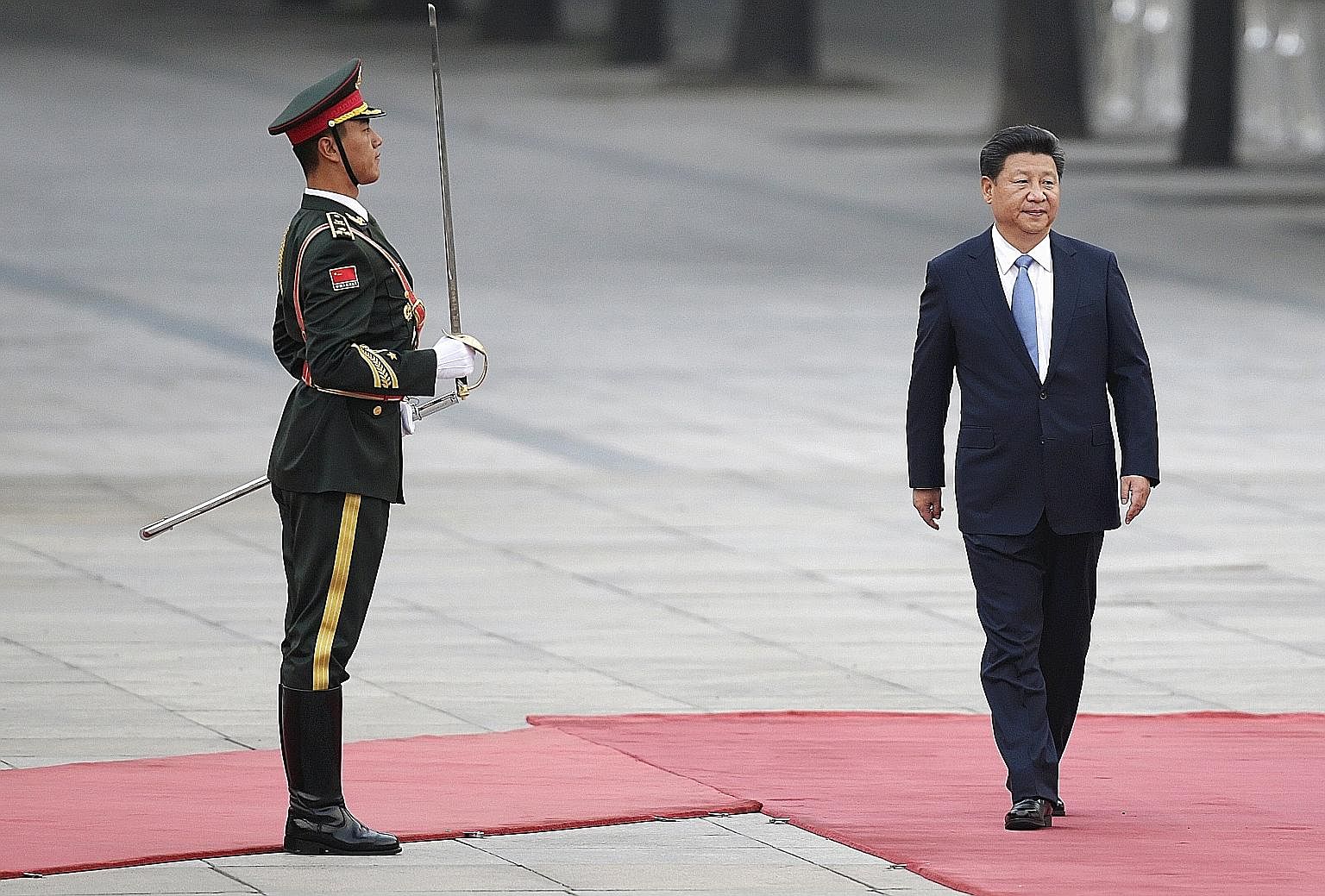

Politics is both the problem and solution. Politics is a big problem as there are strong vested interests resisting reforms. This is why China's leader, Mr Xi Jinping, had to rapidly consolidate and centralise his power since ascending the summit of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as General Secretary. The enormity of his reform agenda cannot be overstated as the party is, in effect, taking on itself. As Mr Xi said: "China's reform has entered a deep-water zone, where problems crying to be solved are all difficult ones. We must get ready to go into the mountain, being fully aware that there may be tigers to encounter."

But Mr Xi's top reform priority from the start was not economics as many had expected, given the slowing economy and structural headwinds, but politics. It was first and foremost to strengthen the CCP. As far as he is concerned, unless you get the politics right, meaningful economic reforms will be very difficult to achieve and sustain. The robust anti-corruption campaign that was unleashed was part purge, part cleansing. Yes, rivals were taken out but its wide extent and longevity underline the resolve to purify and discipline the CCP. This is because of widespread public disaffection with the corruption and abuse that had seriously infected the party, government and military in the preceding "go-go" years.

Mr Xi believes that only the CCP can ensure the stability that is necessary for China's future. Thus his aim is to restore its moral authority to continue to lead and govern China. As a veteran China-watcher told me: "Chinese dynasties collapse, not when they are taking on corruption, but when they are not."

MORE POWER CONSOLIDATION TO COME

Power consolidation will take another decisive turn next year. Unlike an American president, Mr Xi did not get to choose his senior leadership team when he first became China's leader. Members of the party's apex decision-making body, the Politburo Standing Committee, were foisted on him by competing factional interests.

At next year's party congress, the majority would retire, thus giving him the opportunity to influence its composition to be more aligned with his interests and agenda.

Presumably, once he has further consolidated his power, there will be greater appetite to undertake difficult reforms. But those who hope for a sharp pickup in the pace of economic reforms are likely to be disappointed.

Even with the best of will, China's huge and complex economy means that effecting reforms will be a multi-year effort. The fact, however, is that there is no "best of will" to implement the reforms. The anti-corruption campaign has made officials hesitant to take action as they never know when they will be accused of "serious disciplinary violations", even in retirement. This lack of transparency on the party's internal investigation process has made risk-aversion the default position of many.

Compounding this problem is that even for officials who are inclined to act, there is confusion as to exactly who is in charge of economic decision-making and which decisions to follow. The confusion stems from the blurring of the line between the party and the government in the economic management of the country.

Under Mr Xi, the party's "leading small groups" in "deepening reform" and "finance and economics", which are headed by him, have moved from oversight to being actively involved in economic matters, thereby undermining the traditional authority of the State Council led by the Premier. Consequently, the policymaking process is muddy and lines of responsibilities are fuzzy.

XI THE ARCHER

But perhaps the biggest uncertainty is Mr Xi himself. He is a political conservative as seen by his distinct leftward lurch in politics since he came into power. As he puts it, China's economic reforms need to make "good use of both the invisible and visible hand". The desire for political control sits uneasily with economic reforms that profess to build on Deng Xiaoping's "reform and opening" policies. This tension between political conservatism and economic liberalism has manifested itself in the increasing politicisation of economic decision-making as officials are told to "take reference from the centre".

In turn, this has affected the direction and efficacy of policies and brought into question the competency of China's leaders in managing the transition from Mao Zedong to markets. The spectacular boom, bust and massive missteps in trying to shore up the Chinese stock market last year is a case in point. Politics ruled the roost here. The boom was fuelled by irresponsible official encouragement as a painless way to deal with the problem of highly indebted state-owned enterprises and as part of Mr Xi's "China Dream". The successive interventions in the ensuing meltdown were as much to restore market confidence as to spare the party leaders political embarrassment.

That Mr Xi is committed to economic reforms, I have no doubt. The fact that economic stimulus is now taking precedence over reforms, ahead of a crucial party congress, is not a strategic retreat but a tactical political adjustment. China's leaders are fully aware of what the problems are even though they may not be able to overcome them quickly. As Mr Xi said: "What China needs is a higher quality and efficiency of economic development by successfully addressing the problem of unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable development."

And he emphasised: "Like an arrow shot that cannot be brought back, we will forge ahead against all odds to meet our goals of reform."

But Mr Xi the archer may be aiming at a different target rather than the market. China is not a normal market economy as the state is a dominant player in the economy.

His overarching reform goal is not to transform the "socialist market economy" into a normal market economy, despite his recognition of the "decisive role" of the market in allocating resources.

Mr Xi's goal is to harness the power of the market to make the economy more efficient but not to displace the "socialism" in it. The state will continue to play a "leading role" in the economy. Whether he can get the balance right between the visible and invisible hand, so as to achieve a more productive economy while maintaining party control of it, may be the contradiction that defines his time.

That he is still grappling with this is reflected in the cautious incrementalism that has characterised his economic reforms. The good news is, if history is any guide, in the last 40 years, China's leaders have, when confronted with large economic challenges, responded not in small ways but with bold actions to further open up the domestic economy.

Labour liberalisation in the 1980s. Housing liberalisation in the 1990s. And today, the ongoing financial liberalisation. This is the mother of all liberalisations, not just because of its complexities and incendiary risks but its criticality in improving the overall efficiency of China's economy. That this is proceeding under Mr Xi's watch gives hope that he, too, will prove to be a bold archer.

• The writer is executive chairman of APS Asset Management and senior adviser to John Swire & Sons.