Several years ago, Mr Doug Lemov began studying videos of excellent teachers.

He focused not on their big strategies, but on their microgestures: How long they waited before calling on students to answer a question (to give the less confident students time to get their hands up); when they paced about the classroom and when they stood still (while issuing instructions, to emphasise the importance of what was being said); how they moved around the room towards a distracted student.

In a piece on Mr Lemov for The Guardian, writer Ian Leslie emphasises that these subtle skills are often not recognised or discussed by those who talk about education policy, or even by those who evaluate teachers.

Mr Leslie notes that the Los Angeles school system tabulated the performance of roughly 6,000 teachers using measures of student achievement.

The best performing teacher in the whole system was a woman named Zenaida Tan. Up until that report, she was completely unheralded. The skills she possessed were invisible.

In part, Mr Lemov is talking about the skill of herding cats. The master of cat herding senses when attention is about to wander, knows how fast to move a diverse group, senses the rhythm between lecturing and class participation, varies the emotional tone. This is a performance skill that surely is relevant beyond education.

This raises an important point. As the economy changes, the skills required to thrive in it change, too, and it takes a while before these new skills are defined and acknowledged.

For example, in today's loosely networked world, people with social courage have amazing value. Everyone goes to conferences and meets people, but some people invite six others to lunch afterwards and follow up with four carefully tended friendships. Then, they spend their lives connecting people across networks.

People with social courage are extroverted in issuing invitations but introverted in conversation - willing to listen 70 per cent of the time. They build not just contacts but actual friendships by engaging people on multiple levels.

If you are interested in a new field, they can reel off the names of 10 people you should know. They develop large informal networks of contacts that transcend their organisation and give them an independent power base. They are discriminating in their personal recommendations because character judgment is their primary currency.

Similarly, people who can capture amorphous trends with a clarifying label also have enormous worth. Philosopher Karl Popper observed that there are clock problems and cloud problems. Clock problems can be divided into parts, but cloud problems are indivisible emergent systems. A culture problem is a cloud, so is a personality, an era and a social environment.

As it is easier to think deductively, most people try to turn cloud problems into clock problems, but a few people are able to look at a complex situation, grasp the gist and clarify it by naming what is going on.

Such people tend to possess negative capacity, the ability to live with ambiguity and not leap to premature conclusions. They can absorb a stream of disparate data and rest in it until they can synthesise it into one trend, pattern or generalisation.

Such people can create a mental model that helps you think about a phenomenon.

As Baptist preacher Oswald Chambers put it: "The author who benefits you most is not the one who tells you something you did not know before, but the one who gives expression to the truth that has been dumbly struggling in you for utterance."

We can all think of many other skills that are especially valuable right now.

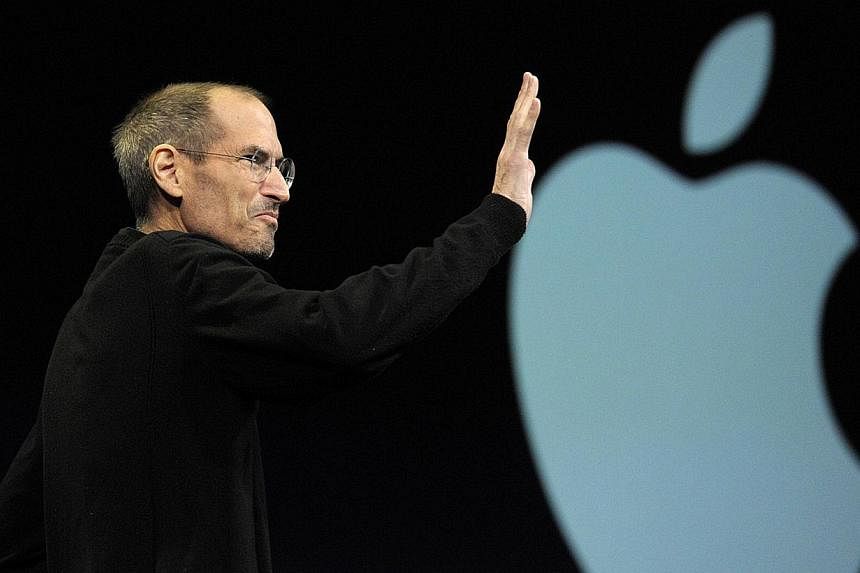

Making non-human things intuitive to humans: This is what Steve Jobs did.

Purpose provision: Many go through life overwhelmed by options. But a few have fully cultivated moral passions and can help others choose the one thing they should dedicate themselves to.

Opposability: Author F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: "The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function." Many people I meet believe this is the ability their employees and bosses need right now.

Cross-class expertise: In a world dividing along class, ethnic and economic grounds, some people are culturally multilingual. They can operate in an insular social niche while seeing it from an outsider's perspective.

One gets the impression we are confronted by a giant cultural lag. The economy emphasises a new generation of skills, but our vocabulary describes the set required 30 years ago. If only somebody could just identify the skills it takes to give a good briefing these days, that feat alone would deserve the Nobel Prize.

NEW YORK TIMES