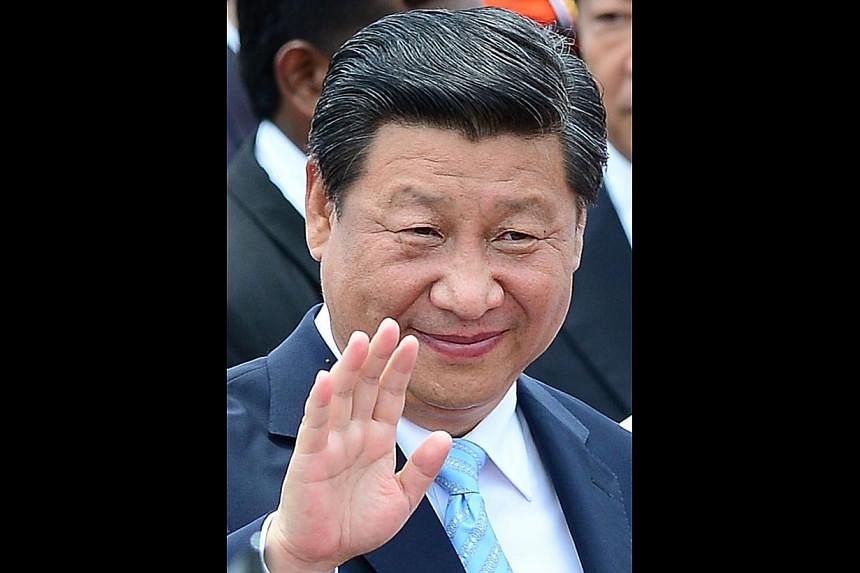

China's President Xi Jinping visits India today, the last leg of a three-nation tour of South Asia. While his hosts welcome opportunities to deepen economic ties with China, they remain wary of Beijing's true intentions.

China's footprint in South Asia has increased considerably over the past decade.

The astonishing speed and unprecedented scale of its rise have been truly transformative, coming even as the likes of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have made important strides of their own in terms of poverty alleviation and human development.

Yet, while China has opened up economically, it has remained closed politically, a quality that could still prove limiting. For example, although China is well integrated into global institutions, it has not always behaved like it is invested in the international system or satisfied with the territorial status quo.

Its recent actions regarding its disputes with Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines and India have only added to its neighbours' concerns. This being so, China is squarely at the centre of Asia's enhanced economic integration and the region's increased political volatility. Amid this backdrop, President Xi will have plenty of positives to offer on his tour.

For starters, China offers an unparalleled ability to finance and execute large-scale infrastructure projects, from ports and dams to highways. As domestic demand evaporates in China, South Asia will be a natural investment destination for mega-projects.

Indeed, China's involvement in projects in Pakistan and Sri Lanka can be widely replicated, especially in India, where the demand for infrastructure will likely be in the trillions of US dollars over the coming decades.

Second, China provides valuable support for developing countries seeking a greater voice on the international stage. This extends to financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, as well as to other groupings such as Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

Institutionally, the interests of China and various South Asian states often align in not insignificant ways.

Third, for many South Asian countries - such as Sri Lanka, which has been criticised for human rights violations, or India with respect to climate change - Beijing is seen as an important ally in defending their sovereignty. Beijing, which is also sensitive about its sovereignty, has occasionally cooperated with these countries in the face of international condemnation.

Fourth, for countries denied access to sensitive military technology by the United States and its allies, or have apprehensions about costs, China offers a cheap source of military equipment and technology. In fact, over the past five years, Pakistan and Bangladesh have been the two largest recipients of Chinese arms.

Finally, and most importantly, as China transitions from an export-led economy to a consumer-driven one, its market represents a potentially lucrative export destination for the gradually industrialising economies of South Asia.

All this means that the countries of South Asia, including India, have a large and growing stake in China's successful rise. But the immense opportunities afforded by China's rise will inevitably be tempered - in various ways and to varying degrees - by several constraints.

The first is the lack of transparency in China's national politics, civil-military relations and military modernisation.

Nationalism is a characteristic of every country, but China's opacity blurs the line between how much it is a self-serving

tool of elites and the extent to which it is organic. Greater transparency, simply speaking, would generate more trust in Beijing's intentions.

Second, China's recent intensification of its various territorial disputes is problematic, and makes Beijing's statements pledging regional cooperation appear insincere. Should Beijing's actions remain in line with its declarations of peaceful coexistence, it would do much to reassure its neighbourhood.

And third, China's economic practices are not always fair and balanced. It still has to shake its tag as a mercantilist power that controls capital flows, discriminates against imports and lacks an independent monetary policy. Ensuring a level playing field would require Beijing to take several steps, including lowering non-tariff barriers to its market.

In his interactions with South Asian leaders, Mr Xi would do well to not just highlight the incredible opportunities afforded by greater cooperation and integration with China. He should also address what are sometimes real concerns. In the midst of a radical political and economic transition at home, and facing the risk of deteriorating relations with the United States, Japan, and many states in South-east Asia, China has an opportunity to show that, in this one part of the world at least, it can be a responsible stakeholder.

The writer is a fellow with the Asia Programme of the German Marshall Fund in Washington DC.