A national day that's been marked for over 80 years.

The launch of an epic movie based on events 700 years ago, with one of the most lavish budgets for a Bollywood film.

A new museum displaying maps, letters and newspaper articles.

All three developments have made headlines over the past week.

In better times, they would have been occasions for celebration in Australia, India and Japan, respectively.

Yet they have drawn strong condemnation and protests, with repercussions for communal as well as regional harmony.

History and how it is portrayed have long been divisive issues within and between countries.

But in an age when fake news is gaining ground and facts are contested, history - and different takes on it - appears to have resurfaced as a battleground.

And it is not just facts or the significance of events that are called into question.

Those mired in these debates appear to have made them a battleground for contemporary anxieties and grievances over multiculturalism and identity, with competing groups insisting that their side of the story should be the prevailing truth.

Take the heated debate over Australia Day, which has been celebrated on Jan 26 for decades.

The date on which British colonists first set foot on Australian soil in 1788 has also been marked by some as a day of mourning or "invasion day" for Aboriginal Australians and the destruction wrought to their way of life.

Australia Day commemorations have evolved - the National Australia Day Council notes that the date has long been a difficult symbol for many Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders, and that it is important to respect their unique status. The council also makes clear that it is a day for all Australians, and that reconciliation, education and history are important aspects of commemorations.

Yet calls to remove Jan 26 as Australia Day have gained momentum in recent years, with sizeable protests this year.

This, in turn, has spawned an ugly backlash from some who insist colonisation was a "good thing" for indigenous Australians.

In a column lamenting this tide of hostility on both sides, The Australian newspaper's editor-at-large Paul Kelly wrote of how the country could be the poorer.

"This debate can break one of two ways: robust differences can generate a better understanding of Australia and its national day, or the upshot can be a destructive orgy of self-interested identity politics leading to a diminished and divided country," he said.

"The volatility of social media, the power of negative politics and the emotional manipulation around 'invasion day' constitute sufficient warning that things could go badly wrong. A nation ignorant of its history or simply unable to handle its history is heading for trouble in the present age of populist and cheapjack disruption.

"The issue is whether we have the maturity to hold together conflicting truths and sort things through, or whether we choose ideological indulgence and cynical zero-sum politics," he added.

"Tearing one truth down in the cause of another is the road to ruin for Australia. Both truths need to be confronted and engaged."

Historical facts mean different things to different people, especially when they are deeply bound up with ethnic or religious identities.

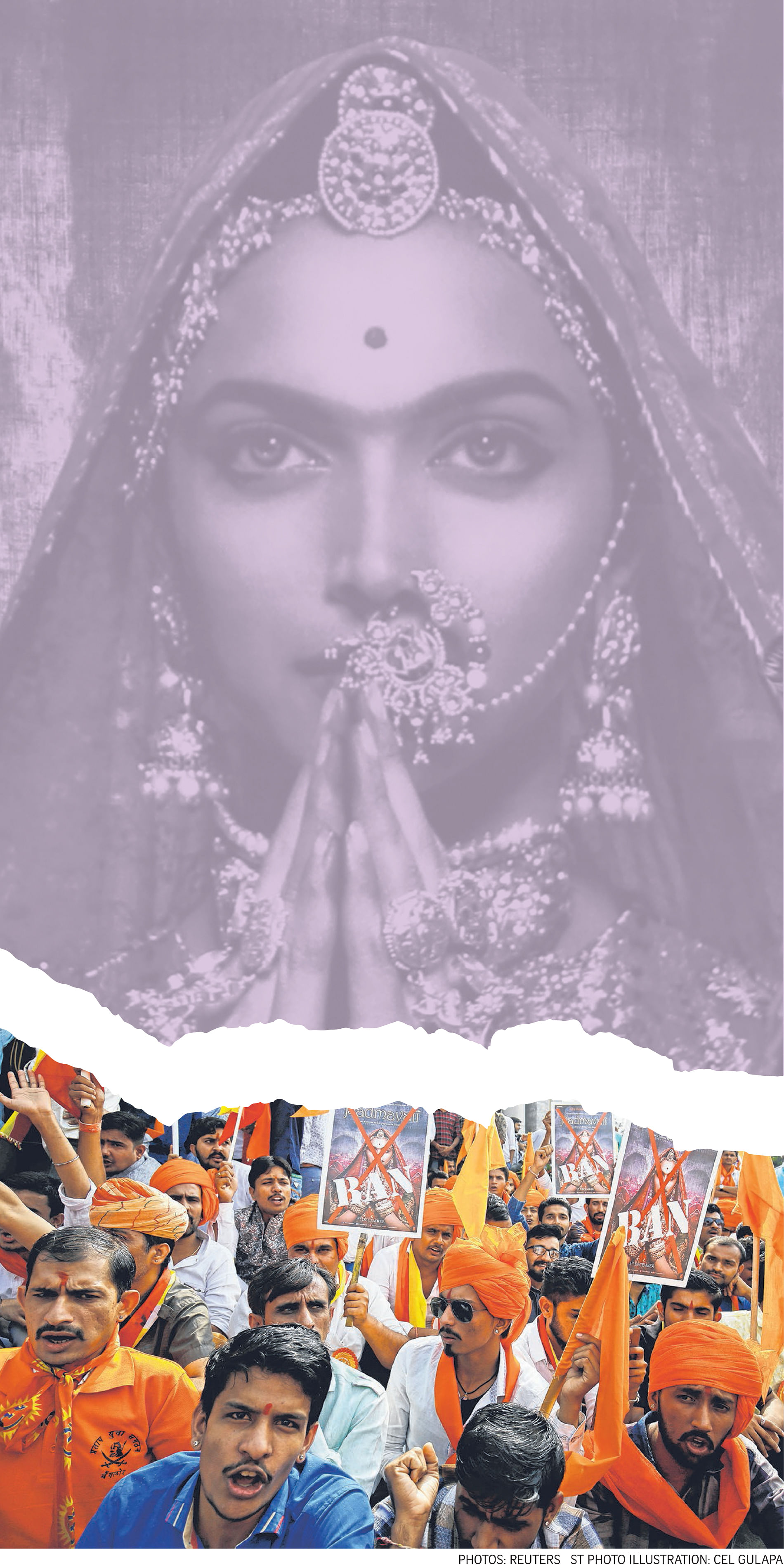

These identities were behind tensions in India where violent protests marked the opening of the Bollywood epic, Padmaavat.

Groups critical of the film took issue with it for distorting history by portraying a Muslim ruler as the "lover" of 13th-century Hindu queen Padmavati of the Rajput warrior clan, but the film-makers deny the accusation.

Protesters burnt tyres and vandalised shops to oppose the film's release, prompting cinema owners in several states to abandon plans for screenings.

This opposition came even after film censors suggested that the movie, originally titled Padmavati, be renamed Padmaavat after the 16th-century poem that the film was inspired by. India's Supreme Court also cleared the way for the film's release and blocked state governments from imposing bans on it.

Bollywood films that touch upon historical relationships between Hindus, who belong to the country's majority religion, and Muslim leaders have become controversial in recent years.

A 2015 film by Padmavati's director about the historic romance between a Hindu king and a princess whose mother was Muslim, titled Bajirao Mastani, stoked similarly strong protests.

Observers note that inter-religious relationships and romances have existed throughout history, but depictions on the silver screen appear to take on a different sheen.

Religious harmony and coexistence have long been the prevailing norm in India, but such controversies, when amplified and misrepresented for political gain, could generate tensions and divide communities.

Ironically, the protests over Padmaavat took place on the day Prime Minister Narendra Modi hosted all 10 Asean leaders for a special summit where he underlined the strong historical ties between both sides - including through religion.

"The Ramayana, the ancient Indian epic, continues to be a valuable shared legacy in Asean and the Indian subcontinent," he said. "Other major religions, including Buddhism, also bind us closely. Islam in many parts of South-east Asia has distinctive Indian connections going back several centuries."

These shared cultural links have created distinctive Hindu, Buddhist and Muslim traditions in South-east Asia that have historically also been tolerant.

Yet there are concerns that such disputes over history, if they spread, could disrupt harmony in this region too.

History has also long divided nations. And in East Asia, it continues to cast a long shadow.

Take Japan, where a government-sponsored exhibition highlighting Japanese sovereignty over islands with disputed claims by China and South Korea opened its doors in Tokyo last Thursday.

The Japan Times reported that while the exhibition is likely to draw praise from right-leaning politicians, the opening takes place at a delicate time for Japan's relations with both its key neighbours. On display are historical documents - maps, letters and newspaper articles, among others - highlighting the official position that the Senkaku or Diaoyu islands, controlled by Japan but claimed by China, and Takeshima or Dokdo, controlled by South Korea but claimed by Japan, are parts of Japanese territory.

The newspaper quoted a 70-year-old Tokyo resident as saying: "It is important to debate these topics from an objective point of view using facts."

However, these facts have created friction - China has rebuked Japan, and South Korea called for the museum to be closed.

The issue is set to remain fraught for the foreseeable future.

People have a right to stake claims to the histories they want celebrated, or are opposed to.

Those calling for Australia Day to be scrapped, Padmaavat to be banned, or the museum to be celebrated may well have strong arguments to back their cases; and it is not for outsiders to determine the merits of these cases.

But they should also realise that their actions could well be met with equally vigorous responses - and result in consequences that could spiral out of control, from tourists rethinking their travel plans to further tensions in a region that could do with less of them.

Instead of solving present-day problems, fights over history may well end up perpetuating divisions well into the future.