The recent news about Russia's state-sponsored doping of its elite athletes has set tongues wagging and fingers tapping (across the blogosphere). When I phoned sports columnist Rohit Brijnath, he was already wading into his article "Fighting cheating is the duty of stars, nations, clubs, fans", which was published the next day on Nov 11 in The Straits Times.

He offered a factually comprehensive view of what doping involves in the current era. Where he and I differ is that his enthusiasm for sports stems from an enchantment of the superlative performance the human body appears to have endless capacity for.

That enthusiasm is justifiable only if one accepts the ultimate purpose in sports is what the Olympic creed stands for: "The important thing in life is not the triumph, but the fight; the essential thing is not to have won, but to have fought well."

Conversely, if the purpose is simply to win at any cost or to set records with the aid of any means, the game itself - based on time-honoured sporting values - then becomes secondary. That is hardly something worth rooting for.

My enthusiasm for sports is more basic and practical. Physically active sports pursued in moderation have multiple health benefits to humans. For that reason alone, I would encourage all who can to participate physically in a sport that they enjoy, for its own sake. My idiosyncrasy is that I have developed an addiction to punishing my own body by pushing it beyond its limits to fulfil my private goals. However, to fixate on performance enhancement to win public glory or strike a bonanza is to step onto a slippery slope.

The reasons against doping are the health risks of performance-enhancing drugs, the undermining of equality of opportunity for athletes, and the eventual destruction of drug-free sports as a global norm for competitors and the general public alike.

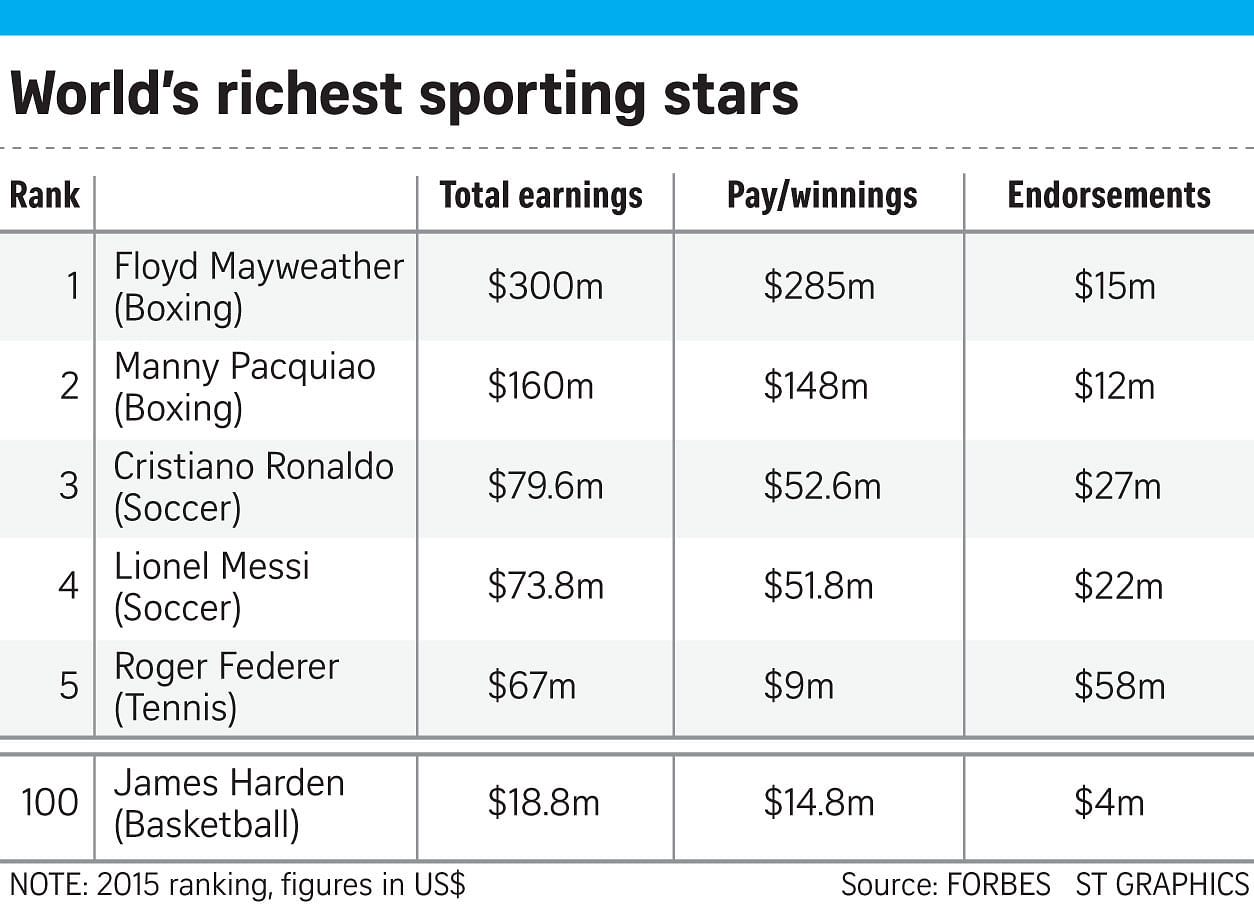

My personal antagonism towards doping in sports is not just over the health risk of performance- enhancing drugs. What I am most strongly against is the way society makes superstars of elite athletes who win. This distorts our appreciation of sports and the rules by which sports ought to be played. I also feel a sense of outrage at the massive earning power of star athletes which distorts the basis upon which work performance should be rewarded.

The big bucks stem from the overwhelming global attention that such stars command. Such attention is an almost inevitable outcome of the human need for entertainment and the diversion of the circus, once needs like food and shelter are fulfilled.

Sports industries are now major participants in creating and maintaining a daily circus for people who would otherwise be bored. The competition of the marketplace boosts rewards for the champions of "cirque du sport"; and higher stakes boost the willingness to take bigger risks.

Just study the table above, which shows how much top-drawer athletes earned last year from participation in their sports. Notice not only the unbelievable incomes of the top five earners but also that of the person at the bottom of the top 100 list. James Harden, the 100th top earner, makes US$18.8 million (S$26.6 million) a year. How many of us can say we would not be tempted to cheat a little for that kind of money? Agreeing to bend the rules might become an easier choice to make when a state-appointed or other competent physician is willing to supervise the doping to minimise the medical risks.

Not all superstar athletes dope, but the table gives an indication of how big the temptation can grow for those in the top ranks of athletic performance. It is not far-fetched to postulate that many might have succumbed, wittingly or unwittingly, to performance-enhancing substances of one sort or another. It's plausible that some of these substances might even have been processed to a high degree to avoid detection. To reach the top, it's safe to assume that few are relying on chicken soup alone.

The best illustration of this is the difficulty in finding a replacement to be proclaimed the "clean" winner of the seven Tour de France races after Lance Armstrong admitted to doping; it was close to impossible. The biggest argument for Armstrong's behaviour, spurious as it is ethically, is the belief that all other riders were doping.

A recent analysis of the "EPO Era" (named after the most commonly used drug, Erythropoietin) shows that the "everybody was doing it" defence may not be that far removed from reality. Teddy Cutler of SportingIntelligence.com recently took an excellent detailed look at all the top cyclists from 1998 through 2013 and whether or not they have ever been linked to blood doping or to a doctor linked to blood doping.

During this 16-year period, 12 Tour de France races were won by cyclists who were confirmed dopers. In addition, of the 81 different riders who finished in the top 10 of the Tour de France during this period, 65 per cent have been caught doping, admitted to blood doping, or have strong associations to doping and are suspected cheaters.

Other sports are also tainted in varying degrees. When states are complicit, mere suspension from competition won't eliminate the doping scourge. Stricter all-round testing will be necessary. Where organisations and individuals are concerned, it's within the scope of sporting federations to cap the remuneration of star athletes and subject these to stricter auditing. They do not deserve the huge sums of money they so easily command. If this temptation is removed, so will a major incentive to dope.