LONDON • A month after the British shocked the world by deciding to leave the European Union, nothing much seems to have happened. The British pound dipped but then partially recovered. Financial markets swooned but then regained their poise. Economists forecast a recession but the British economy is still predicted to do better than that of most other European countries this year. A lengthy political crisis was also averted: The change of prime ministers from Mr David Cameron to Mrs Theresa May was both swift and smooth.

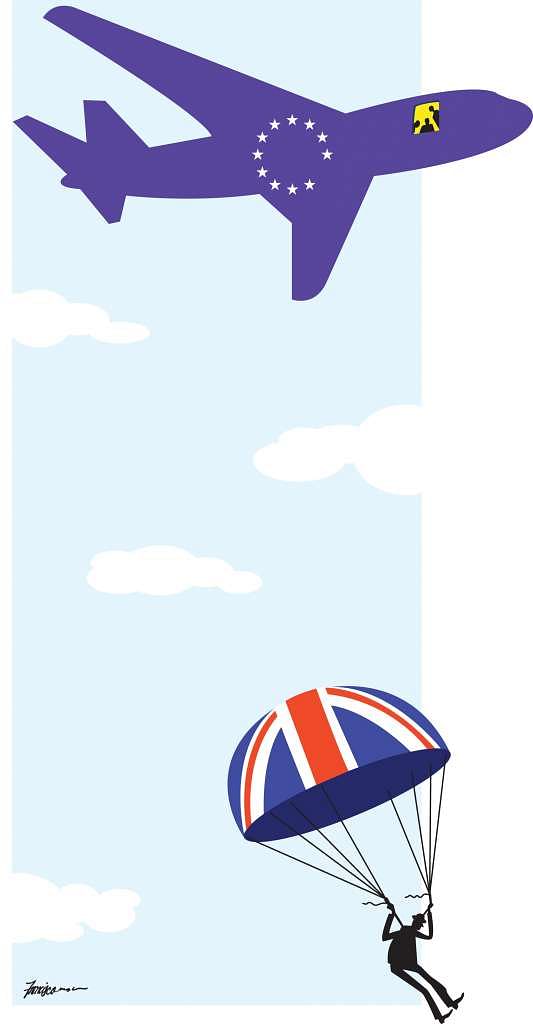

Still, the real importance of seminal events is often only noticeable with the passage of time, and the same may be true in this case. For Brexit - as the process of Britain's separation from the EU is now popularly known - will have a profound impact on Europe as a whole, although not necessarily in ways predicted by many political and economic analysts today.

Despite occasional hopeful headlines in some European newspapers claiming that the British may be regretting their decision to leave the EU, there is no evidence that British voters are experiencing such "buyers' remorse" sentiments. All recent opinion polls indicate that over 85 percent of those belonging to either the pro- or anti-EU camps in the British electorate would be making exactly the same choice if another referendum were held now.

The truly surprising immediate reaction has not come from Britain, but from electorates elsewhere in Europe. In the aftermath of the British vote, senior EU officials gloomily predicted a boost for anti-European sentiments throughout the continent.

In fact, precisely the opposite has happened: Popular support for the EU has soared. In Germany, 81 per cent of respondents say they now support their country's EU membership, a 19 per cent increase on the figure recorded when the question was last asked by pollsters two years ago. In France, support for the EU surged by 10 per cent to 67 per cent. Higher figures have been recorded in practically every EU member state.

The euro, the continent's currency now more frequently associated with austerity than economic stability, is also an unlikely winner from the Brexit vote, at least as far as its popularity is concerned.

The French economy may be stagnant, but 71 per cent of the people of France do not wish to contemplate a return to their old French franc. Italians blame the European currency for their current austerity, but only 43 per cent of them want to restore the Italian lira.

The uptick in support for the EU and its institutions may not last: It appears to be largely prompted by a sheer sense of puzzlement and incomprehension throughout Europe at what the British have done, coupled with an instinctive desire of Europeans to hold on to the institutions they have, out of fears that Brexit may have unforeseen negative consequences.

As the novelty of the Brexit story wears off, this surge of support for the EU may wear off as well.

Still, the reaction throughout the continent is an indication that glib predictions, according to which the EU would break up in the aftermath of Britain's departure, are fundamentally misconceived. In fact, there are good reasons for believing that no EU country will follow Britain's example of holding a referendum on leaving the union.

The chief explanation for this is the historic resonance which the EU has for the overwhelming majority of its member states. For the Germans, the French and the Italians, the union is the only way of escaping from their horrible past, from their previous national tale of dictatorship, war and economic failure. Of course, few in Europe believe that, if the EU were to disappear today, the Germans or the Italians would get back into their military uniforms, take their boots from under their beds and start marching across Europe; those grim days of war are gone forever.

Still, few Italians or Frenchmen believe that their countries would do better outside the EU than inside it. And few Germans would be comfortable leading Europe on their own, which is the only likely outcome from the EU's disintegration.

Meanwhile, for the smaller nations of Western Europe, there is simply no other option but the EU. And for the former communist countries of Eastern Europe, the EU is not about markets but about security, about being reassured that the old ideological division of their continent is gone forever. For them, the alternative to the EU is either to be left in a no-man's land between Russia and the West, or to eventually fall into a Russian sphere of influence, as they have done in one way or another throughout the past century.

No prizes for guessing which option the nations of Eastern Europe prefer.

It is true that, for the first time ever, mass political movements such as France's National Front and the Netherlands' Party for Freedom are touting the possibility of following the British example by taking their countries out of the EU.

But although such movements are increasingly popular, they are also highly unlikely to get their wish.

Mrs Marine Le Pen, the leader of France's National Front, is currently the single most popular leader in her country. However, given France's two-round electoral system, she is virtually guaranteed to be defeated in the second round by whoever stands against her. A similar fate awaits the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, which even if it does well in the country's forthcoming elections, will never be capable to govern on its own, and will therefore have to drop its referendum idea.

Still, Brexit does confront the EU with some pretty serious, if not existential, challenges. The biggest danger is that the appetite for referendums - the one unleashed by Britain - will be used by member states not so much to leave the union but, rather, to escape from duties and obligations they don't like. That is what is already happening in Hungary, where a referendum on immigration is scheduled for October, largely in response to a decision by the European Commission to distribute newly-arriving refugees between the EU member states.

If Hungary votes against admitting immigrants - more or less a foregone conclusion - Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban would use this as a justification for evading obligations imposed by the EU's central bodies on his country. And if the Hungarians succeed in getting away with this defiance, others are guaranteed to follow suit.

Europe may escape another Brexit-style referendum only to face the danger of many referendums of more limited questions, votes which can still destroy European unity.

The air of defiance against EU decisions is now spreading fast. Earlier this month, the French government announced that it will "simply not apply" an EU regulation allowing East European citizens to compete for domestic jobs on more favourable terms. Meanwhile, Italy is threatening to defy EU laws in bailing out its bankrupt banks with taxpayers' money. Seldom has national defiance of the EU been more tempting.

The second big danger for the EU is that a Britain outside the union would still be able to exercise its influence inside the EU. For Britain is not Norway or Switzerland, other European nations currently outside the EU; the British possess Europe's most powerful military machinery, have a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and still enjoy some global clout.

Unless the British remain tied to European foreign policy and security structures, a Britain outside the EU will remain a pole of attraction for individual European countries, which will be tempted to bypass EU institutions and deal directly with the British on security questions which matter to them.

If Poland, for instance, does not like EU policies on containing Russia, the Poles could turn to Britain to get extra support; a push-pull game could develop, and one which will reduce the EU's ability to speak with one voice.

Either way, it's clear that the calm which seems to have descended on Europe since the British voted to leave the EU a month ago is merely a lull before the sharper and far bigger challenges return. And although the EU is most certainly not about to break up, it still needs to avoid a potentially equally tragic fate: that of internal paralysis and defiance by its increasingly unruly member states.