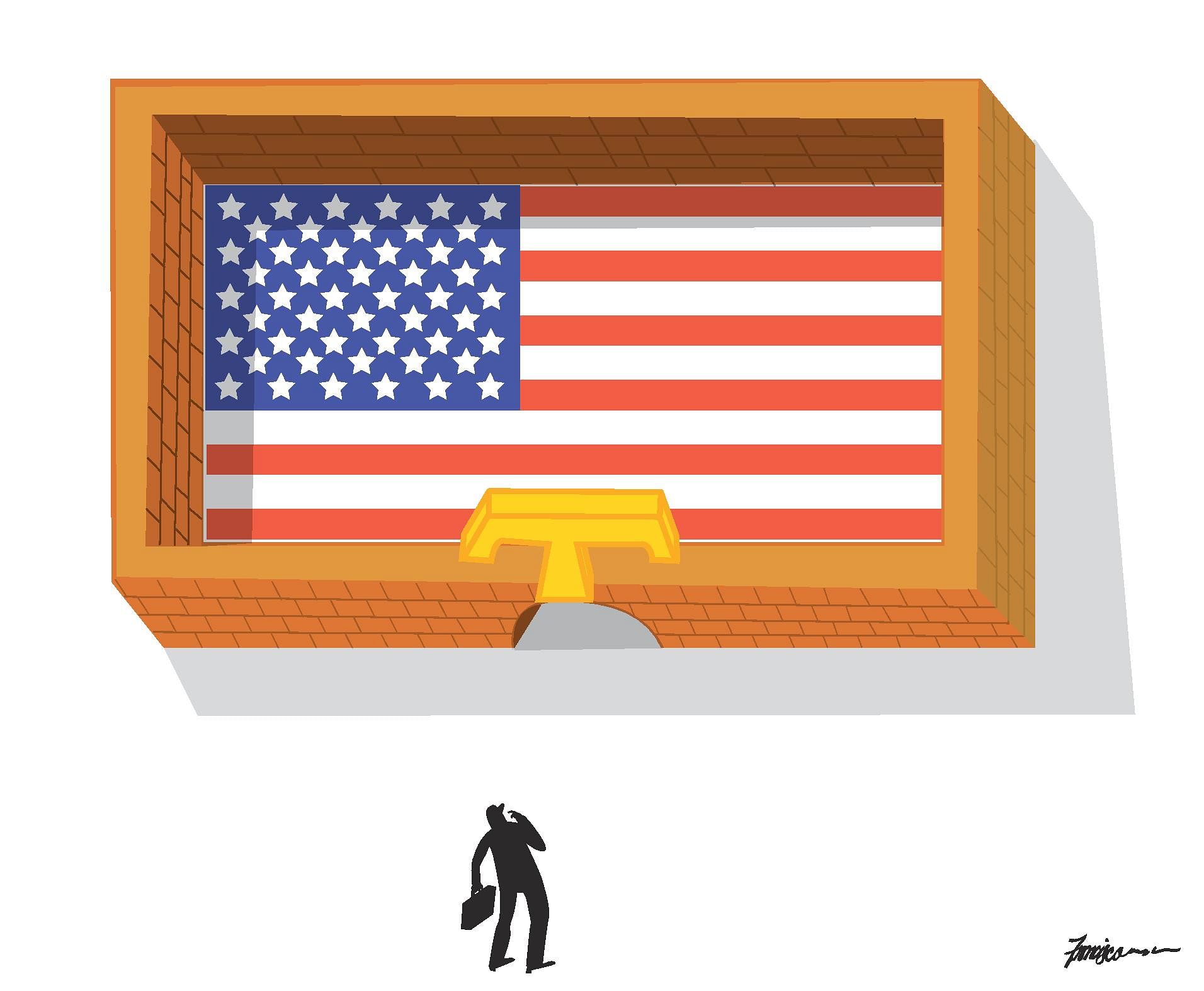

Mr Donald Trump's inauguration as the next US president is less than three weeks away. Judging by his appointment of ardent China hawk Peter Navarro to head a newly formed White House National Trade Council, hard-nosed trade negotiations with US trade partners are in store during his term.

On trade, Mr Trump has promised to withdraw the US' pledge to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a free trade pact that has not been ratified by US lawmakers. And he has called for the US to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico.

Does this spell the end of the TPP? In name and form perhaps. But the US is also unlikely to walk away from a trade pact that accounts for more than 40 per cent of the world's GDP, and leave the door open for the China-backed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a trade deal pioneered by Asean and its free trade agreement (FTA) partners.

"Much of China's economic diplomacy is beneficial, but the hidden cost is that, at this stage, China is not committed to the open trading system that the US had sought to build, and will not likely promote open trade in services or reduction of non-tariff barriers such as subsidies," says Mr Philip Jeyaretnam, senior counsel and regional chief executive at Dentons Rodyk. In short, a regional trade pact that does not involve the US is not desirable.

So one can only hope that the US comes back to the table. But if it does, it will probably try to extract a bigger concession, given Mr Trump's election bluster over international trade. At the same time, the TPP signatories are not likely to bend over backwards for him, so protracted negotiation for a revised trade pact can be expected.

But Singapore need not fret as it can still rely on the numerous free trade agreements that it has with most TPP members and Asean to soften the blow from a potential delay in the implementation of a Trump-shaped TPP. Observers believe that the economic impact for Singapore would be limited given that it already has an open economy and extensive bilateral agreements in place - including an existing FTA with the US.

The only TPP members that Singapore does not have FTAs with are Mexico and Canada, but "our trade flows with these two countries are very marginal", says DBS economist Irvin Seah. "Other TPP members may want to pursue bilateral agreements that are easier to negotiate, and entail deeper commitments. That can keep the torch of global trade liberalisation alive," he adds.

TPP'S PLUSES

Nonetheless, Singapore is pressing ahead with ratification of the TPP, as the pact's fostering of economic restructuring in other countries in the region would raise economic growth rates in Asia, and that would in turn benefit Singapore.

Moving ahead with the TPP could give Singapore companies the benefits of a deep and broad agreement that would give better access to economies like Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, Vietnam, Malaysia, Chile, Peru and Brunei than any existing agreement, says Ms Deborah Elms, executive director of the Asian Trade Centre.

And as an added bonus, American companies that want to continue to compete in Asia will need to be located in Asia, increasing the amount of investment, jobs, technology and resources they will have to devote to Asia, she adds.

Observers concur that without the US, the TPP won't have the same economic heft. But a modified version of TPP may not be so bad as it will include the world's third-largest economy, Japan, and serve as a vehicle for further Asian integration. Despite Mr Trump's vow to pull the US out, Japan went ahead to ratify TPP last month because it might want to assume leadership in developing trade norms in Asia, especially as it sees China as a dominant player in the RCEP negotiations, says law professor Peter Yu of the Texas A&M University School of Law.

"Japan may want to hedge against the chance of the new US administration changing its mind or the possibility of having a watered-down version that will be acceptable to them. Finally, it may want to induce other countries to ratify the agreement, thus pressuring the new administration to ratify the TPP," he says.

And there are good reasons for Mr Trump to come back to the TPP table. The RCEP, which excludes the US, could put US exporters at a disadvantage, given the possible tariff reductions between China, Japan and South Korea, which are among the United States' top six trading partners, HSBC economist Joseph Incalcaterra says.

Increasingly, Asia's growing intra-regional integration is providing a buffer against a protectionist America, Oxford Economics economist Priyanka Kishore says.

"Traditionally, Asia's intra-regional trade was largely concentrated in intermediate goods, with US and Europe accounting for the bulk of final demand. But recent data from the IMF show that there has been a shift in the trend.

"China's share in Asia-ex China's final demand was the same as that of the US in 2011, and it is expected to rise further. Similarly, Asia-ex China accounted for almost 30 per cent of China's final demand. This is a welcome development, and not unexpected given the subdued growth in the West in recent years," Ms Kishore says.

LOST OPPORTUNITY

All things considered, the withdrawal of the US, the largest economy in the TPP, will represent a loss of opportunity for Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and, to a smaller extent, Singapore, Mr Incalcaterra says.

Malaysia and Vietnam stand out among the TPP members without existing US FTAs. Through the TPP, Vietnam and Malaysia were projected to enjoy some of the largest gains in exports, of 30.1 per cent and 20.1 per cent respectively, from access to protected foreign markets. They were also forecast to enjoy the largest boost to real incomes, by 8.1 per cent and 7.6 per cent respectively, by 2030.

More limited in scope than the TPP, the RCEP focuses mainly on tariff reduction and services liberalisation, compared to the TPP which goes into areas such as business conditions, raising environmental and labour standards, regulations and protection of intellectual property.

According to Mr Incalcaterra, this means that welfare gains from the RCEP will not be as large as those from the TPP. But the benefits of RCEP will be more equally shared across Asean, since all 10 members are signatories to the pact, together with India, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and China.

Singapore is expected to benefit the least from the RCEP, as it already has FTAs with all RCEP members, either through Asean or direct bilateral channels, Mr Incalcaterra says.

In contrast, Vietnam is expected to benefit the most, from new trade agreements and gains coming from increased sourcing of production from Japan, Korea and China.

However, the fact that the RCEP doesn't focus on some of the lofty goals of the TPP doesn't mean it isn't an ambitious undertaking. For example, the RCEP links the world's two most populous countries, China and India, in a trade deal for the first time, while also pairing Asia's two largest economies, China and Japan.

"The RCEP includes China, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand and other emerging countries - countries that have been left outside the TPP. Although the RCEP standards may be lower than those in the TPP, we cannot ignore the benefits provided by these non-TPP markets," Mr Yu says.

The RCEP could also be key to the ambitions of the Asean Economic Community (AEC) by helping improve the group's access to overseas markets. And as China leverages on the RCEP to push its "One Belt, One Road" initiative, China's fourth-largest export partner, Asean, should benefit, economists say.

Initiatives like the RCEP can provide a buffer against an increasingly protectionist America, especially in light of Mr Trump's intentions to lower US trade deficits with other countries, either through negotiations or through the imposition of tariffs and trade sanctions.

Last year, the US ran a deficit of US$69.5 billion with Asean - a shortfall of US$76.7 billion in goods that was partially offset by a US$7.3 billion surplus in services. That's the third-largest deficit run by the US, after China and Germany.

According to HSBC, total trade between Asean and the US is not insignificant, with the exchange of goods totalling US$212.3 billion in 2015 - making Asean the US' fourth-largest trading partner behind China, Canada and Mexico.

The good news is that Asean has hardly figured in Mr Trump's policy plans, so far. Instead, he and Mr Navarro have zeroed in on China from the outset. But it remains to be seen if the region's sizeable surplus with the US will eventually come under greater scrutiny by the Trump administration.

And if it does, whether they will take a passive position of decreased engagement with the region, or a more aggressive approach to reduce the US trade deficit with Asean.

Either way, as Asean growth moderates in an already weak external environment, a protectionist US is an additional challenge that Asia-Pacific countries can hopefully counter by keeping the torch of free trade alive in the region.