Since the beginning of this century, signs have been appearing that seemed to herald the erosion of "the West" as the fulcrum of world order. Last year, with Brexit, Mr Donald Trump and other vicissitudes, the signs became unmistakable.

The narrative of the 21st century will be written in Eurasia. This does not mean a new Eurasian world order, but flagrantly illustrates what can be termed a chaotic global transition to uncertainty: new actors, new stages, new technologies, new demographics, new passions, new geopolitics, new military balances, and so on.

I arrived in Moscow on Saturday Sept 30, and on Sunday morning, went walking in Red Square while also visiting the big department store Gum. I first visited Moscow in 1965.

Though I have returned often since, I had not been there for some time. The big shock - though with the benefit of hindsight it should not have been a surprise: Masses and masses and masses of Chinese tourists. There was none in 1965! Indeed this was smack in the middle of the vitriolic Sino-Soviet split which, in 1969, degenerated into a bloody border war.

The border is long. Leaving aside Kazakhstan and Mongolia, countries with which Russia shares immensely long borders (respectively 6,846km and 4,677km), the current direct border between Russia and China is 3,645 km.

Apart from a shared border, however, China and Russia have very little in common. In fact, it is difficult to think of examples of neighbours having such radically different cultures.

Throughout history, relations have hardly ever been warm or close. This has been especially the case since 1703, when Peter the Great founded Saint Petersburg as the capital of the Russian empire looking to Europe. Europe has been an integral part of modern Russian history as Russia has been an integral part of modern European history.

Among the many fascinating questions arising in the current chaotic transition to uncertainty is whether Russia is now looking more to the East, due to the sanctions, the expulsion of Russia from the G-8, and the hostility of European governments following Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea.

This is what President Vladimir Putin would seem to be heralding, including last month through his hosting of the Eastern Economic Conference in Vladivostok.

TWO PROMINENT PLAYERS

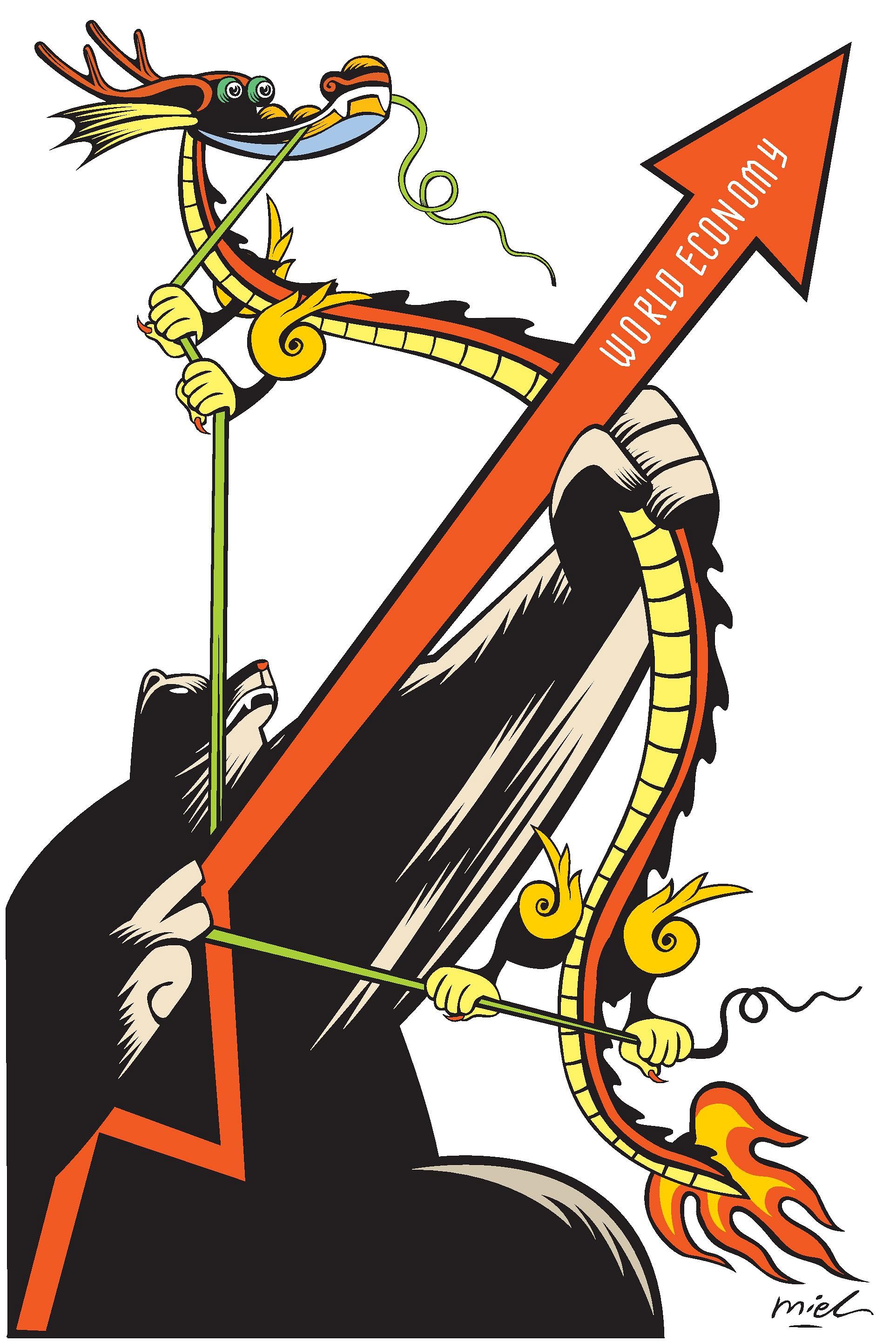

Among the actors that will determine the narrative of the Eurasian 21st century, obviously Russia and China will play prominent parts. How they get on - or not - will also have a huge impact. So watch this space.

The scenario is by no means clear. For one thing, whereas China is a rising empire, Russia is a declining empire. As a Russian friend put it to me in conversation in Moscow, empires never exit gracefully. Look at the Ottoman empire or, for that matter, the British empire with the continuing warfare in post-partition Kashmir. Collateral damage from imploding empires is often, arguably invariably, considerable.

Today, Russia aspires to being a geopolitical giant, but is an economic dwarf. China, whose GDP is 10 times greater than Russia's, had become a global economic giant and now is in the process of flexing its geopolitical muscle.

A second shock I had in my recent visit to Moscow - which, however, once again with the benefit of hindsight should not have been a surprise - is how much Mr Mikhail Gorbachev is reviled.

The shock came as on my first night in Moscow I was dining at Café Dr Zhivago, where I had brought with me the 800-page biography by William Taubman entitled Gorbachev and displaying his portrait on the cover.

When they saw this, I was harangued, albeit in a friendly way, by a group of Russian millennials who could find no words strong enough to express their dislike and contempt for the man.

'THE RUSSIANS DON'T GET IT'

In 1991-1992, some milestone events took place that put Russia and the Gorbachev revulsion today in perspective. In 1991, Indian Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao undertook radical economic reforms, thereby abandoning the "Hindu rate of growth" in which it had been languishing for decades.

Following the cataclysm of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, in 1992, strongman Deng Xiaoping went on his historic Southern Tour thereby kickstarting the revival of the Chinese economy, leading to the superlative growth that ensued.

At the western end of the Eurasian continent, in 1992, the Maastricht Treaty was signed leading to greater European unity.

Much of the world seemed to be moving confidently forward.

What a contrast with Russia. In 1991, the Soviet empire imploded, chaos followed, while "shock therapy" reforms were administered by Mr Yegor Gaidar which resulted, among other things, in massive poverty and hyper-inflation. As was commented when the reforms' volcanic dust began to settle, lots of shock, but where was the therapy?

The economy never recovered. The 1990s are seen by many Russians as an unmitigated catastrophe. On the economic front, things have not improved much since.

As a Hong Kong Chinese friend put it at a recent roundtable forum in Chamonix, when comparing the Russian and Chinese economies, "the Russians just don't get it" - the "it" meaning the market. China may still be a communist state, but there a sizeable chunk of the economy is market-driven and entrepreneurialism is rife.

Also, many Chinese enterprises, including small and medium-sized ones, are plugged into the global market and looking to export (and increasingly to acquire assets). In Russia, the export sector is dominated by a small handful of colossal players.

On the political front, with Mr Gorbachev and Mr Boris Yeltsin reviled, Mr Putin appears as somewhat of a saviour. There are, of course, highly divergent views, but in comparison with his predecessors, he has restored a degree of dignity and respect to Russia. This arises in good part from another humiliating crisis of the 1990s, the degree with which the West treated Russia with derision and contempt. There was no significant reaching out on the part of Europe or the United States. There was no sense of Russian pride and the ways in which the Russian soul could be wounded. Feared in the Cold War, Russia was denigrated in the post-Cold War.

Russian political leaders and policymakers made many mistakes. But the West also botched it. It was singularly insensitive and unimaginative. The opportunity of fashioning a new world order was lost.

How will the Sino-Russian relationship fare in the decades ahead? At this stage, it can be said that political relations are very good, as appears to be the case in the personal relationship between President Xi Jinping and Mr Putin. There are growing cultural ties. No one plays Prokofiev's Piano Concerto as divinely as the Chinese virtuoso Lang Lang. But economic links remain weak. Russians are potentially excited by the opportunities that may arise from the Belt and Road Initiative, though so far results are meagre. Ultimately, no matter how cordial the political and cultural relations may be, economic ties will obviously matter greatly.

The way forward is not obvious. But, as in the famous Chinese proverb, a long journey begins with a single step; an important and potentially very promising step was recently taken with the establishment of a Joint Russian-Chinese University in Shenzhen. There is the potential of the new generations creating a solid Sino-Russian edifice.

How the Dragon and the Bear get on will have a huge impact on prospects for Eurasia, and ipso facto for the planet.

So, as I said, watch this space. I shall be returning frequently.

•The writer is emeritus professor of international political economy at IMD business school, with campuses in Lausanne and Singapore, and a visiting professor at Hong Kong University. He writes monthly for the By Invitation column.