LONDON • European leaders hoped that difficult winter weather conditions would give them some respite from the masses of refugees now besetting their continent; the sea routes from Turkey to Greece, the preferred entry point for asylum seekers from the Middle East, become impassable during this season.

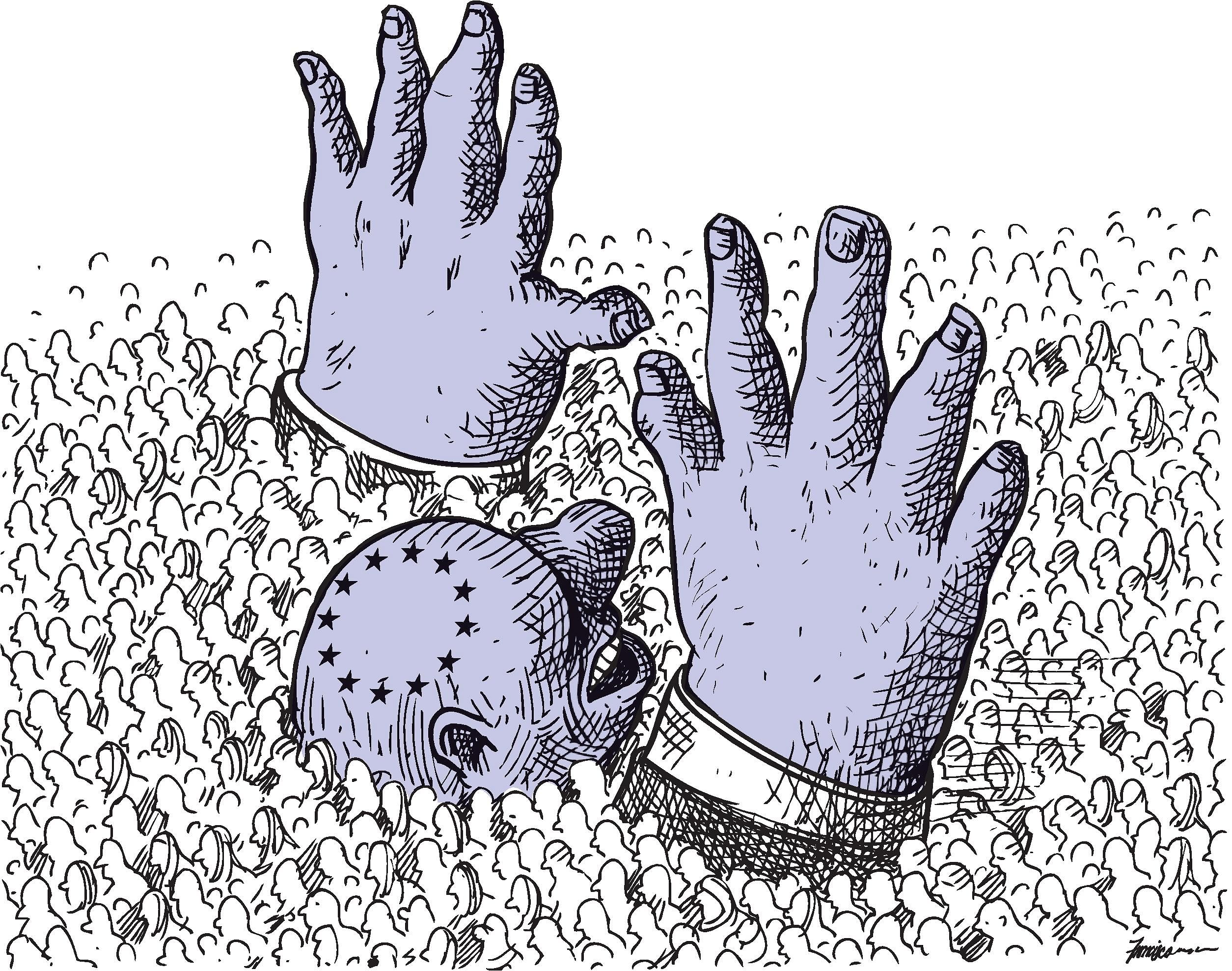

But neither low winter temperatures nor the measures taken by some European Union governments aimed at discouraging new arrivals appeared to have made the slightest bit of difference. Since the start of this year, around 120,000 migrants have already made it to EU soil, roughly four times the number recorded during the comparable period last year. And once spring returns, this human flood will only intensify. Predictions are that total migrant arrivals from the Middle East alone could easily top 1.5 million by December.

This is the moment when EU governments should draw together, since not one of them is capable of handling a crisis of this magnitude on its own. But instead, Europe's politicians are at each other's throats; Greece has even resorted to the extraordinary measure of recalling its ambassador from a fellow EU member-state in a spat over the handling of migrants. In effect, Europe is sleepwalking into a major policy disaster which can tear apart the continent's existing political structures. And all this could happen in, literally, a week from now.

Two arguments dominate the debate about Europe's current immigration crisis: that it is all due to the war in Syria, and that it was made much worse when German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced last year that her country would accept all newcomers. But although both arguments are partially correct, neither offers an accurate explanation of Europe's predicament.

The Syrian civil war, now in its fifth year, has dislocated at least five million people, yet in reality, fewer than half of those currently crossing into Europe are from Syria; the rest come from places as far afield as Pakistan or Afghanistan, as well as from nearby Balkan countries which are not in the EU.

And many don't fit the traditional image of refugees. They have enough cash to pay unscrupulous boat operators to take them to Europe and upon landing on Europe's shores the migrants' first objective often consists of just finding a local SIM card and charging point for their iPhones.

And while it is true that by opening her country's borders, Dr Merkel transformed her country into a magnet for migrants, it is also true that by the time she made that fateful decision last year, the migratory pressures were already unstoppable.

PASS THE PARCEL

Europe's real mistakes lie elsewhere. They started with a refusal to acknowledge the challenge represented by the rising human tide, which was evident to all for at least a decade.

The mistakes were then compounded with a refusal to accept that the traditional procedures of dealing with asylum seekers, which put all the burden on the first European country where they landed and required a complex legal system of examining asylum applications, was simply irrelevant in today's world.

And they ended with a desperate attempt to cling to the noble idea of the free movement of people inside Europe, notwithstanding evidence that this was transformed into a free ticket for the world's asylum seekers and economic migrants.

The result was a disgraceful pass-the-parcel game in which no European government tackled the fundamental problem of migration, but each country tolerated migrants, as long as they shifted along to the next country. Governments simply abandoned even their basic obligation to document the migrants, for keeping records meant taking responsibility.

Yet this bizarre approach may be nothing in comparison with Europe's forthcoming political mayhem. Dr Merkel knows that if the flow into her country is not stopped soon, she will face a rebellion not only from the electorate, but also within her own party. However, she is still not ready to admit that she was either wrong in handling the migrants' question, or that she needs to change course now. Instead, she clings to two other policies - a demand that all other European nations share the burden of settling asylum seekers, plus an offer of money to Turkey, in return for that country sealing the migrants' preferred route.

Both policies are irrelevant. For as Hungary has recently shown by calling a snap national referendum on the matter, there is no chance of other European countries agreeing to admission quotas on migrants. And Turkey demands a far higher price than just money for its cooperation - it wants Europe to support Turkish policies in the Middle East, something few EU governments are prepared to countenance.

BACK TO BORDERS

What is happening instead is that each European government is now rushing to impose border controls in order to avoid the possibility that, when the Germans finally do close the door to migrants, others would be left with migrants on their soil. In effect, last year's European game of pass-the-parcel, which entailed migrants being shunted from the eastern part of the continent to its western parts, is now being reversed with migrants being pushed back eastwards. The so-called Schengen arrangement, which promised open borders, is dead, although nobody wants to admit this, or attend its funeral.

In theory, the EU could survive unscathed with border controls, as it has done in the past, before the Schengen agreement was invented. Furthermore, the Schengen accord does envisage the possibility of its suspension in emergency situations, so EU states could claim that the long-term prospects of a border-free Europe remain undiminished, even if national police forces restart checking passports.

Still, the consequences for Europe will be dire. The reimposition of border controls will give impetus to those who want to attack the very concept of the free movement of labour inside Europe - why stop at keeping Middle Easterners out, when you can also keep the East Europeans out as well?

The reintroduction of border controls will also do nothing to silence Europe's extreme right-wing parties, which will be able to claim, with some justification, that their anti-migrant position is vindicated; France's populist National Front is now asking not only for sealing the country's borders, but also for the expulsion or "repatriation" of existing migrants.

More importantly, the result of the reimposition of border controls would be that Greece, which is the entry point for the current flows, will become the dumping ground for all incoming migrants, or that the Greeks resort to draconian measures nobody else envisages, such as pushing the migrants back to sea; "Greece will not accept unilateral moves; unilateral moves can also be made by Greece" is how the country's Migration Minister Yiannis Mouzalas ominously put it over the weekend. So, border controls are not just a bureaucratic enterprise, but also the start of a new human tragedy.

Nor should anyone underestimate the psychological blow to Europe's self-esteem if the Schengen agreement collapses. For this will be the first time the EU backtracks on a significant effort at regional integration. And, once failed, it is inconceivable that a border-free Europe will be recreated, given the current tensions between countries, and the deep divides between the eastern and western halves of the continent.

Faced with such terrible choices, the EU responded in the only way it knows, by calling an emergency summit, scheduled for a week's time. The continent has plenty of options at its disposal, from agreeing to a simplified procedure for assessing asylum seekers, and right up to the creation of a Europe-wide mechanism for rapid repatriation of those not entitled to asylum, which account for the bulk of those entering the EU. But the collective, cool-headed spirit of cooperation which has ruled the continent for decades has dissipated. And that's not something one summit alone can restore.

The EU has survived many crises. Yet at no time since World War II has it faced such a "perfect storm" of financial, political and humanitarian challenges, all rolled into one. And at no time in the past did the continent seem so determined to sleepwalk straight into a disaster.