LONDON • It took more than nine months between the day the people of Britain voted to leave the European Union and the time British Prime Minister Theresa May issued the official diplomatic note which starts the divorce negotiations between her country and the EU.

But as she did so at the end of last week, it was telling that almost nobody in London accused Mrs May of wasting time by delaying action.

For despite all their posturing and bravado and their reluctance to admit so publicly, all British politicians are keenly aware that Brexit - as the process of separating from the EU is now universally known - remains the most complicated and potentially dangerous task undertaken by Britain since the country dismantled its empire over half a century ago.

Like decolonisation during the 1950s and 60s, Brexit will sap the attention of a vast bureaucracy, as well as requiring huge government financial resources, infinite political wisdom and a much longer time than anyone predicted. It will also need plenty of sheer luck to work, and each false move could spell disaster, for the British and for the rest of Europe.

And, like decolonisation two generations ago, Brexit will force the people of Britain to look again at themselves in the mirror, to decide what country they wish to be and what place should they desire in the world.

BUDGET MATTERS

First, an important caveat and warning. Don't trust anyone claiming to "know" what will happen over the next two years, which is the period allocated by EU treaties to the Brexit process. There is no precedent for this process, and no rule book to be consulted. And there has not been one example in modern European history where countries embarked on deeply controversial diplomatic negotiations and managed to stick to the same negotiating position right until the conclusion of the talks.

All that we can say at this stage is that Britain clearly starts from a position of inferiority: it represents a market of just 65 million consumers, facing an EU which speaks for almost half a billion.

The Europeans are also perfectly justified in insisting that, whatever deal Britain gets at the end of the talks, it will have to find itself in an inferior position to an existing EU member-state; allowing Britain to enjoy most of the advantages of membership while getting out of the EU would be folly.

There is also the fact that EU negotiators control the timetable: if they refuse to budge and no deal is concluded in two years' time, Britain will drop out of the EU anyway. And, contrary to the claim by Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson who recently said Britain "will be OK" in such a case, leaving the EU without a solid agreement would be a disaster.

Duties will immediately be placed on goods travelling between Britain and the EU (10 per cent on cars, for instance, and an average of 20 per cent on agricultural produce) and banking services will lose the ability to sell products into the EU, destroying London's financial prominence.

So, although the British claim not to be frightened of the possibility of ending the Brexit negotiations with no deal, they know this is not an option, and so does the EU. That means that London's room for diplomatic manoeuvre is limited.

However, it's not negligible. The reality is that Britain is the EU's second-largest net financial contributor, and its departure will instantly cut off around 13 per cent of the EU's operating budget. That is one reason why EU negotiators have touted large sums of money - estimates range between €50 billion and €60 billion (S$75 billion to S$90 billion) - which Britain would, supposedly, have to pay as it leaves the EU to cover alleged liabilities; the bigger the bill presented to London, the less the EU has to think about how to reform its budget thereafter.

But the whole discussion about such vast figures is nonsense. Nowhere near that amount is ever likely to change hands, and the EU needs a British financial settlement, if only because without it the alternative is worse: either cuts in EU budgets or bigger contributions from EU member-states, with both alternatives certain to unleash a political civil war inside Europe.

It is also implausible to claim - as European governments currently do - that no discussion on the future relationship between the EU and Britain is feasible until the Brits agree on the terms of the divorce; the reality is that the two dialogues will, by necessity, take place together.

And it is equally silly to argue that Britain's significant military and intelligence capabilities should not be used as a bargaining chip by London. For that is simply unrealistic; if the British cannot "cherry-pick" in the obligations they undertake to the EU, the Europeans can't cherry-pick the advantages they seek to derive from Britain either. And that's not a threat from London; it's simply a statement of fact.

Besides, it is clear that Britain's military and security importance is also one of the key dividing lines in Europe; the 12 member-states from Eastern Europe care more about this than almost anything else, and are not likely to wish to see Britain alienated. Either way, the idea that the Brits are mere beggars in this process remains simply untrue.

Still, the road which Mrs May has ahead of her remains strewn with political landmines. The first difficulty is sheer time and bureaucratic capabilities. An astounding total of 12,295 EU laws and regulations will have to be either negotiated, cancelled or amended. Hundreds of free trade agreements need to be concluded, all by a British civil service which until recently employed only 40 experts on trade.

And everything needs to be done in, effectively, just a year, since the negotiations proper may not start until after the German elections in September, and will require at least a further six months at the end for ratification by no fewer than 38 different national and regional legislatures.

DIALOGUE OF THE DEAF

Even worse is the fact that Mrs May has to negotiate not only with the EU; she also has to keep control over her own Conservative Party, which is split right down the middle between anti-EU Brexiters detesting any deal with Europe, and the so-called "Remainers", who hope there may be a way of keeping Britain in the EU after all.

The dispute between these camps destroyed the careers of three British prime ministers: Margaret Thatcher, John Major and David Cameron. Theresa May is determined not to become the fourth victim. But that won't be easy, for the debate about Europe in Britain is all about emotions rather than reason, and it's increasingly a dialogue of the deaf; as Mr Bruno Macaes, a Portuguese former Europe minister now settled in Britain, shrewdly remarked, the country's "Brexiters don't like the EU, while the Remainers don't understand it".

And if that's not enough, there is Scotland, where a nationalist regional government is determined to use Brexit as an opportunity to re-run a referendum on independence. Mrs May has rejected the idea of such a referendum before Britain is out of the EU and, at least for the moment, opinion polls back her decision, even in Scotland.

The British Premier's hope is that, as time goes by, the nationalists in Scotland will lose their popularity, and another referendum could be avoided altogether. But that is a high-risk approach, for any breakdown in the EU separation talks or any downturn in the economy could plunge Britain into a major constitutional crisis, and end up with the country's break-up.

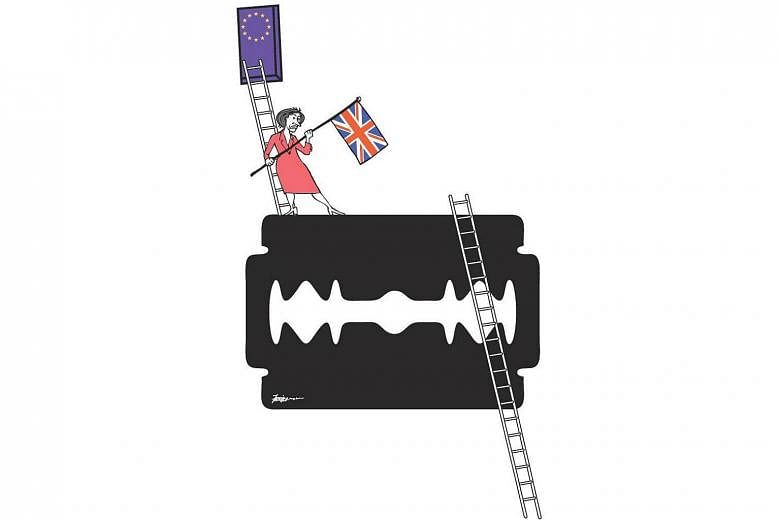

Mrs May faces the unenviable task of having to be flexible enough to get a deal from the EU, while appearing inflexible enough to avoid a rebellion within her party, and nimble enough to silence separatists at home and keep her country together.

It may work. But no wonder that, when informing MPs in London of the start of the negotiations, Mrs May echoed word-for-word an appeal by Winston Churchill, Britain's wartime leader and the last prime minister who succeeded in constructing that miraculous blend of vision, force and diplomacy.

Brexit, Mrs May told lawmakers, is one of those "great turning points in our national story". Mercifully, nobody asked her where she'd be heading after accomplishing that turn.